This is a test

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

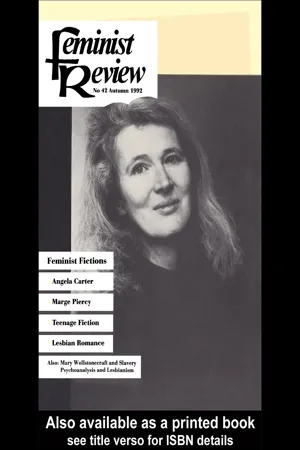

This theme issue is an exploration of the way in which feminist ideas appear in popular forms, especially feminist novelists, such as Angela Carter and Marge Piercy, have handled particular issues; it considers writing and it duscusses the popular genres that have been taken up by feminist writers - lesbian romance and stories for teenagers.

The central concern is with the problems of putting across feminist ideas in popular crative writing. Which ideas can be presented in this form? How will they be read? Are some forms more amenable to fiminism than others? Is feminism being distorted by popularization? Does feminism come across as a `message' that spoils the pleasure of reading?

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Feminist Review by The Feminist Review Collective in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Feminismo y teoría feminista. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Mary Wollstonecraft and the Problematic of Slavery

A traffic that outrages every suggestion of reason and religion...[an] inhuman custom.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

I love most people best when they are in adversity, for pity is one of my prevailing passions.

Collected Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft

History and texts before A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

In 1790, Mary Wollstonecraft became a major participant in contemporary political debate for the first time, due to her evolving political analysis and social milieu. In contrast to A Vindication of the Rights of Men in 1790 which drew primarily on the language of natural rights for its political argument, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) favoured a discourse on slavery that highlighted female subjugation. Whereas the Rights of Men refers to slavery in a variety of contexts only four or five times, the Rights of Woman contains over eighty references; the constituency Wollstonecraft champions—white, middle-class women— is constantly characterized as slaves. For her major polemic, that is, Mary Wollstonecraft decided to adopt and adapt the terms of contemporary political debate. Over a two-year period that debate had gradually reformulated its terms as the French Revolution in 1789 that highlighted aristocratic hegemony and bourgeois rights was followed by the San Domingan Revolution that primarily focused on colonial relations.

Wollstonecraft’s evolving commentaries on the status of European women in relation to slavery were made in response to four interlocking events: first, the intensifying agitation over the question of slavery in England that included the case of the slave James Somerset in 1772 and Phillis Wheatley’s visit in 1773; second, the French Revolution in 1789; third, Catherine Macaulay’s Letters on Education (1790) that forthrightly argued against sexual difference; and fourth, the successful revolution by slaves in the French colony of San Domingo in 1791.

This discourse on slavery employed by Wollstonecraft was nothing new for women writers, although it was now distinctly recontextualized in terms of colonial slavery. Formerly, in all forms of discourse throughout the eighteenth century, conservative and radical women alike railed against marriage, love, and education as forms of slavery perpetrated upon women by men and by the conventions of society at large.

Wollstonecraft’s Earlier Works, Received Discourse, and the Advent of the Abolitionist Debate

Prior to the French Revolution, Mary Wollstonecraft had utilized the language of slavery in texts from various genres. In Thoughts (1786), an educational treatise, Wollstonecraft talked conventionally of women subjugated by their husbands who in turn tyrannize servants, ‘for slavish fear and tyranny go together’ (Wollstonecraft, 1787:63). Two years later, in Mary, A Fiction (1788), her first novel written in Ireland during trying circumstances as a governess, the heroine decides she will not live with her husband and exclaims to her family: ‘I will work..., do anything rather than be a slave’ (Wollstonecraft, 1788:4b).1 Here as a case in point, Wollstonecraft inflects slavery with the orthodox conception of slavery that had populated women’s texts for over a century—marriage was a form of slavery; wives were slaves to husbands.

Wollstonecraft’s early conventional usage, however, in which the word slave stands for a subjugated daughter or wife was soon to complicate its meaning. From the early 1770s onward, a number of events from James Somerset’s court case to Quaker petitions to Parliament and reports of abuses had injected the discourse of slavery into popular public debate.

The Abolition Committee, for example, was formed on 22 May 1787, with a view to mounting a national campaign against the slave trade and securing the passage of an Abolition Bill through Parliament (Coupland, 1933:68). Following the establishment of the committee, abolitionist Thomas Clarkson wrote and distributed two thousand copies of a pamphlet entitled ‘A Summary View of the Slave-Trade, and of the Probable Consequences of Its Abolition’ (Clarkson, 1808:276–85 and passim). Wollstonecraft’s friend, William Roscoe, offered the profits of his poem The Wrongs of Africa’ to the committee. The political campaign was launched on the public in full force (Craton, 1974: chapter 5).

