![]()

1

The Agricultural Age

The Achievements and Limitations of Several Millennia of World History

Here’s a clear challenge, closely linked to the problems with the concept of modernization discussed in the Preface: how can common features of major societies in the Agricultural Age be identified without blurring crucial regional and chronological differences into an overly simple sense of “traditional society”? For if we detach “traditional” features from the variety of actual social contexts, we will also distort the later treatment of industrial changes and their relationship to regional patterns and identities.

Agricultural societies could be intensely religious, or they could emphasize more secular values—though usually with some popular religious beliefs and possibly what some would call superstitions involved as well. They could be relatively prosperous, or they could be close to impoverished. They could sustain some vibrant cities or generate only a modest urban structure. They could embrace far-flung trade, or they could rely heavily on regional sufficiency. The range was considerable and really important.

Further, of course, agricultural societies could and did change over time. Substantial migrations brought new mixtures of peoples at many different points in time. Transregional trade levels tended on the whole to increase, and other adjustments might ensue—for example, in the expansion of leading cities. Artistic styles could shift in new directions, sometimes because of new religious commitments but for other reasons as well. Homosexuality, widely accepted in one agricultural society, might be rejected in its successor—as happened in the transition from the classical Mediterranean world to Christian Europe. Invasions—like that of European colonialists into the agricultural societies of Central America and the Andes after 1492—could provoke huge change. This chapter will focus on basic patterns, but these must not be seen as entirely static.

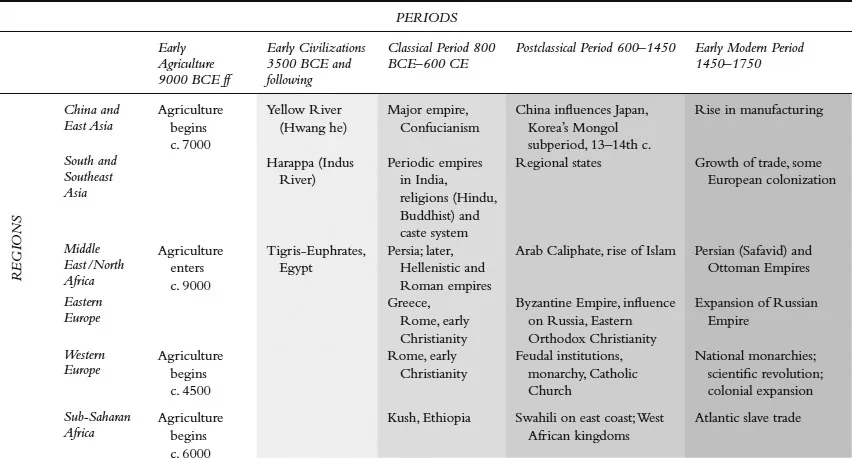

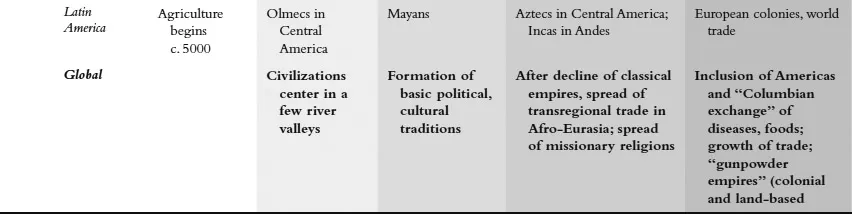

Table 1.1 outlines some of the most common divisions in the Agricultural Age, noting the time periods that many historians employ to capture particularly important and widely shared transformations during these long millennia. Major changes mark the advent of the classical civilizations, replacing river valley predecessors, and then the expansion of the world religions and new trading patterns after 600 CE. A final “agricultural” period, covering the three centuries after 1450, is actually a transition point, in which the pace of change accelerates. Table 1.1 also denotes the basic regions—defined by some combination of geography, shared culture, and shared historical experience—often used to highlight distinctive characteristics. Not surprisingly, both the chronological and the regional categories can be defined in different ways, so the chart is meant to be suggestive rather than definitive. But it clearly reflects the types of divisions most world history surveys introduce to the Agricultural Age—and some would prefer an even more detailed list of key regions and chronological subperiods.

