eBook - ePub

Doing More Digital Humanities

Open Approaches to Creation, Growth, and Development

This is a test

- 334 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Doing More Digital Humanities

Open Approaches to Creation, Growth, and Development

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

As digital media, tools, and techniques continue to impact and advance the humanities, Doing More Digital Humanities provides practical information on how to do digital humanities work.

This book offers:

-

- A comprehensive, practical guide to the digital humanities.

-

- Accessible introductions, which in turn provide the grounding for the more advanced chapters within the book.

-

- An overview of core competencies, to help research teams, administrators, and allied groups, make informed decisions about suitable collaborators, skills development, and workflow.

-

- Guidance for individuals, collaborative teams, and academic managers who support digital humanities researchers.

-

- Contextualized case studies, including examples of projects, tools, centres, labs, and research clusters.

-

- Resources for starting digital humanities projects, including links to further readings, training materials and exercises, and resources beyond.

-

- Additional augmented content that complements the guidance and case studies in Doing Digital Humanities (Routledge, 2016).

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Doing More Digital Humanities by Constance Crompton, Richard J. Lane, Ray Siemens in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Library & Information Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Sustaining and growing

1

Legacy technologies and digital futures

Flossing my teeth. Wearing sunscreen. Going to the gym. Thinking of the long-term preservation of my digital projects. These are all things I should be doing, but I sometimes don’t quite get to. But I’m not in love with the idea of “shoulds” in the first place.

The start of every digital project is as exhilarating as it is overwhelming. But when should you start looking ahead to the end? And does there have to be an end? In this chapter, I’d like to consider some best practices for thinking about your DH project in the long term, from workflow and technologies to people and resources. I will share my experience on a long-standing existing digital project, The World Shakespeare Bibliography Online.

Like our hesitance to embrace should, I’d like us to question what it means to have a “best practice.”1 Each project is different; each researcher is different; there is no out-of-the-box solution that will work for everything. Rather than trying to tackle the (impossible?) task of outlining how to update and preserve all projects, in this chapter, I share what worked (and what didn’t) for the World Shakespeare Bibliography, in hopes that you will know how and when to ask the questions you need for your project to survive.

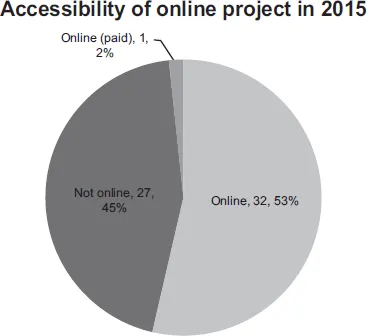

Survival for digital projects is an issue: a big, important, and looming issue. As Robin Camille Davis reports, 45% of projects discussed at DH 2005 are no longer available (see Figure 1.1); that is to say, almost half of the digital projects that were robust enough to be presented at an international digital humanities conference were lost just ten years later. The same loss rates do not hold true for print books. Even terrible books—which might sell poorly, be remaindered, and languish unread on bookshelves—don’t disappear in the same way as digital projects. In 2014, Jerome McGann, the pioneer of hypermedia and digital editions, said of his magnum opus, the Rossetti Archive, “I am now thinking that, to preserve what I have come to see as the permanent core of its scholarly materials, I shall have to print it out” (A New Republic 137). Archiving and other forms of future-proofing are important considerations, but they are not the thrust of this chapter. Here, I focus on a different kind of long-term planning: keeping a project alive and updated even after its creator, maintainer, or original visionary is no longer at the helm.

Figure 1.1 Robin Camille Davis, “Accessibility of online project in 2015,” an analysis of digital project availability from the DH 2005 conference (from “Taking Care of Digital Efforts”).

Source: Reproduced courtesy of the creator.

This chapter has three main sections: first, I discuss the exigence for thinking about long-term project planning; second, I turn to the recent World Shakespeare Bibliography update as a case study; and third, I outline some general principles for long-term project planning. In short, this chapter explores why we need to think about digital preservation, what it takes to migrate a project from legacy technologies, and how we can help secure futures for digital projects.

