eBook - ePub

Using Students' Assessment Mistakes and Learning Deficits to Enhance Motivation and Learning

This is a test

- 162 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Using Students' Assessment Mistakes and Learning Deficits to Enhance Motivation and Learning

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Being wrong is an integral part of the assessment process, and understanding how to learn from those mistakes, errors, and misconceptions helps educators and students get the most from their learning experience. In this practical volume, James H. McMillan shows why being wrong (sometimes) is an essential part of effective learning and how it can be used by teachers to motivate students and help develop positive achievement-related dispositions. The six concise chapters of Using Students' Assessment Mistakes and Learning Deficits to Enhance Motivation and Learning show how mistakes affect students' engagement, self-regulation, and knowledge, and how teachers can most effectively contextualize supposed failures to help students grow.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Using Students' Assessment Mistakes and Learning Deficits to Enhance Motivation and Learning by James H. McMillan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Evaluation & Assessment in Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Better Being Wrong?

It has been said over and over—being wrong is an integral and necessary element of learning. Teachers and parents will contend that being wrong promotes learning; that it prepares students for the real world; and that it builds resilience, persistence, and resolve to keep trying in the face of setbacks, failures, and barriers. Some would contend that being wrong is just another opportunity to know what is correct—that it leads to innovation and invention. Famously, how many times did Thomas Edison fail before he discovered the right elements to invent the light bulb? He viewed being wrong as just another step toward being right. Being wrong also has implications from a broader perspective related to decision making. Obviously, people make wrong decisions, and hopefully learn from them. Indeed, it could be contended that it’s more important to make decisions right rather than make right decisions. When decisions are made right, we learn from them; we don’t look back and dwell on what could have been.

Of course, there are very costly mistakes or errors that are clearly undesirable, such as a pilot forgetting to put down the landing gear, a doctor operating on the wrong shoulder, an accountant making an error on a tax form, or a television presenter announcing that the wrong person won a contest (remember Miss Universe, 2015? On live TV, the presenter initially announced the wrong person as the winner!). In all areas of life, we make mistakes, sometimes big ones, so the issue is not about whether or not mistakes and being wrong occurs, but about how we are able to learn from our errors in decision making and performance to enhance our lives. This includes schooling and experiences students have with tests, papers, and other assessments of their learning. Is being wrong on school assignments and assessments promoted so that students benefit from knowing their mistakes, misunderstandings, and learning errors? My observation is generally not. The emphasis is on being right and showing proficiency, and being wrong may even be denigrated.

This book examines the dynamic of students’ performance on assessments in school, and being wrong in answering questions. Being wrong (sometimes) is described as a necessary element of schooling that promotes decision making that enhances, and indeed is essential for, effective learning and motivation. What is argued, based on research and theory summarized in Chapter 2, is that being incorrect and making mistakes on classroom assessments, at least sometimes, can be and should be enabling, not detrimental.

Clearly, we can learn from being wrong, even from something labeled a “failure,” or from what turns out to be a wrong decision about something, but is that what is happening in our classrooms (or at home)? Many would contend that, in reality, the dominant nature of what is communicated to students is the message that being wrong is a negative outcome that should be avoided. Each of us has experienced this, to some extent, first hand. For me, for example, an incident that occurred in a seventh-grade classroom still resonates. I was asked, in front of the class, to spell the word “ghost,” and I said “g-o-a-s-t.” I had obviously been taught phonetic spelling (perhaps to an unhealthy extreme). The reaction of the teacher was swift and demeaning. I was called out with something like “What (incredulously), you don’t know that ghost is spelled g-h-o-s-t?” as if I were unintelligent. Needless to say, especially because I was 14, I was thoroughly embarrassed. It was a very intense, painful experience. I was very dismayed; I learned that being wrong was bad.

Many contend that the idea that we embrace mistakes as part of learning, as an opportunity to grow and promote positive change, has been eroding (Berkun, 2011; Stevenson & Stigler, 1994; Tugend, 2011; Tavris & Aronson, 2008), replaced by a school culture that is addicted to the idea of success and being correct. Children are increasingly under pressure to be as “perfect” as possible (especially high achievers)—to get the highest ACT scores and best grades and take Advanced Placement and honors courses, all of which require being right, a lot if not all the time. As a result, being wrong is viewed as something negative, something to be avoided, and something to be blamed on someone or something else (Schulz, 2010). It has permeated schooling, especially in America. William Glasser’s influential best-selling book, Schools Without Failure, which was first published in 1969 and is still popular, espoused the benefits of a “success-oriented” school, one in which failure is absent. Along with decades of emphasis on behavioristic principles of positive reinforcement for success as the way to shape behavior, it is not surprising that in most schools, success and being right matters much more than risk taking that involves being wrong.

