[T]hose various types of distributed memories [collective memory, communicative memory, and cultural memory] reinforce the concept of memory as shared process, as a condition that takes us out of our immediate reality and allows for an awareness of connections and contingencies. Public memory resides precisely in that transitional realm of individual awareness and collectively scripted narrative of self-expression and context. To activate public memory, that is to render it an agent of the moment. We need to work in that ambiguous realm and to bring our audiences to it.

Carin Kuoni, Creative Time Summit: Revolutions in Public Practice, 2009

We shaped the Summit in order to uplift political art and to make the case for its relevance to the community of artists, scholars, and cultural workers that form not only the art world but also the world beyond. We, at Creative Time, wanted the Summit to introduce audiences to the vast world of political art production and to make a case for the power of art to transform society. That said, the first important task was to make the case to the art world itself.

The methodology and content of the Summit built upon a number of important precursors. One of the more significant conferences in New York history that guided our vision for the Summit was the Town Hall series at the DIA Art Foundation that took place in 1980. The first half of the project consisted of an installation by Martha Rosler titled If You Lived Here, which responded to questions of gentrification and housing. The second discursive exhibition and platform was by the collective Group Material, titled Democracy. Both featured a series of conversations on topics that would not only continue to be urgent at the time of the first Summit—including gentrification, intersections of class, race, and cultural production, AIDS activism, and strategies to resist capitalism—but also put forth a politically progressive agenda by way of an art institution.

In addition to these seminal projects at DIA, we at Creative Time (which, most importantly, included then Executive Director Anne Pasternak) found inspiration in the work of Okwui Enwezor, the artistic director of documenta 11. The 2002 edition highlighted art from the global South and brought colonialism front and center as an important rupture in the production of culture. In addition, Enwezor produced a series of discursive “platforms” that emerged in major port cities across the globe. These platforms, as they were called, featured philosophical and political voices from across the cultural spectrum. Urgent and necessary conversations on subjects ranging from truth and reconciliation in South Africa, to the concept of creolization, to the rise of neoliberalism were being addressed by the world’s sharpest minds. And what else could bring them together than art itself? It was within the field of art where these conversations that seemed both urgent and, strangely, beyond the bounds of contemporary political discourse could emerge.

It is also helpful to note that Creative Time itself had a history of organizing around art and politics. In 2006, Creative Time organized three roundtable dinners asking artists, curators, and academics about the state of art and politics. Many of these artists would continue to play a role in Summits to come, including Doug Ashford, Julie Ault, Hans Haacke, Emily Jacir, Lucy Lippard, Daniel Martinez, Marlene McCarty, Helen Molesworth, Anne Pasternak, Paul Pfeiffer, Michael Rakowitz, Martha Rosler, Ralph Rugoff, Amy Sillman, Allison Smith, Kiki Smith, and David Levi Strauss.

Just a year previous to the first Summit in 2009, Creative Time organized a large-scale project at the Park Avenue Armory titled Democracy in America: The National Campaign. It could be considered, in some manner, a test case for what would become the Summit. With its cavernous hall, the Armony was transformed into an ad hoc hub for social politics, which brought together voices ranging from David Harvey to the Guerrilla Girls, the Yes Men, Critical Art Ensemble, Brian Holmes, and Karen Finlay, among others. As part of Democracy in America, curator Daniel Tucker and I went to five cities—New York, Baltimore, Los Angeles, New Orleans, and Chicago—to initiate in-depth conversations with artists and activists. It became evident, in 2008, that, rather than only fighting the Bush administration’s role in Iraq or the Patriot Act, an issue that evidently had captured the imagination and work of many artists was a topic that would come to be a critical part of the Summits for the decade to come: gentrification.

The Summit also emerged out of a recognition of an ever shifting vast landscape of political art. The broad array of approaches provided an opportunity for a conference where these regional and aesthetic specificities could be explored, from the community-based work of Appalshop in Appalachia to the social practice art coming out of Portland and San Francisco, to the politically engaged social practice out of Chicago in spaces like Mess Hall, to the discursively rigorous work inspired by or in connection with the Whitney Independent Study Program in New York City. More directly activist work like the agitprop activities of the Guerrilla Girls or the Yes Men expanded this landscape even further. And that was just in the United States.

Admittedly, our knowledge of art making outside of our immediate, United States–based context would take some time to come into sharper relief. We began by highlighting the work of cultural workers and artists already familiar to us: the work of curators such as Lars Bang Larsen, Okwui Enwezor, Chus Martinez, Maria Lind, Bisi Silva, Gridthiya Gaweewong, and the Croatian collective What, How and for Whom, as well as the work of artists such as Dinh Q. Le (Vietnam), Etcétera (Argentina), Regina José Galindo (Guatemala), Chto Delat? (Russia), Minerva Cuevas (Mexico), and Yael Bartana (Israel). Many of these artists and curators are well-known in the arts circuits of biennales, major exhibitions, and art fairs. The Summit’s network of international artists would expand over time as we continued to have conversations and grew our network and knowledge of practitioners.

Presenter Okwui Enwezor at the first Creative Time Summit: Revolutions in Public Practice, 2009.

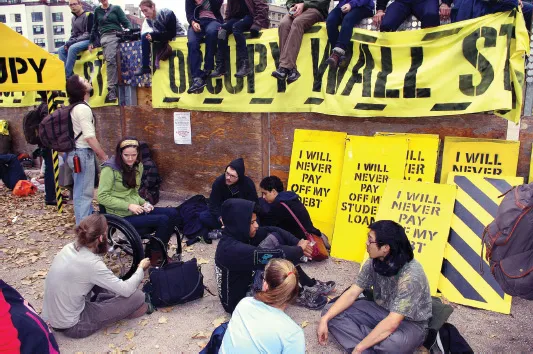

The first Creative Time Summit took place in 2009, one year into the Barack Obama presidency, and in partnership with the New York Public Library. It was seemingly the dawn of a new era. Eight years of George W. Bush as president and the so-called War on Terror had somewhat come to a close; the country had clawed its way out of the big bank bailout of the subprime mortgage crisis. Obama rode into office with promises of closing Guantanamo Bay, and, after eight years of Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney, the new presidency sent an electric shock that history was in the making.

The 2009 and 2010 Summits made a case for political art. We aimed to acknowledge its history and to make space for those artists and collectives that possessed active disdain for the mainstream art world and capitalism in general. Established contemporary global curators and artists such as Okwui Enwezor, Maria Lind, Thomas Hirschhorn, Carin Kuoni, and Alfredo Jaar presented alongside historically important art activists and social practice creators such as Gregory Sholette, Suzanne Lacy, Harrell Fletcher, and Mel Chin and off-the-circuit contemporary activists such as Baltimore Development Cooperative. This would be an evolving formula that would become more global and interdisciplinary as time went on

Leveraging the social capital available from established artists and curators, we put forth a platform that was consciously resistant to power. We were cognizant of the world of conferences that were beginning to emerge in the media landscape. The dot-com–supporting blockbuster innovator conference TED haunted us with its flashy motivational speeches, solid embrace of popular education, and adoration for the rising world of technology. We wanted to keep the conference grounded by speaking truth to power and to simultaneously play a spotlight on many projects that remained hidden. In doing so, we walked the tightrope in the inevitable contradiction of being a resistant program at the center of global capitalism. This contradiction would become more apparent in years to come.