This is a test

- 138 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Lao She's Teahouse and Its Two English Translations: Exploring Chinese Drama Translation with Systemic Functional Linguistics provides an in-depth application of Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) to the study of Chinese drama translation, and theoretically explores the interface between SFL and drama translation.

Investigating two English translations of the Chinese drama, Teahouse (?? Cha Guan in Chinese) by Lao She, and translated by John Howard-Gibbon and Ying Ruocheng respectively, Bo Wang and Yuanyi Ma apply Systemic Functional Linguistics to point out the choices that translators have to make in translation.

This book is of interest to graduates and researchers of Chinese translation and discourse studies.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Lao She's Teahouse and Its Two English Translations by Bo Wang, Yuanyi Ma in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Mapping and approaching Systemic Functional Linguistics and translation

In this chapter, we first situate the present study in Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) by introducing the historical background and the status quo of applying SFL to translation in Section 1.1. In Section 1.2, we offer a brief account of Teahouse (茶馆), a Chinese drama written by Lao She, which is regarded as monumental work in the history of Chinese literature. We then discuss our classification of the three kinds of text in Teahouse. Section 1.3 presents the research methods, elaborates on the analytical framework, and discusses the data size.

1.1 Systemic Functional Linguistics and translation

The past 50 years have witnessed the rapid development of Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), a theory that approaches language from various dimensions and understands language in context rather than in isolation (see Halliday 1985a, 1994a; Halliday & Matthiessen 2004, 2014 for SFL descriptions of English grammar). Unlike Chomsky’s (e.g. 1957, 1965, 2006) formal approach to language, according to which theory is isolated from application, SFL is an appliable theory that is not only designed to be applied but also remains in constant dialogue with application (Halliday 1985b, 2008; Matthiessen 2014a). This distinction between the functional approach to language and the formal approach is characterized as “ecologism” versus “formalism” in Seuren (1998) or “language as resource” versus “language as rule” in Halliday (1977).

Halliday (1964, 1985b) regards his theory of language as essentially consumer-oriented and admits that the value of a theory lies in its application. Consequently, SFL has been applied to different areas of language sciences including translation (Matthiessen 2009; see Wang & Ma in press for a detailed survey of this area). Systemic functional linguists view translation as a relation between languages, as a process of moving from one language to another, and as recreation of meaning in context. Halliday (2009) regards translation as a specialized domain, because relatively few formal or functional linguists have paid explicit attention to translation. He also recognizes translation as a kind of testing ground, and argues that a theory is inadequate if it “cannot account for the phenomenon of translation” (ibid.: 17). One prerequisite for applying SFL to translation is that SFL provides a theoretical basis of language description, with English, Chinese and various languages being described from the SFL perspective (e.g. Caffarel, Martin & Matthiessen 2004; Martin, Doran & Figueredo 2019; see Mwinlaaru & Xuan 2016 for an overview of this area).

The origin of applying SFL to translation, according to Steiner (2005, 2015, 2019), can be traced to the early British contextualism, i.e. Malinowski’s (e.g. 1923, 1935) anthropological studies on context and translation on the Trobriand Islands in Papua New Guinea. Malinowski (1935) emphasizes the role that translation plays in understanding an aboriginal language. He holds that translation is crucial in bringing out the differences between the meanings in some other cultures and his own English-speaking culture. Different from the missionary linguists’ Eurocentric view of translation that tries to assimilate the foreign culture into the target culture, Malinowski’s approach (1935) acknowledges the role that the context of culture plays by recognizing the differences between the source culture and the target culture. Malinowski’s (e.g. 1923, 1935) notion of context was inherited by Firth, who influenced Halliday and SFL.

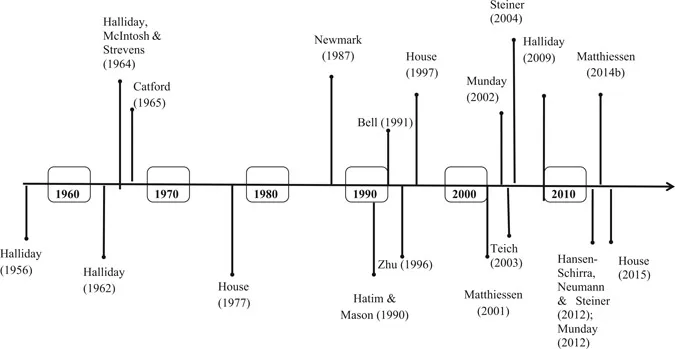

Figure 1.1 is a timeline that highlights some important studies of applying SFL to translation, reflecting the chronological development of theorizing and modeling translation from the SFL perspective. In accordance with Halliday’s (2001) characterization of translation theories, these studies in the timeline are descriptive rather than prescriptive, and can be considered as linguists’ theories of translation rather than those of translators.

