Subhes C. Bhattacharyya

Asian economic development

Asia has been at the centre of global attention over the past three decades or so. According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB, 2017), developing Asia has transformed itself from a predominantly low-income region in the 1990s to a middle-income one in terms of per capita income measured in purchasing power parity (PPA). In 1991, more than 90% of the region’s population lived in low-income countries but by 2015, the majority of the population of the region live in middle-income countries. This dramatic transformation has happened fairly quickly by sustaining high levels of economic growth across the region.

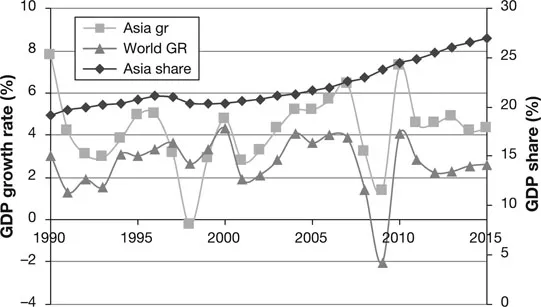

Before the 1980s, the strong economic development was limited to Four Tigers, namely Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan. Malaysia and Thailand joined the high growth path in the 1980s. Led by industrial development and economic growth in Japan, the ‘flying geese’ pattern, a catching-up process, initiated the Asian Miracle (see Kojima, 2000 for details on the flying geese model of growth). However, it is the double digit growth in China since its adoption of the open door policy and economic reform in late 1970s that has transformed the Asian economy beyond recognition. Between 1990 and 2015, China’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew 11-fold in constant 2005 dollar terms. Other Asian countries have also been influenced by this miraculous growth pattern and many joined the bandwagon. The region as a result grew faster than the world economy, with an average growth rate difference of 1.5% sustained over the period between 1990 and 2015, except for a short period during the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis (see Figure 1.1). The Asian economy continued to follow a relatively high growth path even after the global financial crisis of 2008. The share of Asian GDP in the global scene is thus showing a growing trend: from 19% in 1990, it has reached 27% in 2015 in constant 2005 US dollar terms. In purchasing power parity, the share becomes much higher.

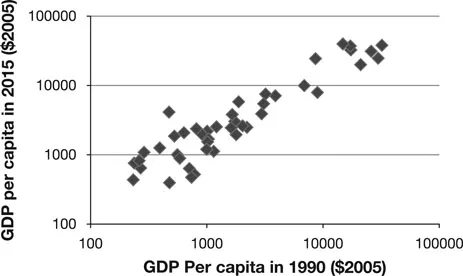

Faster economic growth has resulted in growing per capita income across the board. A plot of per capita income in 1990 versus that in 2015 (in logarithmic scale) shows the trend clearly (see Figure 1.2). Only a few countries are below US$1000 per capita income level, most of the countries are between US$1000 and US$10,000 range, while a handful are above the US$10,000 range. It can be seen that most of the countries are above the 45 degree line, showing that their 2015 per capita GDP has improved compared to the 1990 level.

Figure 1.1 GDP growth rate and share of the Asian economy

Figure 1.2 Scatter plot of GDP per capita in Asian countries

Asian countries achieved the above high growth path following two main approaches: by being the factory of the world and by driving domestic demand through the expansion of the middle-income class (Nakaso, 2015). The first driver was supported by the gradual relocation of industrial activities from developed countries to Asia to take advantage of the availability of a low-cost and skilled workforce, as well as a weak environmental and regulatory environment. This was further supported by trade liberalisation which increased trade volumes and led to growth in foreign direct investments. The expansion of export-oriented industrial activities created opportunities for better income that attracted rural agricultural labour force to factory sites in urban areas, resulting in large-scale migration and rapid urbanisation. The rise in income also expanded the size of the middle-income class, which became the second driver of economic expansion.

