- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Intergroup Relations

About this book

This book focuses on the stereotypes, prejudices, and discriminatory behavior of individuals and the manner in which these cognitions, feelings, and behaviors affect others and are affected by them, concentrating in relations among individuals as they are affected by their own group memberships.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1. Stereotypes

Chapter Outline

- Defining Stereotypes

- Measuring Stereotypes

- Categorization

- Historical Origins of Stereotyping

- Biased Labeling

- The Structure and Processing of Stereotype Information

- The Structure of Stereotypes

- Processing in Stereotype Networks

- Affect Associated with Stereotypes

- Mood Associated with Stereotypes

- Associative Network Models and Expectancy Confirmation

- Stage I: Information Acquisition

- Stage II: Information-Processing Biases

- Stage III: Self-Fulfilling Prophecies

- Changing Stereotypes

- Strengthening or Creating Positive Links

- Weakening Negative Links

- Subtyping and Activating Alternative Categories

- Altering Biased Labeling

- Summary

To consider every member of a group as endowed with the same traits saves us the pains of dealing with them as individuals. (Allport, 1954, p. 169)

Rwanda is a small republic in central Africa. In 1994 the presidents of Rwanda and the neighboring republic of Burundi were killed under mysterious circumstances in a plane crash at the airport outside of the capital of Rwanda. Their deaths touched off a bloody civil war in Rwanda. Even the most conservative estimates of the resulting carnage indicate that more than 200,000 lives were lost. The antagonists in this civil war were two ethnic groups, the Hutu, who are the majority group in Rwanda, and the Tutsi, who are the minority group. Like most such struggles, this one has a long history, but its modern antecedents can be traced to the period just before and after Rwanda achieved independence from Belgium in 1962.

For most of the colonial period the two ethnic groups lived together relatively peacefully. In the years immediately prior to independence, two political organizations existed in Rwanda, one controlled by the Tutsi and one controlled by the Hutu (Kuper, 1977). Both organizations were ideologically moderate. For instance, a Hutu manifesto in 1957 declared that, although the principal problem of the country was the domination of one group by the other (the Tutsi are economically dominant), both groups shared a common ancestry and in this sense were brothers. The Tutsi-dominated party (Union Nationale Rwandaise [UNAR]), although elitist in defense of Tutsi privilege, expressed a commitment to fight against ethnic hatred.

As independence approached, ethnically based political tensions escalated. Increasingly, the common ground between the two groups diminished, and an accentuation of group differences occurred. The increasing use of repression by the economically dominant Tutsi minority led to a fear of aggressive retaliation by the Hutu. The aggressiveness imputed to the Hutu was used to justify additional repression. The spark that ignited this highly flammable mixture was the beating and rumored murder of a Hutu subchief. The response was a peasant uprising in which Hutu tribesmen burned thousands of Tutsi homes and killed some Tutsies. The Tutsi reaction consisted of the summary arrest, torture, and execution of Hutu leaders. Fear and suspicion gripped the country. Each group increasingly perceived the other group in dehumanized terms, as bloodthirsty barbarians. Each group blamed the other for aggression against its members.

Elections just before independence brought the Hutu majority to power in 1961. Tutsi were removed from positions of authority, many were executed, and UNAR was eradicated. The Tutsi mounted military raids against the Hutu, who countered with massive reprisals. According to de Heusch (1964), “From then on every Tutsi, in the interior as well as the exterior, whether or not supportive of these military adventures . . . [was] considered an enemy of the country” (Kuper, 1977, p. 193). The categorical process was complete. All differentiation among the Tutsi was obliterated.

The next atrocity was committed by the Hutu in response to an invasion by the Tutsi from neighboring Burundi in 1963. “Hutu, armed with clubs, pangas and spears, methodically began to exterminate all Tutsi in sight, men, women, and children” (Kuper, 1977, p. 196). An estimated 10,000 people were slaughtered before the massacre ended. The hatred created by this massacre continued to seethe beneath the surface of Rwandan life for the next three decades. Incidents of violence gradually increased until the explosion into civil war in 1994.

The descent into social chaos in 1963, which set the stage for the bloody civil war of 1994, illustrates the role of group perceptions in intergroup relations. From an initial stance of some common goals, tempered with expressions of reservations and suspicion, the groups came to attribute hostility and aggressiveness to each other. Outgroup members were perceived as hated barbarians, a view that was ultimately used to justify genocide.

