eBook - ePub

The Growth Strategies of Hotel Chains

Best Business Practices by Leading Companies

This is a test

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

How did Accor, Cendant, Choice Hotels International, Marriott, and Hilton become the largest hotel chains in the worldand what strategies will they use to continue their growth?This first-of-its-kind textbook presents a balanced overview of the theory and practice of hotel chains' growth strategies. It explains in-depth how

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Growth Strategies of Hotel Chains by Kaye Sung Chon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Hospitality, Travel & Tourism Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Chapter 1

The Concept of a Strategy

What is a strategy? No definition is universally accepted. The term is used by many authors with different meanings. For example, some include targets and goals as part of the strategy, while others establish clear distinctions between them.

James Brian Quinn (Mintzberg and Quinn, 1993) gives special emphasis to the military uses of the word, and he highlights a series of “dimensions” or criteria from this field that are crucial if strategies are to be successful. To illustrate these criteria, the writer refers to the times of Philip II and Alexander of Macedonia, the origin of his main example. Quinn also presents a summarized theory of how similar concepts to those used then influenced subsequent military and diplomatic strategies.

No one can deny that the military aspects of strategy have always been a subject of discussion and part of our universal literature. In fact the origin of the word “strategy” goes back to the Greeks who were conquered by Alexander the Great and his father.

Initially the word strategos was used to refer to a specific rank (the commander in chief of an army). Later it came to mean “the general’s skills,” or the psychological aptitude and character skills with which he carried out the appointed role. In the time of Pericles (450 BC), it referred to administrative skills (management, leadership, oratory, and power), and in the days of Alexander the Great (330 BC) the term was used to refer to the ability to apply force, overcome the enemy, and create a global, unified system of government.

Mintzberg concentrates on several different definitions of strategy, as a plan (i.e., a maneuver), pattern, position, and perspective (Mintzberg and Quinn, 1993). The author uses the first two definitions to take readers beyond the concept of a deliberate strategy, moving far away from the traditional meaning of the word to the notion of an emerging strategy. With it, Mintzberg introduces the idea that strategies can be developed within an organization without anyone consciously proposing to do so or making a proposal as such. In other words, they are not formulated. Although this seems to contradict what is already established in published literature on strategy, Mintzberg maintains that many people implicitly use the word this way, even though they would not actually define it so.

In the world of management, a “strategy” is a pattern or plan that encapsulates the main goals and policies of an organization, while also establishing a coherent sequence of actions to be put into practice. A well-formulated strategy facilitates the systemization and allocation of an organization’s resources, taking into account the organization’s internal strong points and its shortcomings so as to achieve a viable, unique situation and also to anticipate potential contextual changes and unforeseen action by intelligent rivals.

Even though each strategic situation is different, do some common criteria tend to define what makes a good strategy? Simply because a strategy has worked, it cannot be used to judge another. Was it the Russians’ strategy in 1968 that enabled them to crush the Czechs? Of course other factors (including luck, abundant resources, highly intelligent or plainly stupid orders or maneuvers, and mistakes by the enemy) contribute toward certain end results.

Some studies propose certain basic criteria for assessing a strategy (Tilles, 1963; Christenson, Andrews, and Bower, 1978). These include a clear approach, motivating effects, internal coherence, contextual compatibility, the availability of the necessary resources, the degree of risk, coherence with key managers’ personal values, a suitable time frame, and applicability. Furthermore, by looking at historic examples of strategy from military, diplomatic, and business scenarios, we can infer that effective strategies must also include a minimum number of other basic factors and elements, such as These fundamental aspects of strategy apply, whether we are talking about business, government organization, or military campaigns.

- clear, decisive objectives;

- the ability to retain the initiative;

- concentration;

- flexibility;

- a coordinated, committed sense of leadership;

- surprise; and

- security.

Chapter 2

Competitive Strategies

The Theory

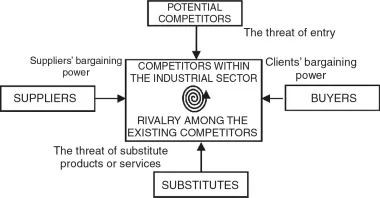

Porter suggests that generic competitive strategies are based on what he calls the factors that determine competition or, in other words, based on an analysis of the competitive environment. He comments that the competitive situation of a specific industrial sector depends on five fundamental competitive forces (Porter, 1982):

- The threat of new entry by potential competitors

- The threat of substitute products or services

- Clients’ bargaining power

- Suppliers’ bargaining power

- Rivalry among the current competitors

Figure 2.1 shows the different forces that affect competition in an industrial sector.

These five competitive forces together determine the intensity of competition and the profitability of the industrial sector. The strongest force (or forces) is the one that heads the field, and it plays a crucial role in the development of a strategy.1

Porter (1982) describes a competitive strategy as taking offensive or defensive action to create a secure position in an industrial sector, so as to deal successfully with the five competitive forces, thereby obtaining greater company returns on the capital invested.