Unprecedented transformation of Asia

The economic growth has transformed the Asian way of living and has brought unprecedented changes. Four main transformations are worth mentioning, namely, a remarkable reduction in poverty incidence, the rise of the middle-income class, rapid urbanisation and demographic transition. Asia was infamous for its high incidence of poverty which is a common feature of low-income economies. However, the economic transformation has been successful in pulling millions of people out of poverty. Between 2002 and 2013, 707 million people in Asia and the Pacific have moved out of extreme poverty based on US$1.90 a day poverty line (2011 Purchasing Power Parity, PPP). East Asia has recorded the highest reduction in poverty level (from 31.9% in 2002 to 1.8% in 2013) but most of the sub-regions have managed to reduce poverty by 20% over this period. By 2013, only 9% of the region’s population (or 330 million) were living in extreme poverty condition, most of them concentrated in South Asia (ADB, 2016).

Simultaneously, the emergence and expansion of the middle class has changed the societal complexion beyond recognition. According to Kharas (2017), the first billion people of the middle class, reached around 1985, took more than 150 years from the Industrial Revolution but the next billion was added only in 21 years and the third billion was added in only nine years. Almost one half of the three billion middle class people lived in Asia by 2015 and almost 90% of the next billion entering this class will be in Asia. The better-off section of the population started to consume goods and services adopting the international trends, thereby offering a large potential consumer base which was hard to ignore. It is estimated that the middle-income class consumed US$35 trillion (2011 PPP value) in 2015 (Kharas, 2017). This represents a large domestic market for goods and services which thus offered the second impetus to growth. The size of the middle class is expected to grow rapidly over the next 15 years or so and by 2030, Asia is expected to account for 65% of the global middle-income class of 5.4 billion people.

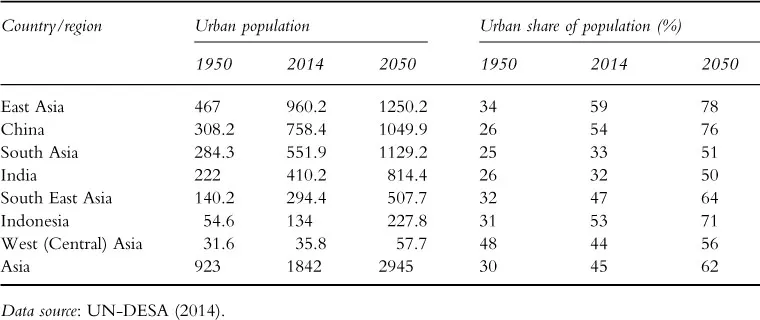

Rapid urbanisation has accompanied high economic growth in Asia. As Table 1.1 indicates, between 1990 and 2014, Asia has added more than 900 million urban people, 50% of whom came from East Asia. China alone added almost 450 million urban people. India and China account for 30% of the global urban population and more than a billion urban people. Asia had 17 megacities by 2016 (i.e. cities with more than ten million habitants), of which six megacities were in China and another five in India (UN, 2016). Between 2014 and 2050, India will add 404 million more while China will add another 292 million urban people. Overall, Asia will add 1.1 billion urban people during that period and will reach an urbanisation rate of 62% (UN-DESA, 2014).

Table 1.1 Urbanisation in Asia

Moreover, Asian demography is in transition. The population is expected to grow slowly compared to the previous decades. For example, East Asia will see a much slower growth in population and China will see a marginal fall in its population size by 2050 (from 1.376 billion in 2015 to 1.348 billion in 2050). On the other hand, Central Asia will maintain a high population growth rate but because of its low population base, the overall impact will be less noticeable. India will displace China to become the world’s most populous country by 2022 and by 2050 India is likely to have 1.7 billion people. Indonesia, Pakistan and Bangladesh are other major countries where population will grow. As life expectancy improves, the share of the population living over 65 years will gradually increase. By 2050, China will have an old-age dependency ratio (i.e. ratio of the population aged 65 and over to the population between 15 and 64) of 46.7% whereas the ratio will be higher than 70% in Japan. But Asia will continue to benefit from its youthful population structure and the ratio of working population to dependent population will remain favourable over the next decades. For example, India and Indonesia will have only 21% of their population aged 65 and over per 100 persons of working age (UN-DESA, 2015). Thus, a growing population and changes in the population structure will influence economic development and future development of Asia.