Bibliographies of online scholarly projects: why we need to think of digital futures

As Davis convincingly shows (see Figure 1.1), the loss rate for digital projects is high. When I consult bibliographies of early modern digital projects, this same rate is borne out across the subfield. To show how the loss of digital projects affects a specific field, in this case, the field of early modern literary studies, I turned to three bibliographies of early modern digital projects from 2001 and 2002: Robert C. Evans’s “Internet Resources for Teaching Early Modern Women Writers,” Georgianna Ziegler’s “Women Writers Online: An Evaluation and Annotated Bibliography of Web Resources,” and Lisa Hopkins’s “Shakespeare and the Renaissance on the Web.”

Of the 52 resources that Evans listed, 65% of the sites are now lost. Similar loss rates plague projects that Georgianna Ziegler discussed, which might be expected given the overlap in their coverage. Of the 35 sites Hopkins surveyed, 20 are still around (though seven have moved to new pages and cannot be accessed through the URLs that Hopkins cites and need to be found using a search engine). Fifteen of Hopkins’s surveyed sites, or almost half, are lost: this includes two sites that still exist but have changed their purpose. Items on Hopkins’s list had a slightly better chance of survival partly because she included major sites such as the Internet Movie Database (IMDB) that were not specific to early modern studies.

Of the websites listed by Evans, Ziegler, and Hopkins, those that still survive are more likely to be university affiliated and have a .edu domain. Unsurprisingly, websites that seem to have been maintained by an individual (for instance, on AOL) are less likely to still be around. Other still-extant websites include those affiliated with major institutions such as the Royal Shakespeare Company and Shakespeare’s Globe, although the latter is one of the sites that changed its domain name and so cannot be accessed with the URL described in Hopkins’s bibliography. Naturally, the sites for the Royal Shakespeare Company and Shakespeare’s Globe have been updated quite a bit in 10+ years since Hopkins pointed scholars to them: a visitor today will see vastly different content than a visitor would have a decade ago, but the sites still serve the purpose of providing information about these two cultural institutions. Other sites remain essentially the same as when they were described in 2001 and 2002, for better or worse. Susanne Weber’s 17th Century Women Poets is technically still a live website, but most of the links to the online poetry are broken—it remains useful primarily as a table of contents for an online anthology that no longer offers most of its texts. Some of the sites to which Weber points are still online but have simply moved or updated their URL structure, such as the University of Toronto’s Representative Poetry Online (ed. Plamondon, still currently updated). Others, like the Emory Women Writers Resource Project (ed. Cavanagh, updated 2006), exist but no longer have the content online that Weber points to, such as the works by Margaret Cavendish.

As 17th Century Women Poets demonstrates, hyperlinking can be one of the most important features of a digital project and also, in an ever-changing online landscape, one of the most challenging to maintain. Eduardo Urbino’s Cervantes Project is another site that is starting to falter: as of mid-2017, some images no longer load and functionality is being lost. 17th Century Women Poets is hosted by the University of Cologne; the Cervantes Project is based out of Texas A&M and the Universidad de Castilia-La Mancha. While institutional support might have led to the creation and decades-long existence of these sites, it has not guaranteed their continued survival and their full functionality. Both projects have, remarkably, existed for decades: the Cervantes Project since 1995 and 17th Century Women Poets since 1997; but their continued existence is not guaranteed.

The Geistesgeschichte der Renaissance: internet resourcen (GGRenir), cited by Evans, was particularly forthright about their inability to stay up-to-date. A banner displayed prominently across their homepage and in variations on different pages announces: “The GGRENir database, useful as it may be, has not been updated since sometime in 2003—as making new entries there and periodically updating existing entries takes more time than I have (and will have in the foreseeable future). Thus—unless someone or some institution provides us with considerable financial or other support for this—there will be no updates” (Kuhn, emphasis in the original). What does Heinrich Kuhn need to keep his resource working? Money and time. Anyone who has managed a digital project understands these needs.

While we can look at the state of digital projects as a binary, either still online or not still online (as in Figure 1.1), these early modern digital projects demonstrate that there is more of a continuum—and each part brings its own difficulties. If, as discussed earlier, a still-extant but not updated site causes difficulties, a site that is consistently updated can also cause challenges. Frequently updated sites might delete old material (as the Folger Shakespeare Library did in their 2016 site relaunch) or change their website structure, resulting in new URLs (as Representative Poetry Online did). Early discussions of these sites might quote altered or deleted texts or analyse now-lost functionality.