Less than a year after the Abolition Committee was formed, Wollstonecraft’s radical publisher, Joseph Johnson, co-founded a radical periodical entitled the Analytical Review. Invited to become a reviewer, Wollstonecraft’s reviews soon reflected the new influence of the abolition debate (Sunstein, 1975:171). One of the earliest books she critiqued in April 1789 was written by Britain’s most renowned African and a former slave; Wollstonecraft was analyzing a text based on specific experiences of colonial slavery for the first time. Its title was The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African Written by Himself, in which Equiano graphically chronicles being kidnapped from Africa, launched on the notorious Middle Passage, and living out as a slave the consequences of these events.

While the Analytical Review acquainted the public with old and new texts on the current debate, Wollstonecraft was composing an anthology for educating young women that also reflected her growing concerns. Published by Joseph Johnson and entitled The Female Reader: or Miscellaneous Pieces for the Improvement of Young Women, the textbook cum anthology included substantial extracts promoting abolition. It included Sir Richard Steele’s rendition from The Spectator of the legend of Inkle and Yarico, Anna Laetitia Barbauld s hymn-in-prose, ‘Negro-woman’, about a grieving mother forcibly separated from her child, and a poignant passage from William Cowper’s poem, ‘The Task’, popular with the contemporary reading public:

I would not have a slave to till my ground,

To carry me, to fan me while I sleep,

And tremble when I wake, for all the wealth

That sinews bought and sold have ever earn’d.

No: dear as freedom is, and in my heart’s

Just estimation priz’d above all price,

I had much rather be myself the slave,

And wear the bonds, than fasten them on him

(Wollstonecraft, 1789:29–31, 171, 321–2).

A series of events then followed one another in rapid succession that continued to have a bearing on the reconstitution of the discourse on slavery. In July 1789, the French Revolution erupted as the Bastille gaol was symbolically stormed and opened. Coinciding with the French Revolution came Richard Price’s polemic, Edmund Burke’s response, and then Wollstonecraft’s response to Burke and her review of Catherine Macaulay’s Letters on Education. Meanwhile, in September and the following months, Wollstonecraft reviewed in sections the antislavery novel Zeluco: Various Views of Human Nature, Taken from Life and Manners, Foreign and Domestic, by John Moore. Let me back up and briefly elaborate how all this attentiveness to colonial slavery affected public debate and Mary Wollstonecraft’s usage of the term.

The French Revolution

On 4 November 1789, Wollstonecraft’s friend, the Reverend Richard Price, Dissenting minister and leading liberal philosopher, delivered the annual sermon commemorating the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 to the Revolution Society in London. The society cherished the ideals of the seventeenth-century revolution and advocated Dissenters’ rights. This particular year there was much for Dissenters to celebrate. Basically, Price applauded the French Revolution as the start of a liberal epoch: ‘after sharing in the benefits of one revolution,’ declared Price [meaning the British seventeenth-century constitutional revolution], ‘I have been spared to be a witness to two other Revolutions, both glorious’ (Price, 1790:55). The written text of Price’s sermon, Discourse on the Love of Our Country, was reviewed by Wollstonecraft in the Analytical’s December issue. A year later, on 1 November 1790, Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France that attacked both Price and his sermon was timed to be published on the anniversary of Price’s address. It soon became a topic of public debate. Several responses quickly followed.

As the first writer to challenge Burke’s reactionary polemic, Wollstonecraft foregrounded the cultural issue of human rights in her title: A Vindication of the Rights of Men. It immediately sold out. Not by political coincidence, she composed this reply while evidence about the slave trade was being presented to the Privy Council during the year following the first extensive parliamentary debate on abolition in May 1789. The Rights of Men applauded human rights and justice, excoriated abusive social, church and state practices, and attacked Burke for hypocrisy and prejudice. She argued vehemently for a more equitable distribution of wealth and parliamentary representation. By 4 December the same year, Wollstonecraft had revised the first edition and Johnson rapidly turned out a second one in January 1791 (Tomalin, 1974).

In The Rights of Men, Wollstonecraft also frontally condemns institutionalized slavery:

On what principle Mr. Burke could defend American independence, I cannot conceive; for the whole tenor of his plausible arguments settles slavery on an everlasting foundation. Allowing his servile reverence for antiquity, and prudent attention to selfinterest, to have the force which he insists on, the slave trade ought never to be abolished; and, because our ignorant forefathers, not understanding the native dignity of man, sanctioned a traffic that outrages every suggestion of reason and religion, we are to submit to the inhuman custom, and term an atrocious insult to humanity the love of our country, and a proper submission to the laws by which our property is secured (Wollstonecraft, 1790:23–4).

In The Rights of Men, Wollstonecraft explicitly argues for the first time that no slavery is natural and all forms of slavery, regardless of context, are human constructions. Her scorching words to Burke about his situating slavery ‘on an everlasting foundation’ (in the past and the future) sharply distinguishes her discourse from her more orthodox invocations of slavery in Thoughts and Mary. Contemporary events have begun to mark the discourse on slavery in a particular and concrete way.

