Beijing via Wellington (via Shanghai, Berlin, Vancouver … )

In 2004, Yin Xiuzhen showed her Portable Cities project in the exhibition Concrete Horizons: Contemporary Art from China, held at the Adam Art Gallery in Wellington, New Zealand. Portable Cities is a mutable artwork consisting of variable numbers of ‘suitcase cityscapes’, each fabricate d from used clothing, found objects and maps taken from a particular urban centre. Between 2000 and 2004, these cityscapes were installed in differing configurations, usually in combination with local sound recordings, in galleries and exhibition spaces throughout the world. The suitcase cityscapes installed in each show varied, but the roll call of cities mapped by the project as a whole reads like a list of the metropolitan centres that rose to international artworld prominence during the 1990s – Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Lhasa, Singapore, Lisbon, Berlin, Sydney, Vancouver, San Francisco, Minneapolis – and to these were added, in Yin’s work, well-established centres such as New York and Paris.

This obvious ‘name check’ demonstrates more than Yin’s extraordinary success as an individual artist,1 it signals the accelerated international profile of contemporary art from China in the years following the 1989 protests in Tiananmen Square and the country’s subsequent ‘open’ cultural policy and engagement with global trade networks. Chinese art is, arguably, the art market success story of the past 15 years – indeed, Charles Saatchi’s recent

decision to focus his new gallery around a collection of contemporary art from China is clear confirmation of the market dominance of the work.2 Similarly, China itself, in terms of the global marketplace, is a tiger rising from its rest; the massive infrastructural work being undertaken in Beijing, Shanghai and other metropolitan centres is but a small measure of the changes being wrought to the country as a whole as it becomes a truly global economic force.

Portable Cities can lend itself almost too readily to these dual frameworks, attesting to the art market’s ability to make international superstars of young artists from China, who spend their time travelling from one biennale to another, their works and lives packed into suitcases and carried on long-haul flights. The world-traveller contemsporary Chinese artist tirelessly reproduces the cities she sees, each becoming more like the other, more an interchangeable image packed in a case than a lived space, as the pace of globalisationirons out the last individual wrinkles left to suggest that cultural difference might be anything more than the consumable pleasure of the exotic.

I would contest this rather obvious, clichéd reading of Portable Cities, however, and, indeed, criticism of Yin’s work that simply locates her as an ‘authentic’ Chinese woman artist longing for the return of her home, Beijing, to an imaginary past beyond the reach of change or the introduction of ‘foreign’ influences. By contrast, I would argue that Portable Cities demonstrates, materially, how a contemporary woman artist from Beijing makes herself ‘at home everywhere’.

The urban skylines of Portable Cities are, literally, supported by suitcases [colour plate 4]. In this sense, the works convey immediately an important paradox: the cities’ iconic profiles can be identified by seemingly fixed symbols (the Golden Gate Bridge, the Eiffel Tower, etc.), yet their foundation, the ground on which they rest, is quintessentially mobile and dynamic, produced as it is from well-travelled luggage. There is a fascinating parallel between this paradox, one that I would argue is central to Portable Cities, and the insights of geographers such as Saskia Sassen, who have sought to understand the significance of metropolitan centres to the phenomenon of globalisation. As Sassen has argued, the inter-state system that dominated world-wide exchange over the past three centuries has now given way to a transnational economy that operates through key metropolitan sites. These metropoles simultaneously centralise resources (producing ostensibly stable urban points) and increase dispersal, fluidity and movement by facilitating and extending transnational interchange.3

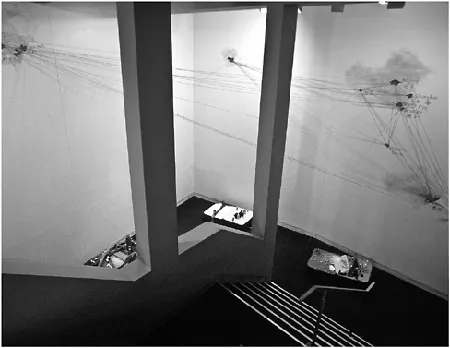

Yin’s cities operate likewise, allowing us to capture the ‘essence’ of these urban sites, fix them in our imaginations, yet be aware of their movement, their likelihood to be folded away at any minute and transported to the next space. There is a tension produced in every installation of Portable Cities between the specific materiality of the places enfolded in the suitcases, their skylines fashioned from the used clothes of their inhabitants, and their interaction in the space of the gallery as nodal points, linked by a creative cartography drawn differently in each show. The cities in which viewers stand participate in an aesthetic map, making connections between and across art, culture, economic exchange and the contemporary geo-political terrain of globalisation. ‘Beijing’ is understood simultaneously as an entity in itself and within a fluid pattern of movement and exchange: via Vancouver, New York, and so on.