Of course, outgroup perceptions are usually not as negative or overgeneralized as those between the Tutsi and the Hutu, nor are the consequences this tragic. Nonetheless, our views of other groups, especially our stereotypes of these groups, are often negative and overgeneralized, and they do have important effects on our behavior toward them and on their reactions to us. What are stereotypes and how can they come to have such destructive effects?

Defining Stereotypes

Journalists often do more than report on society. They also provide valuable insights into its fundamental nature. Walter Lippman, one of the great journalists of the twentieth century, gave us the concept of stereotypes (Lippman, 1922). He argued that “the real environment is altogether too big, too complex, and too fleeting, for direct acquaintance. We are not equipped to deal with so much subtlety, so much variety, so many permutations and combinations. . . . We have to reconstruct it on a simpler model before we can manage with it” (p. 16). Stereotypes are one of the simplifying mechanisms people use to make a complex social world more manageable. But Lippman also recognized that a stereotype “is not merely a way of substituting order for the great blooming, buzzing confusion of reality. It is all these things and more. It is the guarantee of self-respect, it is our projection upon the world of our own sense of value, of our position, and our own rights. The stereotypes are . . . highly charged with feelings that are attached to them” (p. 96). Thus stereotypes serve many functions, including helping people to maintain their selfesteem and justify their social status (cf. Jost & Banaji, in press). To serve these functions, our perceptions of the traits possessed by other groups are often distorted.

The early literature on stereotypes typically condemned them as unduly negative, overgeneralized, and incorrect (cf. Brigham, 1971). Later theorists, however, argued that stereotypes were no different from generalizations about nonsocial categories (e.g., the characteristics of birds) (Brigham, 1971; McCauley, Stitt, & Segall, 1980; Stephan, 1985). All generalizations organize and simplify the world. By stressing the similarity of generalizations about social groups to generalizations about nonsocial stimuli, the newer definitions avoided condemning stereotypes as morally wrong and pointing an accusatory finger at people who possess them. In accord with the newer definitions, we will define stereotypes as the traits attributed to social groups.

Stereotypes are frequently useful in everyday social interaction and often perform a valuable function. They can provide us with sets of guidelines that shape our interactions with physicians, nurses, waitpersons, accountants, professors, infants, schizophrenics, depressed people, shy people, and so on. For instance, knowing that someone is schizophrenic and that schizophrenics are likely to have delusions and hallucinations and that their affect may be flat or inappropriate prepares one for interaction with that person.

For intergroup relations, however, stereotypes are important primarily when they are negative, overgeneralized, or incorrect, because then they have detrimental effects on intergroup interactions. Stereotypes have detrimental effects because of the expectations they create concerning the behavior of others. When these expectations are negative, they lead us to anticipate negative behaviors from outgroup members. When the expectations are overgeneralized, they lead us to anticipate that most outgroup members will behave in similar ways. They make it less likely that we will treat outgroup members as individuals—each with his or her own unique qualities. And when stereotypes are incorrect, they can cause suffering to those who are misperceived and lead to misunderstanding and conflict.

The next section surveys techniques of measuring stereotypes, after which their origins, their implications, and how they can be changed are discussed.

Measuring Stereotypes

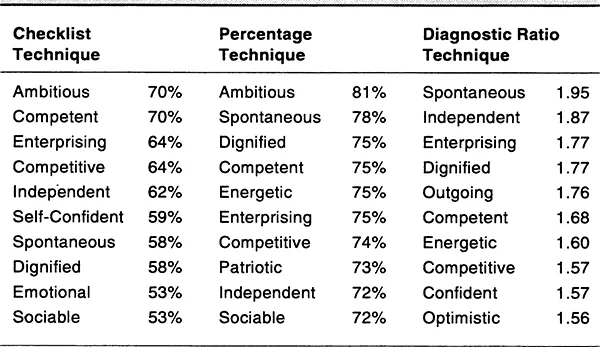

Three techniques for empirically measuring stereotypes have achieved considerable acceptance. The first is the original technique devised by Katz and Braly (1933), the checklist technique (before reading on, take a minute to read box 1.1). This technique is used to uncover the consensus in one group’s views of another by asking respondents to indicate the traits that characterize the other group. Respondents select from a large list of trait adjectives those that they feel characterize a given group. The stereotype consists of those traits that are nominated by the greatest number of respondents. For instance, in a study of college students in Russia, the respondents were given a list of 115 traits and asked to indicate the 15 that best characterized Americans (Stephan, Ageyev, Stephan, Abalakina, Stefanenko, & Coates-Schrider, 1993). Table 1.1 on page 7 lists the 10 most frequently nominated traits. Is this list different from your own stereotype of Americans? If so, why do you think these differences exist?