Although changing URLs can be a challenge, sometimes, ultimately, changing URLs can be in the best interest of a digital project. R. S. Bear’s site, Renascence Editions (cited by both Hopkins and Ziegler), offers an example of a successfully archived project that has moved. Initially, Renascence Editions appeared as part of the Early Modern Literary Studies Journal and was also mirrored through the larger Luminarium website. Anniina Jokinen’s Luminarium main site (cited by Hopkins, Ziegler, and Evans), a mainstay of online literary studies, hasn’t itself been updated since 2007. The EMLS-hosted Renascence Editions was last updated in 2007; the Luminarium Renascence Editions site’s last update was in 2009. This information would be more troubling if Renascence Editions had not been successfully archived by the University of Oregon libraries in 2004. The archived site is not quite as functional as the live webpages (for instance, the editions exist only in pdf and are not all visible from a single-page table of contents), but the digital archive preserves the materials, presumably for the long-term. In this case, changing the URL and slightly mitigating the functionality are certainly worth keeping this important site live.

Online journals offer a strong case study of the challenges of lost pages and broken links. Both Ziegler’s and Evans’s online bibliographies are full of links that no longer work; some of these could be fixed because they point to a site that has moved; others point to now-lost websites. By comparison, Hopkins’s printed bibliography, which is not available online, also gives now-broken web-links, but there is no way to update this without wholly rewriting and republishing her article. Furthermore, many links from websites to Ziegler’s bibliography itself (including those cited by Hopkins and Evans) result in an error, because the online journal Early Modern Literary Studies is no longer hosted with Sheffield Hallam University. Similarly, Evans’s bibliography is not findable through a simple Google search: searching for the title in quotation marks and his name (“Internet Resources for Teaching Early Modern Women Writers” Evans) brings up a single result in Google, and when you click through to it, it is the introduction to the issue of Working Papers on the Web in which his bibliography appears. This introduction page itself has no links to his article, to the journal homepage, or to the table of contents for the volume. Evans’s contribution now needs to be found by searching for the journal or altering the URL from the introduction to take you to the volume. Despite being university supported and having a legitimate editorial board, Working Papers on the Web is now defunct. But why do we care about an out-of-date bibliography in a defunct journal about inaccessible resources? Because this is the norm, not the exception.

Even maintaining lists of digital resources about a given topic takes work to maintain; it can provide an important service to the field. For instance, Mr. William Shakespeare on the Internet was a well-known site from Palomar College that offered a curated list of important digital resources for the study of Shakespeare. Now, when you visit the site, you see simply, “Mr William Shakespeare is now retired”—not coincidentally, the retirement of Mr. William Shakespeare coincided with the site’s creator, Terry A. Gray. Hopkins points to the University of Toronto’s Center for Reformation and Renaissance Studies website as one that offers a “list of electronic resources for research” (Hopkins 69); visiting their site now reveals no such list. Presumably, it was too much work to maintain an up-to-date overview of reputable sites related to Renaissance and Reformation studies.

Writing evaluative or analytic arguments about the resources in a given field is important work. Current scholars need these articles and bibliographies to introduce them to new resources, to updates to existing resources, and to ways of using digital resources and tools that they might not have considered. Future scholars will turn to articles that list or analyse current-at-the-time digital resources in order to discuss the state of the field at a given point, as I have here.

Evans correctly predicted that “almost by definition the Internet, and everything connected with it, is shifting and ephemeral. By the time this piece is electronically ‘published,’ many of the sites described in it will have changed in numerous ways, and some of them may even have disappeared.” Evans called for an “archival mega-site” that would preserve the sites he discussed. He did not know of the then-recently launched Wayback Machine from the Internet Archive, which is that “archival mega-site” he wished for—but it is not a complete archive and at times suffers from the same difficulties as the aging sites themselves, including broken links and lost functionality.

I argue that we need more lists of, articles about, reviews of, and bibliographies on digital projects, precisely because they document a rapidly changing field. The more detailed that each can be will make them more valuable: although listing URLs or simply providing a series of links is at least something, annotations or evaluative statements about digital projects will be of even more use. Archiving and maintaining digital projects is one step towards preservation: but to understand the nature of a given field, we need to continue the critical work we do as scholars and preserve not just individual projects but also a broader view...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of contributors

- Introduction

- Part I Sustaining and growing

- Part II Making

- Part III Learning

- Index