In this sense, Yin’s project again parallels Sassen’s insights and extends the implications suggested by other geographers who have focused on global cities networks. For instance, understanding contemporary metropolitan centres as ‘portable cities’ has profound implications for unpicking what Peter Taylor, David Walker and John Beaverstock called ‘embedded statism’, the epistemological legacy of the primacy that European nation-states have enjoyed from the middle of the 18th century until quite recently. Through a detailed materialist analysis of the emergence and development of world cities in globalisation, they have provided compelling evidence for their claim that it is not only possible, but necessary, to ‘juxtapose [an] alternative metageography of a network of world cities – a space of flows – against the dominant, conventional metageography of nation-states – a space of territories’.4 Like Sassen, Taylor et al. have argued for a change in the foundation of our geographical imagination. Rather than understand the world as a set of bounded nation-states, we need to engage productively with the geographies of transnational exchange, located in very material ways, through multiply interconnected urban centres, or, as I am suggesting in keeping with this reconfigured founding frame, through a creative map of portable cities.5

The ramifications of re-orienting our geographical imagination are extensive, and this chapter will certainly not exhaust them. Crucial to the present argument are two main points: first, that the ‘alternative metageography’ that is being developed here does not simply reverse the existing binary logic that pits territory/stability against flows/rootlessness; and second, that the founding relationship between home and identity can be rethought through concepts of movement to productive ends. The first point has an impact upon the development of a cosmopolitan imaginary that is relevant to the present geo-political climate as well as materially connected to contemporary art practices, while the latter enables an argument to be made that connects the agency of art-making with the articulation of identities-in-process. I see the two as intrinsically linked.

Critically analysing the concept of home is imperative to making this connection, and my argument is indebted to the numerous scholars from widely differing disciplines whose work has sought to rethink ‘home’ as both a conceptual and material formation. Crucial to this is the question of movement or, as the editors of Uprootings/Regroundings: Questions of Home and Migration put it: ‘(b)eing grounded is not necessarily about being fixed; being mobile is not necessarily about being detached’.6 The necessity for stating this remains with us, despite decades of post-colonial research on exile, migrancy, and transnational and global exchange. The necessity is predicated upon the strength of the hold exercised by a geographical imaginary that equates home with stasis, stability and security (in terms of both safety and secured identities) and exile/migrancy with detachment and rootlessness – the loss of an authentic and sustained origin point. It will suffice to remind ourselves that this logic underpinned some of the most brutal activities in living memory, from the attempted genocide of the ‘rootless cosmopolitan’ Jews in Europe at the mid-point of the 20th century, to the present refusal of sanctuary to tens of thousands of refugees throughout the world.

There have been many astute analyses of the reactionary tendency to equate domesticity, as both home and nation (‘domestic’ as opposed to ‘foreign’), with security, and to guard its boundaries jealously against vilified others, not least among feminist scholars aware that the domestic sphere is not always the safe haven for women that such myths maintain. Indeed, feminists have long critiqued the simplistic equation of home with identity and community as too fixed, too brutally defended and too undifferentiated.7 As a foundational myth, however, it is not easy to supplant.

Portable Cities provides a space in which we might begin to unravel the potent oppositions between home and away, stability and exile, authenticity and rootlessness, that make it so difficult to develop new ways of thinking through the mobility of subjects, identities and community as they are now experienced so commonly throughout the world. Crucially, Portable Cities suggests a modulation between objects and processes – between the metropolitan centres it materialises and the flows and networks they engender. Using this modulation, the installation of the suitcase cityscapes maintains a productive tension between the local and the global, the concrete and the conceptual. In engaging with the work, we are able to see that the soft urban silhouettes are fashioned from clothes – clothes taken from the cities’ own residents. As we remember or imagine these iconic skylines, we are invited to step back, to read the suitcase cities installed here as a map, and to make connections between the intimate, portable places at a macropolitical level. The work never collapses one into the other, but rather, like stars in a constellation, the cityscapes retain their particularity while at the same time becoming more than themselves through their vital, global, interconnection.

