eBook - ePub

From Reverie to Interpretation

Transforming Thought into the Action of Psychoanalysis

This is a test

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

From Reverie to Interpretation

Transforming Thought into the Action of Psychoanalysis

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Bion's identification of reverie as a psychoanalytic concept has drawn attention to a dimension of the analyst's experience with tremendous potential to enrich our interpretive understanding. The courage of these authors in revealing their own process of reverie as transformed into the action of psychoanalysis will inspire and foster further investigation of this fruitful yet heretofore infrequently explored area of psychoanalytic discovery.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access From Reverie to Interpretation by Dana Blue, Caron Harrang, Dana Blue, Caron Harrang in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Escape within

Sabah Al-Dhaher

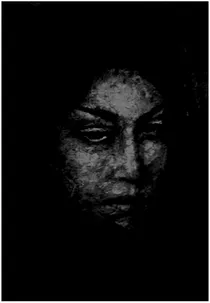

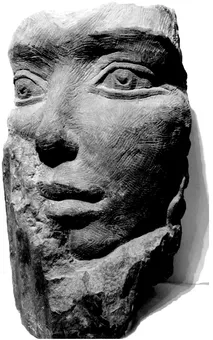

It is the loss and hardships of life that make us draw on our inner strength and that temper the soul. My sculpture and painting are a tribute to those who go through the grieving process of loss, especially in war-torn countries. When I think of Iraq, my homeland, what comes to mind is an image of an Iraqi female whose face holds all those unspoken words—words of love, loss, and sadness (Figures 1–3).

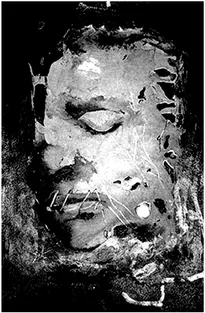

Before I could create the work I now produce, I had to move through a deeply personal process to reconnect to my own artist within. In 1998 I painted Escape Within, my first work of art since arriving in Seattle as a political refugee in 1993 (book cover). Escape Within, painted with coffee and coloured ink, was the first necessary step in the work of facing and transforming my own grief and sense of trauma at having lived through the Iraq−Iran war during the 1980s. Escape Within captures my experience of having been tortured in an Iraqi prison, of having escaped Iraq in 1991, and of having spent two and a half years in a prisoner-of-war camp in the desert of Saudi Arabia before finally arriving in the United States as a political refugee (Figure 4).

The process I entered in creating Escape Within was for me one of reverie, in that by releasing myself to the effect of the sepia tones of the coffee on paper, some images started to appear or emerge with an

Figure 1. Sabah Al-Dhaher, Iraqi Widow, 2005; coffee and coloured ink on paper, 36 × 24 inches. Private collection.

Figure 2. Sabah Al-Dhaher, Songs of Sorrow, 2005; coffee and coloured ink on paper, 5 × 7 inches. Collection of the artist.

Figure 3. Sabah Al-Dhaher, Traces, 2008; carved sandstone, 30 inches high. Collection of the artist.

Figure 4. Sabah Al-Dhaher, Hunger Strike, 1998; coffee and coloured ink on paper, 12 × 16 inches. Collection of the artist.

incredible flow and ease. It was like magic, watching my hand flow with this beautiful dance between the brush and the white surface of the paper, revealing something I was not yet aware of in myself. The intertwining of those traces between the figure and the background, the undefined face as it slowly revealed itself from my own subconscious and my memories, all came together in a moment of revelation that I was not conscious of at the time.

When I started working on Escape Within I had no intention or predetermined idea of how it should look. On the contrary, I did not feel that my mind or conscious awareness was intervening at all; I was just letting myself give in to the process of discovery. As a matter of fact, when I was creating the image and even when it was finished, or when I decided to stop, I was not fully aware of the image I had created. It was not until I revisited the painting a day or two later that I realised what this image expressed—more than I had been able to express in words or even in thoughts to myself until then. The painting dealt with the feelings and events that had happened to me eight or ten years earlier.

Without this first stage, my own creative process as an artist might have stagnated or died. Discovering my capacity to escape within saved me in a way because it freed me to face the truth of feelings as yet unacknowledged. By escaping within I was able also to contain and even shield myself from the intensity of the feelings and memories until they could be transformed and absorbed. It was not until I made this work that my artistic energy returned to me. Until that point I had not produced any art for several years, despite my classical training. I was adapting to a new life in the States, a new language, a new culture, and struggling to make a living while raising a handicapped child. I think I was afraid of letting myself go through the process of grieving. At the time I was struggling to learn English, and, needless to say, I could not yet express my feeling or thoughts in English. And I think unconsciously I avoided creating art so I did not have to face the trauma I had endured. Creating art was and still is my best way of expressing my thoughts.

