eBook - ePub

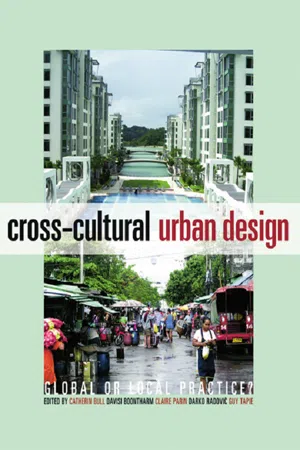

Cross-Cultural Urban Design

Global or Local Practice?

This is a test

- 269 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cross-Cultural Urban Design

Global or Local Practice?

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Unprecedented in its scope, Cross-Cultural Urban Design: Global or Local Practice? explores how urban design has responded to recent trends towards global standardisation. Following analysis of its practice in the local domain, the book looks at how urban planning and design should be repositioned for the future. It looks at: population movement urb

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Cross-Cultural Urban Design by Catherin Bull,Davisi Boontharm,Claire Parin,Darko Radovic,Guy Tapie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Reconceptualizing the City

Introduction

New Ways to Read Difference

The concept of ‘local identity’ and the issues with which it presents urban planners and designers in the face of globalizing trends towards standardization and homogenization are central to the debates about the future city included here. At the same time, the concept of local identity is subject to diverse definitions and interpretations. Can it usefully be generalized to guide future practice? And if so, how? What indeed does local identity mean, and how is it manifest?

What the exchanges presented reveal is that while objective criteria about what local identity is here, or there, cannot be generalized across urban territories and domains, not, the processes that manifest as a particular culture, space and place can, with analysis, be better understood. Analysis of the processes by which culture manifests as space and place can usefully inform practice, but many presumptions about how global forces appear superficially to standardize and homogenize and may not be based on fact. Understanding how local culture works, how it produces space and values it, and why, yields some surprising outcomes.

Local Identity: A Subjective Value?

The very idea of the local identity of a place seems to be essentially subjective, intrinsically linked to whoever describes it, and unable to be dissociated from the cultural context from which it emerges. Such a subjective, even sentimental position is somewhat paradoxical given the objective orientation that legitimates much contemporary discourse. Such a position recalls the ambiguity noted by Alois Riegl (1903) at the beginning of the twentieth century concerning the concept of ‘ancientness’ – a quality that has proved particularly effective in promoting the preservation and conservation of material elements of cultural heritage able to be identified by specialists as worthy of preservation.

Indeed in Der moderne denkmalkultus, Riegl argued that contrary to the notions of historical and artistic value that lay within the realms of proven knowledge, the value of ancientness was associated with the need of individuals to be attached to forms and objects that acted as material witnesses to the past, especially in a world of accelerated change, a world where the concept of time is becoming increasingly abstract.

Similarly, today, in the postmodern era where the mobility of people and the communication of information seem destined to develop without limits, it appears that in whatever cultural context, there is even more demand for material reference points that provide continuity with past times. This suggests that the question of retaining local identity in a globalizing world is central to the design of local space and place. It seems however, to be a question that is beyond answering effectively within the practical and symbolic value systems that usually apply in the production of contemporary urban projects.

To the urban professionals who contribute here, however, the design and delivery of local or everyday space, needs to meet increasingly complex functions, and abstract demands. Such projects, for example, are meant to communicate significance in the global domain and to contribute to an ensemble of sites that are landmarks, identifying territory. Technical expertise must be supplemented by expertise in expressing identity using many different scales, from the local to the global.

The contributors not only discuss their experiences in understanding how local identity in urban form is created, lost or eroded, they also discuss similar processes relating to local ecological systems under threat from development driven by the global economy. Local culture, built systems and landscapes, all appear to be undergoing systematic exploitation by development activities, specifically tourism, whose impacts are especially pervasive, perhaps because it is an industry whose very survival, paradoxically, appears to rely on the confluence between local identity and global accessibility. Such concerns are, however, coupled with an emerging recognition and acceptance that territories and cultures should be, to some degree, protected from intrusions. Inevitably they will change and evolve into completely new forms that articulate the evolving relationship between ubiquitous global forces, and local capacities to express the particularities of their culture in the process of transformation.

This evolution signals the importance of reflection on, and debates about, experiences of process among urban professionals – the process of project delivery; the process of conserving or developing urban precincts, places and territories; and the dynamic between global and local forces through time, manifest as space and place. Encouraging reflection and reflective practice in Donald Schon’s (1983) terms, on the dynamics and interdependences inherent in contemporary practice, internationally and across cultural domains, seems essential if urban designers are to mediate between the competing demands they confront on a daily basis in their work.