TABLE 1.1 Periods and Regions in the Agricultural Age

Granting the frequent preference for considerable and varied detail, the fact remains that there are some common features in most of the societies the developed during the Agricultural Age, and arguably these deserve considerable emphasis in their own right. They must assuredly be presented in some explicit tension with variety and change. And the commonalities must not be pressed too far: in some key aspects of social life, there were in fact no overarching patterns, and where this was the case, the complexities must be clearly, if briefly, noted. The basic dynamics of the Agricultural Age shaped important directions in the human experience, but with some vital limitations.

The bulk of world history, as presented in most surveys including the leading textbooks, actually focuses on the Agricultural Age. At least two thirds of the coverage, after a brief bow to human origins and the original hunting-and-gathering economy, typically deal with the origins of agriculture, the formation of more complex societies, and then the history of major civilizations, religions, and interactions up to the 18th century, when industrialization first came into view. This is a rich panorama, involving a host of important regional details and chronological shifts over the span of up to 10 millennia. Yet—and here’s the presumptuous assertion—the details involved can obscure some fundamental dynamics—the features that virtually all agricultural societies had in common. And these are precisely the features we need to capture as a baseline for assessing what core changes industrialization would introduce.

The Rise of Agricultural Society

We can get a start on the fundamentals by suggesting how agriculture, wherever it emerged, differed from the hunting-and-gathering framework that had defined the human experience for so many thousands of years. Whether the focus is on the first conversion to agriculture, in the northern Middle East around 9000 BCE or its separate invention in south Asia two thousand years later or its independent emergence in Central America two millennia after that, agriculture had a number of common consequences.

A few initial examples: in hunting-and-gathering societies, small bands of humans—usually, no more than 40 to 80 per band—moved around periodically, at least over short distances, in search of game, plus nuts, fruits, and berries. Once agricultural societies were firmly established (there was often a transition period), the vast majority of the population had become farmers. Even the most advanced agricultural economy required eight farmers per 10 people overall, and commonly the ratio was higher still. Further, with a few exceptions, farming populations usually settled down; among other things, when they began to clear forests for farmland, they reduced hunting opportunities, which could confirm the need to make local agriculture as productive as possible. The advantages of staying in one place surpassed the attractions of movement, though there were some complicated tradeoffs, including much greater vulnerability to invasion and war. Finally, communities expanded. Most peasant farmers lived in villages for mutual assistance and protection. Villages in turn could range from 400 to 600 people to several thousand. But the key point was, in contrast to hunting and gathering, human agglomerations became larger and more complex, almost certainly requiring different kinds of cultural rules and informal governance.

The contrast is clear: agriculture transformed the standard human occupation; it replaced movement with an emphasis on settlement; and it replaced small hunting bands with larger and in some ways more challenging social groupings. It also, particularly for men, required more effort. Hunters-gatherers often worked only a few hours a day. Agricultural labor varied seasonally, of course, but it required more effort on average.

The shared features of agricultural society—and far more will be listed as this chapter progresses—moved to a further level when the advent of complex societies, or civilizations, is added in. It is important to note that not all agricultural societies made that shift: for example, some parts of West Africa long featured a flourishing agricultural economy without formal states or the other apparatus of civilization. In most places, however, beginning around 3500 BCE in the Tigris-Euphrates valley of present-day Iraq, agriculture would generate or impose this additional apparatus.

The advent of greater social complexity in many agricultural regions involves a short list of crucial innovations, shared by almost all agricultural civilizations whether they copied each other or created independently. First, these societies had organized states, with at least small bureaucracies—rather than more informal patterns of leadership, they had a clear ruler or ruling body. Second, these societies began to form cities (though a few centers might develop in advance of full complexity), which meant they also promoted somewhat higher levels of trade (for cities could not exist without some exchange with the surrounding countryside). The cities were usually small, and they never embraced more than a modest minority of the population—but they existed, and their influence often outstripped their size. Finally, agricultural civilizations had writing, vital for record keeping both for governments and for merchants and requiring at least a modest educational system (to teach a few people to write). Only Inca civilization, of the major complex societies, managed to flourish without writing.

In discussing the features of agricultural civilizations, then, we focus on societies and regions in which most people had become farmers, living in settled villages that had outstripped purely family organization, and in which established governments, urban activity, and at least limited literacy sat atop the rural structures.