Business managers have discovered many different ways of achieving this goal and, on an individual level, the best strategy is a unique formula that reflects the company’s specific circumstances. However, on a wider level, three internally consistent generic strategies can be identified and analyzed. These can be used singly or in combination to create a long-term secure position and distinguish the firm from rivals operating in the same sector.

Figure 2.1. The Forces That Affect Competition in an Industrial Sector

Several methods can ensure that an effective strategy achieves this secure position, thus protecting the company against the five competitive forces. They include (1) positioning the company so that its capabilities offer the best defense against the existing competitive forces; (2) influencing the balance of these forces via strategic movements, thus improving the business’s relative position; and (3) anticipating and responding swiftly to changes in the factors on which these forces depend, then choosing a strategy more consistent with the new competitive balance before rivals see this possibility.

An important aspect of an analysis of Porter’s competitive strategies (1982) is the value chain. With it, company leaders should be able to identify what activities they can influence in order to bring about one of the proposed competitive strategies. From a definition of what a competitive strategy is, an analysis of the five competitive forces or factors that determine competition, and the idea of a value chain, three generic competitive strategies can be described: cost leadership strategy, differentiation strategy, and focus or market niche strategy.

The first two strategies are suitable for rival companies competing in an entire sector or industry, whereas the third is appropriate for companies competing in a particular segment of an industrial sector or market.

Figure 2.2 shows these generic competitive strategies.

Cost Leadership

With a cost leadership strategy, the idea is to gain a competitive edge by achieving a cost advantage. In other words, you must reduce your costs as much as possible. This gives the company an advantage over its rivals and also over its suppliers and clients. To develop this strategy, several conditions are required:

- The company must have a high market share so that it has a high volume of sales. In this way the managers can benefit from learning and experience.

- The leaders must ensure the high performance of those factors that permit a reduction in the unit cost of production.

- Technology must be used to ensure that goods are made at the lowest possible cost.

- If possible, the company managers must try to carry out a policy of product standardization to achieve high production levels and, therefore, a lower unit cost.

Entry barriers are one way of contributing toward the strategy’s success, in the form of economies of scale and a cost advantage in production and distribution. This strategy allows a company to achieve a stronger position than its rivals, because the company’s low costs allow executives to cut prices while continuing to make a profit until their closest rival’s profit margins disappear. The company’s wider margins and greater size allow for bargaining with suppliers so that, even if the latter were to force a price increase, the company would still have a cost advantage.

Figure 2.2. The Three Generic Strategies

Nevertheless, this strategy has risks. If it is followed consistently but measures are not taken to guarantee the continuance of the previous conditions, serious dangers could arise. As changes in technology occur, the firm’s technology and production levels must be adapted to respond to new requirements. Should this not happen, the company could lose its cost advantage if a rival incorporates these changes instead.

Neither should the company leaders disregard their products’ possible obsolescence or clients’ new expectations. In addition, the strategy’s2 drawbacks also include the limited validity of the experience curve when a big change occurs in technology or when new entrants are able to learn more swiftly.

If company owners wish to achieve a cost advantage by reducing their total costs, an activity analysis can be very effective. It highlights activity-generated costs, activity components, and links between activities and chains of suppliers or clients that can be modified in order to contribute toward a decrease in costs.

The Differentiation Strategy

The aim of the differentiation strategy is to ensure that either the company in general or certain specific elements (such as its products, customer care, quality, etc.) are perceived to be unique by both clients and suppliers. As one might suppose, this kind of strategy means that the company involved must have certain capacities and skills (i.e., technology, marketing, etc.) that enable it to achieve, maintain, and develop a certain degree of differentiation.3

As for the clients, this strategy attempts to instill a sense of client loyalty toward the company and its products and services, making the demand less sensitive to price fluctuations. Differentiation permits higher prices and wider margins than companies without it could allow themselves. In turn, these wider margins help to ensure better bargaining power over suppliers and clients. Although exceptions exist, using this type of strategy normally makes it difficult to achieve a high market share.

The value chain is equally useful in the differentiation strategy. In this case, an analysis must be made of the activities involved in the value chain and their links in order to determine which of their basic characteristics can be modified so as to differentiate the company from its competitors.

The Focus or Market Niche Strategy

The focus or market niche strategy is based on the concept of concentrating on a certain segment of the market, thus limiting the scope of competition. Once a company is positioned in a market niche, the executives must try to achieve a position of leadership by cutting costs, by differentiation, or by both means, thereby trying to obtain a competitive advantage within the market segment or niche in which they are competing.

Com...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1. The Concept of a Strategy

- Chapter 2. Competitive Strategies

- Chapter 3. Diversification versus Specialization

- Chapter 4. Vertical Integration

- Chapter 5. Horizontal Integration

- Chapter 6. Diagonal Integration

- Chapter 7. Acquisitions and Mergers

- Chapter 8. Strategic Alliances: The Case of Joint Ventures

- Chapter 9. Franchise Contracts

- Chapter 10. Management Contracts

- Chapter 11. Leaseholds and Ownership

- Chapter 12. Branding

- Chapter 13. The Internationalization-Globalization

- Notes

- Bibiliography

- Index