This is a test

- 136 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A wide-ranging issue of the UK's leading socialist feminist journal including articles on motherhood, disabillity and women and modernism.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Feminist Review by The Feminist Review Collective in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Feminismo y teoría feminista. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Reviews

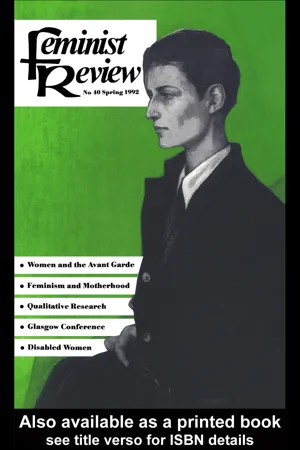

Feminist Review No 40, Spring 1992

Armed Angels: Women in Iran

Mandana Hendessi, CHANGE, (International Reports, No. 16): London, 1990 £2.30 Pbk

Armed Angels: Women in Iran is a detailed historical analysis of women’s position in Iranian society from 1850– 1990.

Mandana looks at women’s position in three separate and yet related periods. First, she examines the deep-rooted patriarchal relations in Iranian society between 1850 to the beginning of the Pahlavi dynasty, 1926. She argues that, prior to Islam, the male-dominated nature of society ensured that women exercised little control over their lives. She suggests that Iranian women’s oppression, and consequently their veiling, was largely due to prevailing social conditions rather than the moral teachings of the Koran.

Focusing on the period between 1926– 1978, under the Pahlavi regime, she looks at worldwide socioeconomic changes and their impact on Iranian society, particularly issues concerning women’s place in the family and workplace. The third section is devoted to an analysis of women’s position within radical Islam generated by Shariati, as well as women’s practical experiences under Khomeini and the post-Khomeini era.

The strength of her pamphlet is the way in which she attempts to provide comprehensive historical evidence of Iranian women’s sub-ordination, rather than the more narrow approach of looking at Islam as the main cause of women’s oppression. However, we should not overlook the importance of the role played by Islam in perpetuating and strengthening women’s subordination in all aspects of life, at all times. Furthermore, to suggest, as Mandana does, that ‘women’s seclusion was not ordained by Islam’, is overly general and brief. To argue the case successfully, she needs to provide historical evidence about the conditions that led to women’s oppression in the pre-Islamic period, and more detail about the specific forms that this oppression took. By looking at the period from 1850–1990, one cannot say anything about the pre-Islamic period.

Throughout, Mandana provides historical events to show how the unity between Islamic institutions and ruling bodies has always managed to ensure that women are kept under control. Also, she demonstrates how women’s active participation in, and mobilization for, politics has been motivated in order to defend the ‘nation’, and to make it possible for them to perform their ‘patriotic duty’ without any political gains and rewards as women.

By looking at major events such as the Tobacco Crisis of 1891–92 and the constitutional revolution of 1905–11, she explains how increased Western penetration of Iranian society led to the development of Western Victorian models of life. Women’s activity during the Tobacco Crisis, and their part in the constitutional revolution, was highly significant and impressive. Unfortunately, they fought for a constitution which stated that only men had the right to vote and be elected.

The Pahlavi era was one of rapid modernization and industrialization that affected the whole structure of society. Women were encouraged towards further education and a higher degree of public participation. The price of these gains, however, was paid for by women ruthlessly being forced to unveil and dress in accordance with state policies. To placate the Ulama, Reza Shah made sure that women were kept inferior by incorporating part of shari’a into the new body of Iranian civil law. Under this law, a man could divorce his wife when he pleased, while a woman could divorce only on specific grounds such as impotence and infidelity. Also, women’s inheritance rights were less than those of men. The husband was constituted as the head of the family with legal control over the children. Most importantly, women were not able to vote or stand as candidates in election to the Mazlis (parliament).