I’d like to share a vivid illustration of what we are facing. Megan Szabo is a middle school math teacher in Delaware (Delaware’s Teacher of the Year in 2015). She reported the following:

My students were doing online research about the design structure of skyscrapers. They were going to use this background information to design and construct their own skyscraper models out of spaghetti and tape…. Although they knew they were going to have to build a tower model, I had not told them what materials would be available to them, and they were getting frustrated. Unfortunately, this was not the first time my students practically begged me to give them an answer as soon as they started to feel frustrated. It was something that happened all the time…. Students have become so focused on getting the “right” answer that they do not care if it is spoon-fed to them by the teacher, even if that means they do not have to think for themselves.

(Szabo, 2015)

The prevailing message about being wrong is that poor performance means students are lazy, unmotivated, “dumb,” not capable, and foolish; being right means being responsible, motivated, focused, successful, and smart. The idea is that making errors and mistakes should be avoided because they are associated with the opposite of what is rewarded. The view is that being wrong is distasteful, unpleasant, and undesirable. This disparaging perspective, as it turns out, is deleterious, leading to all kinds of negative emotions and thinking. These are messages that I contend are misguided and harmful, for both high and low achievers. The real mistake, as pointed out by Schulz (2010), is that our culture is “wrong about being wrong” (p. 5).

An “anti-wrong/be-right” culture in schools mitigates the more positive ethos that making mistakes, or not being correct, is a signal for how to learn more and learn better. This anti-wrong culture is promoted in many ways through shared attitudes, values, norms, and behaviors. It is communicated to students by an emphasis on error-free performances, on rewarding very high levels of success (rather than rewarding risk-taking), on being right, and that getting a high score is what is important. “Success” to many students is only obtained by scoring 90% or more correct on a test, writing a “perfect paper,” or performing a skill flawlessly. When there is such pressure on students to not be wrong (especially some very high achievers)—that it is something negative—students employ maladaptive behaviors to avoid being wrong at all costs for fear of being criticized, judged, or embarrassed. This can result in both a serious “fear of failure” that prevents, rather than enhances, learning and student resistance to taking on challenging tasks and risk taking, resulting in negative associations with subjects being studied, stress, and anxiety (Tulis, 2013). Being wrong is clearly a negative in competitive classroom structures that distribute rewards on a normative basis (just ask a few very capable students who are in such classes with much higher-ability classmates). Fortunately, it is possible to turn “anti-wrong” assessment cultures into “pro-wrong” assessment cultures (more about this in Chapter 4).

Being Wrong and Assessment

The focus of this book is on how being wrong is manifest in the assessment process, and how it can be harnessed to improve learning and motivation. Indeed, I will make the argument that being wrong is essential for effective learning, as well as for the development of many positive traits and life skills, such as perseverance, resilience, risk taking, responsibility, self-regulation, problem solving, and a desire to enhance one’s competence. Because being wrong is so important, students deserve opportunities to make mistakes and errors and submit incomplete “correct” answers. I contend that we do a disservice to students if we do not purposefully integrate being wrong into how we teach and assess. Although these experiences occur to some extent in class discourse, including discussion, questioning, and seat assignments, it is clearly a factor in the assessments students take on a regular basis. Assessment is, in fact, a ubiquitous feature of schooling, taking up as much as a third of the time students spend in school throughout the year, and students answer questions correctly and incorrectly every week if not every day.

My argument about the positive impact of being wrong is based on a view of assessment that extends far beyond giving tests and grading papers. Assessment is a process that encompasses whatever strategies are employed to determine what students know, understand, and can do, as well as student and teacher perceptions about how assessment contributes (or doesn’t) to learning and motivation. Conceived in this way, assessment includes both summative assessment, such as end-of-learning tests and other tasks used primarily to document what students know, and embedded and more-formal formative assessment, which includes questioning, feedback, and instructional adjustments to help students close learning gaps. Just as important, assessment frames how the classroom and school culture influences what students are capable of, their current state of knowledge or skill, and how results from assessment can help learning. This could be thought of as an assessment environment or climate, and it is essential to how students perceive and use assessment information. What are the normative beliefs about what to do with assessment results? What attitudes do students and teachers have about learning from mistakes? Is assessment something that clearly promotes learning, or is it something that just documents it?

