- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Models Of Cognitive Development

About this book

In spite of its obvious importance and popularity, the field of cognitive development remains highly fragmented due to the vast diversity of models of what knowledge and reasoning are, and how they develop. This new Classic Edition of Models of Cognitive Development aims to overcome this barrier through its careful introduction, illustrated examples, and approach to helping students think more critically about the subject.

In this significant work, Richardson provides students, researchers, and comparative theoreticians with a cohesive understanding of the area by organizing diverse schools, frameworks, and approaches according to a much smaller set of underlying assumptions or preconceptions, which themselves can be historically interrelated. By understanding these, it's possible to find pathways around the area more confidently as a whole, to see the "wood" as well as the theoretical trees, and be able to react to individual models more critically and constructively.

The Classic Edition of this core text will be essential reading for undergraduate and graduate students of cognitive development.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Nativist models

Introduction

Contemporary nativism

Natural mechanics and natural computations

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface to the classic edition

- Preface

- 1. Nativist models

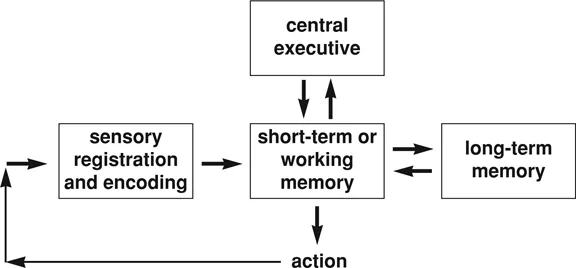

- 2. Associationist models

- 3. Constructivist models

- 4. Sociocognitive models

- 5. Models mixed and models new

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app