The final preliminary point about the Agricultural Age and the complex societies that emerged within it involves their slow but inexorable spread to additional parts of the world. Agriculture itself originated in a few discrete spots and fanned out from there. It did not necessarily spread rapidly: contacts among regions were limited and slow, but beyond this there were many good reasons for hunting-and-gathering people to prefer their own ways—and in a few small spots of the world, they still do. Agriculture involved not only substantial change but more work and more exposure not only to attack but to disease. It had one transcendent advantage: it provided a food supply, if sometimes a meager one, that could support a much larger population (and so permit larger families and, probably, more sexual activity). So it did have attractive powers. Further, agricultural people themselves might migrate in response to crowding, bringing their new patterns with them and forcing them on others. Recent discoveries suggest that this was how agriculture reached Western Europe, about 6,500 years ago: not by example or persuasion but by the arrival of farmers from the northern Middle East, who simply took over the show. Other migrations—for example, the great Bantu migration from west-central Africa to the south and east—had similar impact in spreading agriculture.

Then came the apparatus of agricultural civilizations. Historians debate whether farmers set up governments voluntarily or whether powerful warriors compelled them to accept their leadership: probably a bit of both in some cases. Civilizations, and particularly governments, could help agricultural people deal with the threat of invasion by providing some formal military protection. They could also assist in resolving disputes: even hunters-gatherers faced conflicts in their groups, which might lead to murder, and agricultural people developed commitments to property in land that could generate even more friction. Governments, providing law codes and some system of judicial courts, might defuse tensions: all early governments, for example, worked hard to offer mechanisms that would bypass private family feuds or revengeful violence. But governments, headed by ambitious rulers, might force acceptance as well—whether people wanted them or not.

Whatever the balance, agricultural civilizations spread aggressively, bringing writing, governments, and more trade and cities to other regions. The early river-valley civilizations thus fanned out, embracing larger territories like the Middle East or, a bit later, the whole of China. By the 16th century the expansion of later agricultural states, like Russia or the Ottoman Empire, brought the apparatus of agricultural civilization to Central Asia, where nomadic societies had long flourished without formal governments. Colonization efforts from Western Europe had the same impact on North America (as well as taking over Central American and Andean civilizations in the Americas): agriculture and civilization spread out even more broadly.

Already by 1450, the basic forms of agricultural civilizations embraced east, south, and southeast Asia with only pockets of exception, as well as the Middle East and North Africa; they prevailed in Europe; they were standard in West Africa and the African Indian Ocean coast and were spreading more widely in the subcontinent; and they flourished in the two major centers in the Americas. By 1750, when the Agricultural Age began to draw to a close, the forms had advanced in other parts of Asia and the Americas and were about to enter Australia. Discussion of the key features of the Agricultural Age, by this point, is a discussion of virtually the whole world, with only a few holdouts for alternative options.

The Characteristics of the Agricultural Age

Standard features of agricultural societies spilled over into many domains of human endeavor. Not surprisingly, the most definite and widely shared attributes were those closest to the production of food (which is what most agricultural people focused on) and related activities. Arguably, these same attributes involve some of the most fundamental aspects of human life—including birth and death. As we range farther from these arenas, for example, into the realm of political structures, we will face both greater variety and more potential for debate. In the sections that follow, correspondingly, we move from clear-cut near-uniformities to more complicated (though not more important) realms, with areas for discussion or uncertainty explicitly indicated.

Population, Food, Disease, and the Environment

Agricultural societies fairly quickly developed a signature population structure, markedly different from that of their hunting-and-gathering predecessors. The structure had a variety of ramifications, particularly on the major age groups. It reflected the greater capacity of agricultural society to support a comparatively large population—but also some important constraints—and the new uses that were found for children. Many of the basic features of agricultural life flowed from and sustained the new demographic model.

Birth rates rose with the advent of agriculture, initially generating substantial population growth. Average family size would quickly double. There were about 10 million humans scattered in small bands around the world before agriculture first emerged. Over the next millennia, this figure would surge past 100 million. People were clearly taking advantage of agriculture’s capacity to provide food for a larger number, and of course, the gradual spread of this production system only advanced the process.