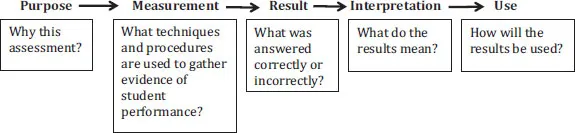

Figure 1.1 A Model of Assessment

An illustration of the student assessment process is shown in Figure 1.1. The five essential steps, implemented sequentially, are relevant to both teachers and students.

Purpose

In determining purpose there are many options, and often an assessment serves more than one purpose. The most important consideration is whether the purpose of the assessment is primarily summative or formative. I say “primarily” because some assessments serve both purposes. A summative assessment is used as an indication of what students know, their understanding, or their level of skill (not necessarily what they have learned). This essentially is what is done with most tests, quizzes, and papers. The purpose of formative assessment is to enhance student learning. Although gathering performance information is needed for formative assessment, the emphasis is on helping students progress toward greater proficiency. As you are probably well aware, formative assessment is receiving more and more emphasis, and this hopefully will contribute to a more positive attitude about how being wrong can promote learning since it is typically not graded.

Beyond this essential difference in how assessments are used, either of learning or for learning, there are a number of other possible purposes, each of which will also have implications for being wrong:

- Is the purpose to show students how they compare with other students (norm-referenced) or how their performance aligns with established criteria or standards?

- Is the purpose to use test scores to determine grades?

- Is the purpose to give students feedback about their progress?

- Is the purpose to motivate and engage students? To challenge them?

- Is the purpose to develop life skills such as responsibility, resilience, and self-regulation?

- Is the purpose to predict how students will perform on an end-of-year accountability test?

- Is the purpose to gather data that will be used to evaluate the teacher?

The main purposes of assessment communicate the reason for assessment and why assessments are conducted. This in turn influences the beliefs students have about the goals of assessments, and these beliefs are just as important as those of teachers, administrators, and parents. Recent research on student perceptions of assessment shows that students discern differences between varied purposes of assessment. Brown and his colleagues (Brown, 2008; Brown, 2011; Brown & Harris, 2012; Brown & Harris, 2013; McInerney, Brown, & Liem, 2009), in a series of studies, found that student conceptions of assessment consist of four main components: (1) assessments for school, teacher, or student accountability; (2) assessments to improve teaching and learning; (3) assessments to establish the relevance to learning; and (4) assessment that provides a useful description of performance. Each of these was scaled (e.g., relevance ranged from helpful to learning to irrelevant), so that perceptions ranged from being more or less positive or intense. Think about how these conceptions could affect students. When students see assessment as being unconnected to their learning, they are probably less inclined to be meaningfully engaged in either learning or the assessment. Effort is likely to be stronger for assessments that provide helpful information to improve their learning. This line of research suggests that, from the beginning, students pay attention to the purpose of the assessment, and react accordingly. When assessments are viewed as being positive and supportive of learning, challenge, effort, and how one performs have greater significance. Being wrong, likewise, has greater significance. Being wrong on irrelevant assessments will mean much less than when mistakes and errors are made on assessments that are crafted to motivate and provide helpful feedback about how to improve.

Measurement

Once the purposes have been determined, assessment techniques that align with the purposes are identified and used to generate scores or grades. For example, if the purpose is summative, focused on what students know about history or science, a selected-response-item type of test, such as one using multiple-choice and matching questions, may be most appropriate. This type of test allows for a broad sampling of content when the emphasis is on recognition, definitions, and memorization of facts. If students are learning a skill, such as how to use a microscope, give a speech, or repair a motor, a performance assessment is probably better than a test. If the purpose is to engage students in deep learning and thinking, some kind of constructed-response assessment, such as an essay, project, or paper, is more appropriate than a selected-response set of items on a test. If one purpose is to challenge students, careful attention needs to be given to making the assessment at the right level of difficulty. This is difficult in classes that contain students with different levels of prior knowledge and ability. The same assessment can be overly difficult for some students and very easy for others, mitigating the right level of challenge needed for both groups. If a purpose is to teach students self-regulation, self-assessments and reflections are effective.

Result

Results can be reported in a variety of ways. The total number of points earned for each question can be summed and compared to the total number of possible points. Points can be c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Better Being Wrong?

- 2 Why Being Wrong (Sometimes) Is Better: The Science Behind It

- 3 Students’ Perspectives About Being Wrong

- 4 A Positive Being-Wrong (Sometimes) Classroom Assessment Climate

- 5 Assessment Practices That Promote Being Wrong (Sometimes)

- 6 Effective Feedback When Students Are Wrong

- Index