The centralization of political power resulted in the rigid control of women’s employment, education and clothing. The counterforce to these repressive measures took different forms. However, it was really only during the 1940s that women’s political organizations, which had been suppressed for so long, began to emerge. Women’s active participation during the nationalist insurgency, led by the Democratic organization of Iranian Women (DOIW), mobilized masses of veiled, as well as unveiled, women. Once again their demands around economic independence, state welfare for poor women and children, equality of men and women, review of the marriage law, wage equality, and maternity leave for all women workers (including domestic workers), took second place to the proposals of the nationalist leadership which included some of the Ulama.

The crushing of the nationalist movement by the Shah (backed by Britain and the United States), meant further suppression of all the opposition organizations. Armed Angels looks at the political, social and economic implications of the Shah’s ‘white revolution’, and the effect of the quadrupling of oil prices on the lives of Iranian women.

Mandana’s analysis of women’s resistance and opposition contains certain weaknesses. Although the impact of socio-economic circumstances is discussed in detail, very little is said in a systematic way about the political and organizational forms of women’s struggle during the ninety years of successive governments.

She refers to the existence of women’s independent organizations which were crushed by 1930, but does not explain what this tradition was and which organizations she is referring to. A more complete picture of this would require a discussion of the aims and objectives of the forms of their resistance, their weaknesses and strengths. She could also have discussed what the aims and objectives of the following organizations were: The Society of Masked Women (Arjuman-i zanans Negabpush, 1911); Patriotic Women (Nesvan-i vatkanha, 1922); Messengers of Happiness (Pazk-i Saadat, 1922); Association of Women’s Revolution (Mazma’eh Ingilabe Zanan, 1922); Awakening of Tehran Women (Bidari-yi Nesvan-i Tehran, 1926).

The lack of systematic analysis of the women’s movement allows her to overlook the importance of the role that could have been played by the left, both before and during the 1979 revolution. She refers only to the left’s ambiguous and unspecific position on the question of women.

Without looking in detail at women’s theoretical and practical experiences, it is not possible to provide a precise account of the conditions which left them unarmed, isolated and easy targets to crush. Unfortunately, in most cases the left organizations either believed there was no ‘women’s question’ at all, or their support for women’s equality and emancipation was there mainly to recruit more women.

In the final section, Mandana looks at the conditions of women within radical Islam and under Khomeini’s rule, and explains how the idea of armed angels became a revolutionary theory. Before going further, it is important to look at her definition of ‘armed angels’. In the introduction she suggests the contradictory policy changes concerning women for the last ninety years: ‘Through veiling and secluded existence within the andarunn (innercourtyard), to taking militant part in revolution, from being forced to unveil and then reveil themselves, sent into an exploitative market place and later back to the confines of domestic life in the interest of the state, the dichotomy of the armed angel emerged.’ It is important to be clear that when Mandana refers to women’s secluded existence through veiling and to their existence within the andarunn, she refers to the condition of a minority of women in nineteenth-century Iran. As she says, during the 1850s, over 80 per cent of the population lived in the countryside and obviously had a different life from the urban 20 per cent. There is no evidence of women’s seclusion in the countryside, not because they were emancipated, but because of extreme poverty and their high degree of economic activity within agricultural industries.

Another statement, which describes women’s conditions in the twentieth century, reads as if the emergent dichotomy of the ‘armed angel’ is a description of the conditions of Iranian women within capitalism. Women, whether in developed industrial capitalist societies or in less developed ones, have always been used as instruments of state policies, despite the fact that their oppression may take different forms in relation to specific, social conditions. Women have always been encouraged to be caring angels, and, if necessary, public participants in social affairs. In Iran the instrumental position took a radical form because extreme conditions necessitated extreme measures.

The idea of the armed-angel-as-revolutionary simply explains women’s condition within radical Islam and not in Iran. As Shariati advocates, and Mandana refers to: ‘The comparison was made with the two Moslem heroines of the past—the armed ones and the angel Zeinub and Fatima—by Ali-Shariati who transformed these symbols of suffering and helplessness in the hostile world into active revolutionaries who fought for social justice.’ It is within radical Islam that women are encouraged to be devoted wives and selfless mothers, while at the same time expected to take up arms and get directly involved in political life. Therefore, the name of Mandana’s booklet is not appropriate as a description of the condition of Iranian women in general.