Yet agriculture involved a bit of a balancing act in terms of population structures. Families and whole societies needed substantial numbers of children. Most village farms operated on a family basis, with children providing a vital part of the labor force. Too few children could be a devastating problem. The same held for whole societies, and leaders realized that a vibrant population structure was important for the economy and for military recruitment. Childless couples might be denounced, as in an Egyptian criticism of a scribe who had not done his duty: “You are not an honorable man because you have not made your wives pregnant … As for the man who has no children, let him obtain an orphan and raise him.” In China, men with sufficient property were encouraged to take an additional wife or concubine if an initial partner did not produce offspring. And where the couple was infertile (a problem far more commonly, and unjustly, blamed on women than on men), the family did often hire the children of others to help out with the work. Not surprisingly, agricultural families paid careful attention to their childrearing potential, often seeking magical or other cures for infertility.

On the other hand, too many children were also a threat. For the family, it was easily possible to have more children than the available land or craft operation could support. For society as a whole, population pressure could lead to social unrest. At several points in Chinese history during the Agricultural Age, population growth outstripped available land, pushing peasants to rebellion against their landlords and, on occasion, against the state. In Western Europe by the 14th century, population had reached or surpassed the level that current agriculture could sustain, again leading to riots and a period of demographic stabilization. In many cases, of course, population pressure also generated further migration into less populated areas, sometimes overwhelming local inhabitants.

For families, the goal was sufficient children to provide necessary labor and assure family continuity as property passed to the next generation—but not too many. Six to eight children per family was the average during the Agricultural Age. This was well above the three to four children born in hunting-and-gathering families but noticeably below human potential: for a fertile couple producing offspring with no restraint will typically generate 14 to 15 babies between puberty and menopause. Six to eight children, by contrast, was compatible with approximate stability with a small growth potential. Between 30 and 50% of the children would die, usually before age 2, so the family would expect only three to four offspring to reach adulthood. Since about 20% of the population would be infertile for biological reasons—with some families, as a result, requiring help from the children of others—the stability goal was indeed attainable.

But approximate stability meant some method of controlling births. Various agricultural societies experimented with natural substances to prevent pregnancy or induce abortion; animal intestines were sometimes used as condoms. There was, however, no general or reliable method of contraception. Typically, mothers would nurse newborns for up to 18 months—though this was far less than had been the case in hunting-and-gathering groups; prolonged lactation reduced the chances of a new pregnancy. And many peasant couples simply abstained from sex, particularly as they reached their 30s or early 40s, at least in part to keep the birth rate down: though it was not uncommon deliberately to seek one final child right before menopause, hoping that the individual would be around to help care for the couple as they aged. Even these precautions, however, might not suffice. Individual families were often overburdened with children—a key cause of poverty either for the whole family or for the extra children who would have nothing to inherit.

In this setting, where the desired balance was not easy to achieve, other features were common. Many agricultural societies designated small groups of people who were supposed to remain celibate, most commonly for religious reasons. Wealthy families, during the Agricultural Age, typically had larger numbers of children than ordinary peasants and workers could afford, again a sign of the tight link between birth rate and economic resources. At various social levels, in a number of agricultural societies, infanticide was also widely practiced: parents would frequently abandon an unwanted infant (most commonly a female infant, viewed as less useful to the family), leaving it to die. The practice was widespread in Greece and Rome and in classical China. Newer world religions, like Islam and Christianity, worked effectively to reduce infanticide, but it probably still occurred; and some parents, leaving unwanted infants to the care of religious institutions, continued to seek a similar result.

The balancing act—the need for substantial numbers of children but not too many—was a crucial feature of human demography during the Agricultural Age. But this feature should not obscure the other main point: most agricultural families had large numbers of children, even if not (they almost certainly hoped) the maximum possible. Bearing and caring for six to eight children was an overwhelming fact of life for many women. Villages and towns were filled with children. Up to 41% of all people in a typical agricultural community were under the age of 14; some of course would soon die, but even so the child focus of the community was virtually inescapable. A huge amount of adult effort—for only 54% of the typical population was aged 15 to 59—simply went into providing for the offspring, with some help from the children themselves.

Agricultural societies might continue to generate some population growth, even after the initial spurt when the production system was first adopted. World population by 1000 CE had reached 250 million—a 40% increase over the levels 1,500 years before; and it would reach 382 million by 1400. At the same time, both famine and disease served as checks against more rapid growth. Localities typically suffered some food shortage every seven years or so because of weather conditions or crop failure. Epidemic disease was an even greater problem, particularly as trade increased am...