This is a test

- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Clinical Immunology of the Dog and Cat

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This second edition of a bestseller details the manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of immune-related disease in the dog and cat. It is illustrated throughout in full color, to show and explain to the reader as clearly as possible the complicated principles of disease and immunodiagnostic tests, supported by clinical cases, gross and histopatho

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Clinical Immunology of the Dog and Cat by Michael Day in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medizin & Veterinärmedizin. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 BASIC IMMUNOLOGY

Michael J. Day

INTRODUCTION

The immune system is one of the most complex and diverse of body components. This complexity has evolved to enable efficient neutralization of the myriad of potential pathogens that may be encountered at any site within the body during a lifetime. The same complexity, however, also provides scope for failure of the normal immunological regulatory mechanisms and the development of immune-mediated diseases.

There is a vast amount of knowledge concerning the workings of the mammalian immune system, a system which encompasses an array of cells and their surface molecules, together with soluble factors released from them and the genes which encode these substances. The basic components of the immune system have been conserved throughout evolution, and there is often a high degree of homology between similar molecules in different species. The immune systems of man and laboratory animals have been best characterized and this understanding has been extrapolated to other species.

Among domestic animals, the immune systems of the dog and cat have only been examined in detail in relatively recent times. The use of the dog as a model for transplantation surgery, and of the cat as a model for the study of virally induced neoplasia (feline leukaemia virus [FeLV]) or immunodeficiency (feline immunodeficiency virus [FIV]), has led to the application of cellular and molecular techniques to characterize basic facets of the canine and feline immune systems. The recent availability of the canine genome has revolutionized our ability to dissect the immune system of the dog and develop molecular tools for the characterization of immune-mediated diseases in this species. Alignment of the canine and human genomes has shown 75% sequence similarity, further confirming the value of investigation of spontaneously arising canine disease as a model for the human counterpart. A partial version of the feline genome is now available.

This chapter overviews the major components of the immune system at the tissue, cellular and molecular levels, where possible giving details of specific parameters as they apply to the dog and cat. Such a review cannot be exhaustive, but it forms the basis for discussion of disease mechanisms in later chapters.

THE IMMUNE SYSTEM: AN OVERVIEW

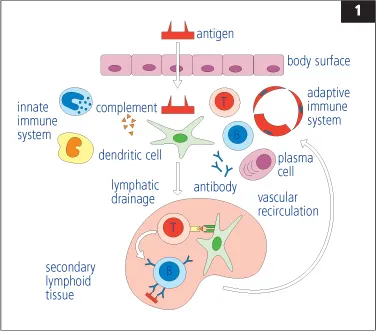

1 Overview of the immune response. When foreign antigen enters the body it first encounters the cells and molecules of the non-antigen specific, innate immune system. Antigen is taken up by dendritic antigen presenting cells and transported to the regional lymphoid tissue, where there is induction of the antigen-specific adaptive immune response. Activated cells of the adaptive immune system recirculate to the site of antigen exposure via the vasculature, where these cells and their products amplify the local immune response. The dendritic cell is the link between the innate and adaptive immune systems.

The immune system has both innate and adaptive components (1). The innate response is a first-line of body defence and consists of the non-specific effects of epithelial or mucosal barriers (e.g. physical structures such as cilia and secreted factors such as enzymes), together with the action of phagocytic cells (neutrophils, macrophages and dendritic cells), inflammatory mediators and the alternate pathway of the complement system. A particular subset of T lymphocytes, the ΓΔ T cells, which express a unique surface receptor, may also be considered part of the innate immune system, as they are found in high numbers at external surfaces and are particularly responsive to bacterial antigens. One of the most significant recent immunological advances has been a re-evaluation of the importance of innate immunity. It is now appreciated that the initial interaction between foreign antigen and the dendritic antigen presenting cell (APC) determines the nature of the subsequent adaptive immune response. The adaptive immune response involves the selective activation of lymphoid cells with specificity for the pathogen, and the subsequent action of pathogen-specific antibodies or effector cells. Adaptive immunity develops over time and specific immunological memory of the pathogen is retained.

ANTIGENS

An antigen is generally considered as a substance that can initiate an immune response. Technically, an ‘antigen’ is defined only by its ability to bind to antibody, whereas an ‘immunogen’ is capable of inducing antibody production. Most antigens are foreign to an individual; they include microbes, chemicals and plant-derived substances as well as tissue from genetically dissimilar individuals of the same species (alloantigen) or a different species (xenoantigen). In autoimmune disease, components of the body may also become antigenic (autoantigens).