Finally, Mandana looks at the dual responsibilities of Iranian women which are guaranteed by the principle of Velazat-e-Fagih. She discusses the role played by women during the Gulf War where they have been used to serve the war industries in paid and unpaid labour, and have been instruments of propaganda for the regime, portrayed as symbols of devotion and sacrifice. This, in fact, has been used to challenge those critical of the Islamic regime.

Women’s condition within the family is also discussed as a means of controlling their social and sexual behaviour. Mandana argues that the implication of Muta (temporary marriage) and the function of Bonzade-e-Ezdevag (foundation of marriage) are critically important in understanding the forms of sexuality imposed on women. She explores the implications of all forms of law as part of the government’s systematic attack on women’s rights.

She concludes by arguing that despite the absolute deterioration of their legal and social rights, women are seen and recognized as too important socially and economically to be ignored; yet the burden of being the domestic worker, selfless worker and devoted wife is the reality of women’s life in Iran today. She believes that: ‘unless women reject the enforced ideology of armed angel and take full control over their lives, they will never be fully emancipated’.

I would like to add that the precondition for women’s emancipation is not only the rejection of the ideology of armed angel, but also the demand for a new division of labour and the responsibilities of childcare, the disappearance of all forms of actual and assumed dependence on the male wage, and the transformation of the ideology of gender and sexuality.

Armed Angels is full of substantial and stimulating material. It covers the most dynamic period of Iranian history. I finished it feeling that such an informative piece of work has been long overdue. I recommend the work to anyone interested in knowing about the past and present conditions of Iranian women.

Elham

Note

Armed Angels is available from CHANGE, P.O. Box 824, London SE24 9JS. Telephone: 071 277 6187

Seductions: Studies in Reading and Culture

Jane Miller, Virago: London, 1990 ISBN 0 86068 943 3, £14.99 Pbk

Kate Millett’s broadside against Normal Mailer, Henry Miller, and other gurus of twentieth-century sexual and political radicalism and flagrant traducers of women gave us, in Sexual Politics, one of the founding texts of feminism’s ‘second wave’. Subsequent Anglo-American literary criticism preferred to recover and study women’s writing. Jane Miller’s Seductions returns the spotlight on to another kind of male-authored text: works of theory in which women are not so much traduced as ignored: four key writers whose work has profoundly affected the development of twentieth-century cultural studies: Antonio Gramsci, Raymond Williams, Edward Said and Mikhail Bakhtin.

We might, of course, return the compliment and ignore what radical feminism has termed ‘malestream theory’; but not without loss. Miller’s strategy is rather to engage with these writers, countering them not, or not only, in their own terms but by drawing on less abstract forms of writing which have sometimes been claimed for women and feminism: fiction, biography, personal writing.

Seductions, as befits its title, is engaging, subtle, charming, disarming— a good read. It progresses not in a straight line dictated by an argument, but laterally, with loups and detours. We are treated, for example, within the confines of a chapter whose main theme is the significance of Gramsci’s concept of hegemony, to a comparison between two eighteenth-century literary seducers: Richardson’s Lovelace and Jane Austen’s Willoughby. We are given snippets of autobiography as Jane Miller reflects on her own experience as a student at Cambridge, a young mother, a niece. And at the centre of her book we have the figure of her great-aunt Clara Collet, who was not the prototype for Gissings formidable ‘new woman’ Rhoda Nunn, but was certainly her equal and her likeness. She was a civil servant in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, living like a man in chambers, and, like her literary counterpart, with more than a hint of austere masculinity about her.