In particular, Wollstonecraft challenges the legal situation. In The Rights of Men, she graphically represents slavery as ‘authorized by law to fasten her fangs on human flesh and. eat into the very soul’ (Wollstonecraft, 1790:76). None the less, although she supports abolition unequivocally, she considers ‘reason’ an even more important attribute to possess than physical freedom. ‘Virtuous men,’ she comments, can endure ‘poverty, shame, and even slavery’ but not the ‘loss of reason’ (Wollstonecraft, 1790:45, 59).

The same month that Wollstonecraft replied to Burke, she favourably reviewed Catherine Macaulay Graham’s Letters on Education. Macaulay’s argument against the accepted notion that males and females had distinct sexual characteristics was part of the evolving discourse on human rights that connected class relations to women’s rights. Macaulay also expropriated the language of physical bondage and wove it into her political argument. Denouncing discrimination against women throughout society, Letters also rails against ‘the savage barbarism which is now displayed on the sultry shores of Africa’ (Ferguson, 1985:399). Macaulay takes pains to censure the condition of women ‘in the east’—in harems, for example—and scorns the fact that men used differences in ‘corporal strength.in the barbarous ages to reduce [women] to a state of abject slavery’ (Ferguson, 1985:403–4). Macaulay’s historical timing separates her from earlier writers who used this language; by 1790 slavery had assumed multiple meanings that included the recognition, implied or explicit, of connexions between colonial slavery and constant sexual abuse.

In The Rights of Men,however, Wollstonecraft had not exhibited any substantial attention to the question of gender. But, after she read Macaulay, her discourse on gender and rights shifted. Notably, too, as one edition after another of A Vindication of the Rights of Men hit the presses, Johnson was concurrently publishing Wollstonecraft’s translation of Christian Gotthilf Salzmann’s Elements of Morality for the Use of Children. In the preface to this educational treatise, Wollstonecraft pointedly inserted a passage of her own, enjoining the fair treatment of Native Americans. In terms of democratic colonial relations as they were then perceived, Wollstonecraft rendered Salzmann more up to date. There was, however, still more to come before Wollstonecraft settled into writing her second Vindication in 1792.

First of all, information about slavery continued to flow unabated in the press. According to Michael Craton, ‘William Wilberforce was able to initiate the series of pioneer inquiries before the Privy Council and select committees of Commons and Lords, which brought something like the truth of slave trade and plantation slavery out into the open between 1789 and 1791’ (Craton, 1974:261). None the less, in April 1791, the Abolition Bill was defeated in the House of Commons by a vote of 163 to 88, a massive blow to the antislavery campaign.

Just as much, if not perhaps more to the point, in August of that year, slaves in the French colony of San Domingo (now Haiti) revolted, another crucial historical turning point. The French Caribbean had been ‘an integral part of the economic life of the age, the greatest colony in the world, the pride of France, and the envy of every other imperialist nation’ (James, 1963:ix).

The conjunction of these events deeply polarized British society. George III switched to the proslavery side, enabling faint-hearted abolitionists to change sides. Meanwhile, radicals celebrated. This triumphant uprising of the San Domingan slaves forced another angle of vision on the French Revolution and compounded the anxiety that affairs across the Channel had generated. Horrified at the threat to their investments and fearful of copycat insurrections by the domestic working class as well as by African Caribbeans, many panic-stricken whites denounced the San Domingan Revolution (Klingberg, 1926:88–95).

Although no one spoke their pessimism outright, abolition was temporarily doomed. When campaigners remobilized in 1792, they were confident of winning the vote and refused to face the implications of dual revolutions in France and San Domingo. Proslaveryites, now quite sanguine, capitalized on the intense conflicts and instigated a successful policy of delay. A motion for gradual abolition—effectively a plantocratic victory—carried in the Commons by a vote of 238 to 85.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

The composition of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman started in the midst of these tumultuous events, its political ingredients indicating Wollstonecraft’s involvement in all these issues. Indeed, Mary Wollstonecraft seems to have been the first writer to raise issues of colonial and gender relations so tellingly in tandem.

More than any previous text, the Rights of Woman invokes the language of colonial slavery to impugn female subjugation and call for the restoration of inherent rights. Wollstonecraft’s eighty-plus references to slavery divide into several categories and subsets. The language of slavery—unspecified—is attached to sensation, pleasure, fashion, marriage and patriarchal subjugation. It is also occasionally attached to the specific condition of colonized slaves.

Wollstonecraft starts from the premise that all men enslave all women and that sexual desire is a primary motivation: ‘I view, with in...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Copyright Page

- Editorial: Feminist Fictions

- Angela Carter's the Bloody Chamber and the Decolonization of Feminine Sexuality

- Feminist Writing: Working with Women's Experience

- Unlearning Patriarchy: Personal Development in Marge Piercy's Fly Away Home

- Are They Reading Us? Feminist Teenage Fiction

- Sexuality in Lesbian Romance Fiction

- A Psychoanalytic Account for Lesbianism

- Mary Wollstonecraft and the Problematic of Slavery

- Reviews

- Noticeboard