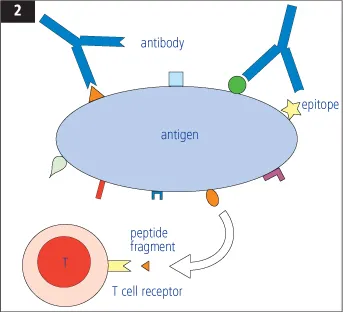

2 Antigens. Antigens have a set of antigenic epitopes (determinants) that are recognized by antibodies and TCRs of the adaptive immune system. Each antibody recognizes one epitope rather than the entire antigen, and TCRs recognize small peptide fragments derived from epitopes.

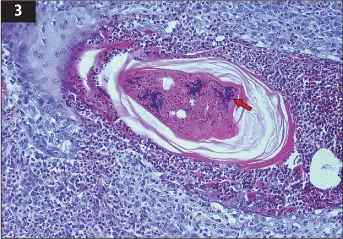

3 Antigenic epitopes. Colonies of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in the lumen of a hair follicle of a dog with deep pyoderma (arrowed). Each Staphylococcus organism may have numerous constituent antigens.

The most effective antigenic (immunogenic) substances are large, insoluble molecules (>10 kD in molecular weight), which have chemical complexity and a stable three-dimensional structure. Biologically active substances (e.g. microbes) are particularly antigenic.

A single antigen may have numerous epitopes or determinants, each of which is capable of inducing an immune response (2–4), but some of which may be more effective in so doing (immunodominant).

Some small chemical groups (haptens) are unable to induce an immune response unless chemically conjugated to a larger protein molecule (carrier protein). This mechanism is thought to underlie many adverse reactions to drugs (5).

The immunogenicity of antigens can be enhanced by incorporating them into an adjuvant (e.g. Freund’s adjuvant or alum), which acts by non-specific immune stimulation and by forming a slow-release depot of antigen.

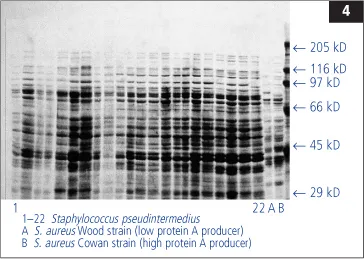

4 Antigenic epitopes. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis separating the components of 22 isolates of S. pseudintermedius by molecular weight. Each band in the gel may represent one or more epitopes. The specificity of antibody in the serum of an infected dog for these epitopes can be determined by the technique of western blotting. (Photograph courtesy D.H. Shearer.)

5 Haptens. This German Shepherd Dog was treated with ketoconazole for disseminated aspergillosis and subsequently developed lesions of the planum nasale and periorbital skin consistent with cutaneous drug eruption. In such cases the drug may act as a hapten by binding to native protein within tissue and inducing an immune response to novel epitopes thus formed.

ANTIBODIES (IMMUNOGLOBULINS)

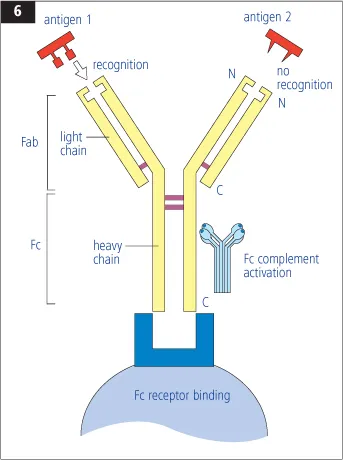

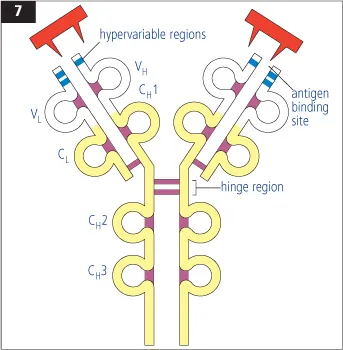

Antibodies are generated as part of an immune response and, when formed, are able to bind to antigens. Although immunoglobulin (Ig) molecules take different forms (classes and subclasses), each has a similar basic structure, consisting of a Y-shaped unit of two heavy and two light polypeptide chains (6, 7). There are five forms of heavy chain (α, Γ, μ, Δ and ε), the use of which gives rise to the five classes of Ig (IgA, IgG, IgM, IgD and IgE, respectively), and each may associate with either of the two forms of light chain (κ and λ). In the dog and cat, λ chain is more commonly utilized than κ. Subclasses of Ig are defined by subtle modifications to the sequence and structure of the constant regions.