The features of the terrain explored by the book are made visible through the guiding metaphor of seduction. Seduction rather than hegemony is chosen to characterize women’s relationship to cultures that both include and simultaneously exclude us. Miller’s argument is that we are seduced into ambivalent assent to our own domination through myriad temptations. Any one of them may be resisted; but ultimately we merely choose between them.

Women in patriarchal capitalism are, in Gramsci’s term, subaltern: inferior: of subordinate rank; but also, in the context of logical categories, particular rather than general or universal. But abstract theorizing refuses particularity in a ‘lofty…tradition of philosopher kings… for whom the sexlessness of important ideas and of thought itself is axiomatic, and whose style expresses only genial disapproval of an attention to differences between women and men.’ (4) Subaltern woman cannot escape her sex, her particularity; hegemonic man is unable or unwilling to see himself and his theory as gendered.

So, Miller proceeds by teasing out gender-absences (and equally telling presences) as metaphor. Thus on Said: ‘Within these anti-imperialist discourses it is women’s vulnerabilities and the injuries they attract to themselves which become metaphors for the injuries suffered by whole societies and for the consequent humiliations of their men’ (120), in the work of these theorists. But she counterposes them not with critique, modification, reworking: the work of feminist theorizing; but with women’s words in other, more particularizing forms of writing: Gramsci’s hegemony is set alongside narratives of seduction and betrayal; Williams’s working-class male romance with Carolyn Steedman’s biographical and autobiographical landscape; Said’s metaphor of colonial feminization with Toni Morrison’s Beloved; Bakhtin’s Rabbelasian carnival with Margaret Atwood’s Cat’s Eye, and the hesitations of a young black A-level student in the face of the demands of a syllabus and a way of reading which excludes her experience; and at the centre, with a woman’s life.

Miller makes the metaphor go a long way, and she uses it to make some telling points. Yet like all metaphors it may be pushed too far. Used to stand for the form of women’s incorporation into the gendered mainstream of social life it is not quite right. For this is a stepping into femininity, into all-too licit heterosexual marriage. But she who allows herself to be seduced steps outside the bounds of propriety, to partake of illicit pleasures— to yield, deliciously, recklessly, to temptation.

Seduction bespeaks transgression, and Miller’s main use of the term is to characterize feminists’ relationship to transgressive theories aimed at laying bare modes of cultural domination. Miller writes of such theorizing as ‘perhaps one of the deadliest and least resistable of seductions for feminists’ (8).

These are strong words. Yet there is something not quite right here either. To be seduced is to succumb to overwhelming temptation against one’s better judgement. It implies an active if duplicitous wooing. Yet our plaint was of neglect. It is feminism, therefore, that must take the active part in forging any relationships with these theories, determining the terms on which they are entered. Feminists who have drawn on them may rightly want to object to a metaphor which suggests an unprincipled, total, and passive mental yielding. If we have been seduced, then this must be shown through analysis of the uses made of those theories by feminists.

Terry Lovell

Heroes of Their Own Lives: The Politics and History of Family Violence

Linda Gordon, Virago: London, 1989 ISBN 1 85381 039 8, £11.99 Pbk

As a survivor of family violence I was attracted to Linda Gordon’s book from the start. Here, I hoped, would be a coherent study that would put the issues into a clear historical and political context. I have always held Gordon’s work in high regard and was pleased that it was she who should tackle this minefield of theoretical and methodological problems. In many ways I have not been disappointed: it is a very good study. In another way, however, I have serious reservations.

The research is based on case records...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Contents

- Editorial

- Fleurs du Mal or Second-Hand Roses?: Natalie Barney, Romaine Brooks, and the ‘Originality of the Avant-Garde’

- Poem

- Feminism and Motherhood: An American Reading

- Qualitative Research, Appropriation of the ‘Other’ and Empowerment

- Disabled Women and the Feminist Agenda

- Postcard From the Edge: Thoughts on the ‘Feminist Theory: An International Debate’ Conference at Glasgow University, July 1991

- Review Essay

- Reviews

- Noticeboard