As a way of imagining urban domesticity both as a local, materially specific phenomenon, and as one that is wholly embedded within dynamic world networks, the work counters a significant and fundamental assumption – that the strength of our homes, our nations and our identities rests on our ability to provide unyielding foundations. But the development of a contemporary cosmopolitan imaginary, of truly connected world citizenship in a era marked by global cities networks, suggests the establishment of a new founding logic, one capable of acknowledging the intimate interaction between the local and the global, the domestic and its ‘others’. In Portable Cities, Yin’s home is still Beijing, but this is Beijing via Shanghai, Singapore, Berlin – a truly global home.8

In configuring a multi-centred, global home, Yin is in good company. For example, arguing against the anthropological conventions that take home to be the fixed locus of identity and community, social theorists Nigel Rapport and Andrew Dawson wrote: ‘a far more mobile conception of home should come to the fore, as something “plurilocal”, something to be taken along whenever one decamps’.9 The resonance of their argument with Portable Cities is as striking as it is intriguing. If, as I would argue, Portable Cities enables Yin to make herself at home everywhere, or at least in every metropolitan centre she negotiates as a successful contemporary artist, then the work can indeed be seen as a ‘plurilocal’ home taken along whenever she decamps. I am not suggesting, however, that Portable Cities is merely an illustration of social theory, the depiction of a more mobile conception of home. Rather, I am arguing that contemporary art can provide a distinctive perspective on the core cultural, intellectual and political debates of our time, in this instance offering a means by which we might participate in the imaginative spaces that emerge as movement and process become fundamental to notions of home, identity and community. The paradigm shift Rapport and Dawson called for as a matter of priority within the social sciences is materialised here in art; each tells us something about the need, and the potential, to create new ‘founding’ figures appropriate to the dynamic geo-political circumstances of globalisation.

Returning to the material qualities of Portable Cities is useful here. The cityscapes might be described as works of reclamation, in which discarded domestic materials are transformed into iconic urban images for a global art audience. These works of art reclaim the quotidian as a powerful signifier within the processes of globalisation, processes commonly assumed to destroy local, everyday differences in their quest to produce a uniform world market. Commenting on the qualities of the everyday in Portable Cities, the critic Melanie Swalwell argued convincingly that the project does not so much represent displacement, all too commonly cited as the principal experience of globalisation, but registers the activity of emplacement, of making place within a rapidly moving and fluid network of exchange.10 This thinking parallels my own, and demonstrates a powerful riposte to many of the most intransigent assumptions concerning the impact of globalisation on the concept of home, not least the assumption that the local and the global, the domestic and the foreign, are antagonistic opponents rather than, as I would argue, intimate interlocutors.

Critical to my argument here is the link between the fabric of the works and their fabrication; it is my contention that the materiality of the suitcase cityscapes, the processes of their production and the locus of their consumption (as art works specifically designed to be seen in multiple, metropolitan sites), are integrally connected. This integral link establishes them firmly within the dynamics of globalised world cities networks, yet at the same time capable of effecting a critical dialogue with and through the local. Yin’s material focus on the fragile remnants of everyday lives, lived, makes Portable Cities more than a monument to the memories of the cities’ inhabitants. The clothes and cases provide the ground from which Yin makes herself at home everywhere; through manifold acts of domestic reclamation, we are invited to imagine and make our homes in the world anew.

Understanding Yin’s Portable Cities as a multiple act of making – making art, making home, making subjects – reiterates the figure of foundation as a practice, an act of establishing, settling or introducing something new. As an act of foundation, Portable Cities connects the affective qualities of home with the material qualities of contemporary art; this in turn enables individual subjects to connect with collective forms of cultural signification. The quotidian elements of Yin’s work are profound precisely because they link the most ordinary individual activities of living in a city – wearing, tearing, mending, walking, carrying – with the collective bodily engagement that produces the image of the global city itself, its ‘visage’ or skyline. The everyday movement of pe...