Figure 1.1 A timeline of some important studies that apply SFL to translation

1.1.1 Early studies before the 1970s

Translation has been on the agenda of SFL since the 1950s, marked by Halliday’s (1956, 1962) engagement with machine translation in his early career. Halliday (1956) highlights the importance of linguistic analysis, states the futility of oneto-one translation equivalent, and emphasizes the need for describing the languages involved in machine translation. In this work, we find the initial ideas of SFL, such as (i) the paradigmatic organization in language description by regarding lexis as a resource and (ii) the notion of making choices in a thesaurus, which is capable of providing the different options available and is different from a dictionary. In his next paper on machine translation, Halliday (1962) applies his scale and category theory to machine translation, involving the grammatical categories of “level,” “unit,” “structure,” “form,” and “rank.” He relates translation equivalence to the rank scale of lexicogrammar, and distinguishes three steps in the process of translation:

First, there is the selection of the “most probable translation equivalent” for each item at each rank, based on simple frequency. Second, there is the conditioning effect of the surrounding text in the source language on these probabilities: here grammatical and lexical features of the unit next above are taken into account and may (or may not) lead to the choice of an item other than the one with highest overall probability. Third, there is the internal structure of the target language, which may (or may not) lead to the choice of yet another item as a result of grammatical and lexical relations particular to that language: these can be viewed as brought into operation similarly by step-by-step progression up the rank scale.

(Halliday 1962: 153)

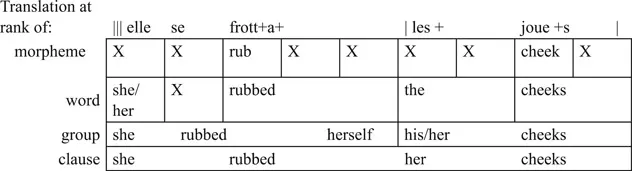

A follow-up work in this area is the chapter titled “Comparison and Translation” by Halliday, McIntosh and Strevens (1964), in which they discuss the relationship between language comparison, translation, and language teaching. They ground translation in language description and comparison, which include the following three steps: (i) the separate description of related features of each language, (ii) the establishment of comparability, and (iii) the comparison itself. Also, they apply the linguistic descriptions of stratum and rank in translation. Figure 1.2 shows how translation equivalence can be maintained at different ranks of lexicogrammar when translating from French to English. At the clause rank, translation equivalence is the easiest to achieve; thus, it is appropriate to translate the clause in French into one in English, as the clause rank is the widest grammatical environment where the text is maximally contextualized and where there is a higher degree of grammatically specified translation equivalence (see Matthiessen 2001). By contrast, at the rank of morpheme, equivalence is the most difficult to achieve, with only equivalent choices of two French morphemes – “frott” and “joue” being found in English. However, by moving upward along the rank scale from morpheme to clause, we find more equivalent choices between the two languages.

Figure 1.2 Multilingual correspondence and rank

Source: Adapted from Halliday, McIntosh & Strevens (1964: 127)

The overall application continues with Catford (1965), who formulates a general theory of translation based on Halliday’s (1961) scale and category grammar – an early version of systemic functional grammar. In Catford’s (1965) monograph, translation equivalence and translation shift are examined from the perspectives of rank and stratification (termed as level, which include context, form: grammar and lexis, and substance: graphology or phonology). Catford (1965) takes the search of translation equivalents in the target language as the crucial issue of translation practice and regards the nature and conditions of translation equivalence as the critical task of translation theory.

1.1.2 Studies from the 1970s to the millennium

From the late 1960s to 1980s, Halliday (1961) increasingly focuses on the paradigmatic system, thus treating the syntagmatic structure as the realization of the choices made in the system. Semantics, along with lexicogrammar, is considered as a stratum of the content plane. Also, the three metafunctions, i.e. the ideational, the interpersonal, and the textual, are identified and dealt with at the level of semantics and lexicogrammar (Halliday 1967a, 1967b, 1985b). Along with the developments in SFL, House (1977) proposes her model of translation quality assessment during the latter half of the 1970s. Based on the equivalence between the source text and the target text, her model remains one of the most influential frameworks to translation criticism. Conceiving translation as recontextualization, House’s (e.g. 1977, 1997, 2015) model heavily depends on the Hallidayan analysis of field, tenor, and mode. Lexicogrammatical analysis is also incorporated, which is regarded as realizations of register and genre. House’s model provides theoretical motivations for two translation strategies, i.e. overt translation and covert translation. The concept of the cultural filter, which captures the sociocultural differences, is also hi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations and symbols

- Abbreviations for interlinear glossing

- 1 Mapping and approaching Systemic Functional Linguistics and translation

- 2 Reenacting interpersonal meaning in dramatic dialogue

- 3 Re-presenting textual meaning in dramatic monologue

- 4 Reconstruing logical meaning in stage direction

- 5 Analyzing field, tenor, and mode: perspectives from context

- 6 Conclusion: toward a systemic functional account of drama translation

- References

- Index