While preparing for this presentation, I had several conversations with a friend over a period of months where we discussed my creative process as well as my more traumatic experiences in the prisoner-ofwar camp (Figure 5). A rather significant instance of reverie occurred at our third meeting, which seems not unlike the experience an analyst and his or her client might share. Thinking about the story of how being an artist had made my time in the camp more bearable, a remarkable memory that I’d long forgotten or buried or repressed bubbled to the surface. And this powerful experience of accidentally bumping into one of the most meaningful moments of my life as an artist left me overjoyed and dumbfounded at the same time. I marvelled that I had recovered the memory and also that I had entirely forgotten the experience until this exchange with my friend. I want to share the story with you now because I believe it stands both as an example of the power of art to send others into reverie and as an example of reverie—in this instance, the meandering exchange with my friend—as a way to unlock more of the unknown aspects of our lives, both the traumatic and the beautiful aspects.

Figure 5. Sabah Al-Dhaher, Eyes through the Fence, 1998; oil on canvas, 4 × 6 inches. Collection of the artist.

While I was in the prisoner-of-war camp in the desert of Saudi Arabia in 1991, I had the opportunity to exhibit drawings that I had created during the first few months at the camp. When first at the camp, I had no access to pen or pencil, and although there was some cardboard from the food rations available, we would usually use this cardboard to make fires during the desert night for light, as well as to make some tea. In fact, for the first six months in the camp we had no electricity at all, so the only way to enjoy our evenings was to gather around fires outside our tents. This was our only reprieve from the heat beating down on our tents during the day.

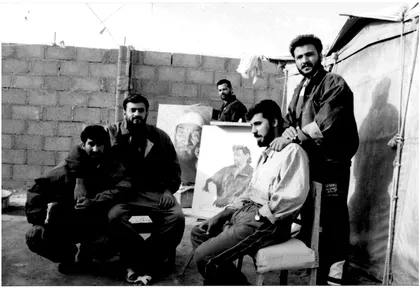

Eventually, one of the Iraqi prisoners in the block I was in, and who was a designated person to communicate on our behalf with the Saudi guards, was able to get me a pen when he heard I was an artist. I then started to collect any cardboard I could get my hands on and began to do some drawings, which were mostly of the faces of some of the prisoners. Within a couple of months, I must have made forty of these drawings (Figure 6).

The idea to exhibit these drawing came from the same prisoner who gave me the pen. Somehow he was able to convince the Saudi captain, who was in charge of ten different sections in the camp, to allow me to exhibit my drawings for my section, which housed about five hundred men. In total the camp held nearly ten thousand men. It was agreed that I could hang my drawings in the area between the inner and outer fences of our section of the camp. I created a kind of art gallery “wall” that ran a quarter of the length of one side of what was essentially a two-sided holding pen that enclosed our entire section, basically the size of a football field. The other nineteen sections within the camp were similarly designed. This ten-foot wide, double-fenced area was normally used to lock in the prisoners when the Saudi guards wanted to search the entire block—going through our tents and trashing everything in search of anything they deemed could be used as a weapon. It was some kind of psychological torture that they did often, mostly to keep us prisoners on our toes.

Figure 6. Sabah Al-Dhaher with friends, Rafha Refugee Camp, Saudi Arabia, 1992. Photo: Sabah Al-Dhaher. Pictured from left to right: Ali Jabbar, Jelil Abody, Hamid Alheyawi, Sabah Al-Dhaher, Rassul Madhkor.

So the idea to create an art exhibit in this same area and to open the inner gate of the camp and let the prisoners come to browse the exhibit freely was quite intriguing. And hanging the drawings on the same fence that we prisoners were usually required to keep a three-foot distance from at all times was incredibly exciting for me. I punctured holes in the corners of each drawing and with thread I tied the cardboard into the fence. The whole exhibit lasted for three hours, with all the prisoners coming freely from our section of the camp into this fenced perimeter area and then returning to the central area of our section once again.

About two hours into the exhibit, I looked up and saw two of the prisoners holding hands and talking while walking between the fences far beyond the exhibit area. In fact, they walked around the entire enclose...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PERMISSIONS

- ABOUT THE EDITORS AND CONTRIBUTORS

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER ONE Escape within

- CHAPTER TWO The primacy of reverie in making contact with a new couple

- CHAPTER THREE Come on—hold a baby's hand

- CHAPTER FOUR Reverie and the aesthetics of psychoanalysis

- CHAPTER FIVE From Fairbairn to the planet Neptune: reverie and the animistic psyche

- CHAPTER SIX The timing of the use of reverie

- CHAPTER SEVEN Infant observation as a pathway towards experiencing reverie and learning to interpret

- CHAPTER EIGHT The magnetic compass of reverie

- CHAPTER NINE The couple

- CHAPTER TEN Courage and sincerity as a base for reverie and interpretation

- CHAPTER ELEVEN Working with stone, working with psyche: the role of reverie in the process of making art and working with patients

- CHAPTER TWELVE Little Hans went alone into the wide world; or beta elements in search of a container for meaning

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN The spiral of transference: from mutative interpretation to reverie

- INDEX