While a common definition of local identity cannot be drawn from these exchanges, nor a common methodology for its protection or construction, lessons can be learnt. The very idea of local identity – its importance in the process of transformation – needs to be explored. Sharing the experience of many professionals internationally, as these cases do, paves the way for reconceptualizing urban design, and enabling it to better confront this predicament.

Learning to Read Difference

What is revealed by these reflections is the variety of methods used to read the culture and form of the various territories, and to represent their distinctiveness in the face of trends towards methodological as well as formal standardization. The three cases reported by French and Thai contributors propose as many methods. While all places were responding to what could be considered standard processes of urbanization, the methods of response varied according to the particular dynamics of culture, form and development process.

Sani Limthongsakul, in Chapter 1 ‘Finding the identity of place through local landscapes: Mooban and Kampong’, investigates vernacular space in the context of the rural village before modern development. Using methods derived from the anthropology of space, she identifies the spatial system that regulates land use, landscape and built form at the scale of that territory in order to make plain the values that are the basis of its identity as a place. She explores the relationship between underlying land form, spatial arrangement and use that is contingent on the complex cultural and religious demands that operate there. The village economy and its social relations contribute to the conservation of its social and environmental equilibrium. The analysis reveals the overlap of different layers of socio-spatial organization and their interdependence, making this landscape particularly sensitive to intrusion by other ways of life and urban forms. Equally however, her work exposes the availability of an underlying social structure of real robustness.

Sidh Sintusingha, in Chapter 2, ‘Erasure, layering, transformation, absorption. The convergence of formal traditions’, explores how new values become integrated in the Thai landscape across territories where urbanization is well established. He highlights the shifts in meaning that accompany the evolution of landscape, the architectural and urban forms as they are transformed under the influence of external (global) and local forces. The concept of the ‘cultural landscape’ becomes the medium through which to explore the complexities of the evolution of space at sites where standard forms of urban development (the urban park and the resort enclave) are appropriated and reinterpreted as new forms of local space. In these examples they become layered with elements of local meaning, resulting in complex hybrids that combine both local and global forms, and reveal much about how transformation is actually occurring.

The third contribution selected is that of Xavier Guillot, Chapter 3, ‘Between “asianization” and “new compolitanism”. Housing in twenty-first-century Singapore’. Like Sintusingha, Guillot analyses the continuing process of localization of global concepts – in this case the imported concept of the residential estate, first in the form of the suburban villa and latterly in the form of the condominium. The condominium becomes the particular medium of change in an environment already at an advanced stage of urbanization. The discussion shows the significance of the design of the residential estates in communicating local identity and supporting modes of local living.

Although these analyses deal with contexts that are already in the process of urbanization to varying degrees, and the contributions hail from such different domains, the motivations for and ways of reading both the spaces and the processes of transformation have many points in common.

First, within the frameworks of their analyses, the contributors attach importance to the relationship between built and landscape form in the urban domain. They also place importance on the kinds of activities that these domains support, suggesting these as authentic expressions of local culture, even when they manifest local responses to global trends (tourism for example). They call upon broader concepts of landscape as the means to establish the link between place as it is perceived by its inhabitants, and space as an objective reality. Landscape becomes the means to establish the characteristics that are most particular to the milieu.

Second, common to the different methodological approaches is their focus on territorial scales that attract their interest. The authors consider these as epitomizing certain types of social practices (Limthongsakul), ways of producing or transforming space (Guillot), or expressing the dynamic equilibrium between collective practices, representation and spatial production (Sintusingha). All aim at defining local space in both its physical and cultural dimensions, using methods of analysis based on shared knowledge at a global level (universal concepts of time according to Claude Levi-Strauss), historical representations of spatial production according to Frampton (1983). Such analyses across space illuminate the process of change insofar as they allow, at each territorial scale and in each location, knowledge about the characteristic way spaces change in contemporary times, and the role of local actors in that process.

Defined like this, such analyses suggest two ways of conceptualizing the processes of transformation and acculturation now underway, that manifest as change to urban environments. The first relates to the way urban fabric is renewed or remade and the level of resistance to change inherent in spatial structures, forms and local society. The second relates to the way that existing urban forms, models or ways of thinking at the scale of the local milieu can be adapted and assimilate ‘the new’ or different. Such observations suggest new lines of enquiry and research that will question the way local specificities should be approached, and what actually constitutes difference. Indeed they suggest that beyond observation of what exists here or there, the real issue is the resilience or robustness of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Illustration credits

- List of contributors

- Foreword: confronting epistemes

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: cross-cultural practice – why experiment now?

- Part 1: Reconceptualizing the city

- Part 2: Experiments in practice

- Part 3: Learning cross-cultural practice

- Index