6 Basic structure and function of Ig. The Ig unit consists of two identical light polypeptide chains and two identical heavy polypeptide chains linked together by disulphide bonds (purple). The position of the amino-(N) and carboxy- (C) terminal ends of the polypeptide chains are indicated. The unit has two antigen-binding fragments (Fab) and a constant region (Fc), which interacts with crystallizable fragment receptors on cells or activates complement.

IgG

This is the major serum Ig, which may diffuse readily to the extravascular tissue space. It comprises a single Ig unit and potentially binds two antigenic epitopes. There are four subclasses of IgG in the dog (IgG1–IgG4), defined at both the protein and gene level. Three subclasses have been recognized in the cat, but to date only a single IgG encoding gene has been characterized. The relative serum concentration of the subclasses in normal dogs is IgG1 and IgG2>IgG3 and IgG4, and there are electrophoretic similarities between IgG1 and IgG3 (cathodal) and IgG2 and IgG4 (anodal). Unfortunately, there remains much confusion regarding canine IgG subclasses due to the persistence of old nomenclature and the commercial availability of a set of antisera that purport to detect IgG subclasses, but are in fact not subclass specific. In dogs and cats, IgG is largely unable to cross the placental barrier and maternal immunity must be conferred to neonates via colostrum.

7 Domain structure of Ig. The N-terminal end of the Ig molecule is characterized by a variable amino acid sequence in both the heavy and light chains, referred to as the VH and VL regions, respectively. Within the variable regions are areas of sequence hypervariability. The remainder of the molecule has a relatively constant sequence. The constant portion of the light chain is known as the CL region and the constant portion of the heavy chain is divided into three subregions known as CH1, CH2 and CH3. Each subregion of the molecule has a globular ‘domain’ structure stabilized by intrachain disulphide bonds. The hinge region is a segment of the heavy chain between CH1 and CH2 that includes interchain disulphide bonds. The antigen binding portions of the molecule are flexible about the hinge region.

IgM

This molecule comprises five basic Ig units linked together by a joining (J) chain (8). A single IgM molecule has ten antigen binding sites and IgM is therefore very efficient at agglutinating particulate antigens. The size of the molecule generally precludes it leaving the bloodstream.

IgA.

IgA may be found as a monomer of a single Ig unit (two antigen binding sites) or as a dimer with a J chain (four antigen binding sites) (9). There are species differences in the relative distribution of IgA monomers or dimers. In man, serum IgA is monomeric, while the IgA that is found at mucosal surfaces is a dimer. In contrast, both serum and mucosal IgA is dimeric in dogs and cats, which likely reflects the fact that most of this Ig is produced at mucosal sites. Because of the dimeric nature ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY OF THE DOG AND CAT Second Edition, Revised And Updated

- Dedication

- Disclaimer

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- PREFACE (First Edition)

- PREFACE (Second Edition)

- CONTRIBUTORS

- ABBREVIATIONS

- KEY TO SYMBOLS

- 1 BASIC IMMUNOLOGY

- 2 IMMUNOPATHOLOGICAL MECHANISMS

- 3 THE BASIS OF IMMUNE-MEDIATED DISEASE

- 4 IMMUNE-MEDIATED HAEMATOLOGICAL DISEASE

- 5 IMMUNE-MEDIATED SKIN DISEASE

- 6 IMMUNE-MEDIATED MUSCULOSKELETAL AND NEUROLOGICAL DISEASE

- 7 IMMUNE-MEDIATED ALIMENTARY DISEASE

- 8 IMMUNE-MEDIATED RESPIRATORY AND CARDIAC DISEASE

- 9 IMMUNE-MEDIATED ENDOCRINE DISEASE

- 10 IMMUNE-MEDIATED RENAL AND REPRODUCTIVE DISEASE

- 11 IMMUNE-MEDIATED OCULAR DISEASE

- 12 IMMUNODEFICIENCY DISEASE

- 13 IMMUNE SYSTEM NEOPLASIA

- 14 MULTISYSTEM AND INTERCURRENT IMMUNE-MEDIATED DISEASE

- 15 DISEASES OF LYMPHOID TISSUE

- 16 IMMUNOTHERAPY

- 17 VACCINATION

- GLOSSARY

- INDEX