The second technique, the percentage technique, is the most widely used. The percentage technique is used to determine the prevalence of a set of traits in a given group (Brigham, 1971). Respondents are given a large list of traits and asked to indicate the percentage of group members who possess each trait. The stereotype consists of the traits perceived to be possessed by the highest percentage of group members. In the Stephan et al. study cited, a second sample of Russian students was asked to indicate the percentage of Americans who possessed each of 38 traits. The 10 traits with the highest percentages are also listed in table 1.1. Notice that though the two techniques yield similar results, there are also some differences.

The third technique, the diagnostic ratio, is used to determine the traits that uniquely distinguish a given group from people in general (Martin, 1987; McCauley & Stitt, 1978). As in the percentage method, respondents are asked to indicate the percentage of group members who possess each of a list of traits. Then they are asked to indicate the percentage of people in general who possess these traits. A diagnostic ratio indicating the degree to which the group is perceived to differ from people in general is then calculated for each trait. This is done by dividing the percentage of group members who possess the trait by the percentage of people in general who possess the trait. The stereotype consists of those traits with the highest ratios. The Russian students were also asked to indicate the percentage of people in general who possessed each of the 38 traits. The diagnostic ratios that were calculated from their responses appear in table 1.1. The stereotypes emerging from the diagnostic ratios are somewhat different from the stereotypes using the checklist and percentage techniques. There is only a 60 percent agreement with each of the other techniques. The reason for this difference is that some of the traits that appear using the checklist and the stereotype techniques (e.g., sociable, ambitious) are traits that Russian students think characterize people in general—that is, they are not unique to Americans.

Box 1.1 Measuring Stereotypes with an Adjective Checklist

Using the following list, select the 10 adjectives that best characterize Americans. Then seiect the 10 adjectives that best characterize Russians.

| Optimistic | Friendly |

| Aggressive | Independent |

| Outgoing | Tough |

| Patient | Secretive |

| Wasteful | Humorous |

| Dignified | Passive |

| Restrained | Irresponsible |

| Materialistic | Truthful |

| Oppressed | Confident |

| Serious | Kind |

| Competitive | Ambitious |

| Conservative | Expert |

| Spontaneous | Sociable |

| Patriotic | Hospitable |

| Disciplined | Progressive |

| Energetic | Industrious |

| Proud | Strong |

| Emotional | Obedient |

| Adaptable | Enterprising |

Later you will have an opportunity to compare your answers to those of Russian and American students.

Studies comparing techniques of measuring stereotypes suggest that most techniques yield similar results. However, as it was intended to, the diagnostic ratio does provide a different view of the content of stereotypes (Jonas & Hewstone, 1986; McCauley & Stitt, 1978; McCauley, Stitt, & Segall, 1980; Stephan et al., 1993). All techniques of measuring stereotypes have in common an attempt to assess the traits associated with social categories. But do all social categories have stereotypes associated with them? Aren’t people more apt to stereotype some groups than others? These questions are examined next.

Table 1.1 Russians’ Stereotypes of Americans

Source: Stephan et al., 1993.

Categorization

If perceptual experience is ever . . . free of categorical identity, it is doomed to be a gem, serene, locked in the silence of private experience. (Bruner, 1973, p. 9)

The cognitive basis of stereotyping is categorization. In fact, stereotypes, as defined here, are an almost inevitable consequence of categorization. To create social categories, we focus on the characteristics that make the people in that category similar and that distinguish them from other people. Categories such as “disabled person,” “Protestant,” or “Caucasian” all refer to qualities that make the people within these categories similar—their physical abilities, their religious beliefs, or their race. When we categorize pe...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Social Psychology Series

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- 1 Stereotypes

- 2 Theories of Prejudice

- 3 The Contact Hypothesis in Intergroup Relations

- 4 Social Identity, Self-Categorization, and Intergroup Attitudes

- 5 Intercultural Relations

- 6 Intergroup Conflict and Its Resolution

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Intergroup Relations by Cookie W Stephan,Walter G Stephan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.