![]()

Part I

____________

Critical Foundations

![]()

1

A New Hegemony

The Rise of Neoliberalism

Chapter Overview

At this point, you might have a sense of what neoliberalism is, but you’re probably still fuzzy on the details. This chapter starts to clear things up by charting the making of our neoliberal conjuncture. By tracing the history and development of neoliberalism, we will learn how competition came to be the driving force in our everyday lives. Specifically, we will examine the rise of neoliberal hegemony in four phases.

Table 1.1 Four Phases of Neoliberalism Phase I | 1920–1950 | Theoretical innovation |

Phase II | 1950–1980 | Organizing, institution building, and knowledge production |

Phase III | 1980–2000 | Crisis management and policy implementation |

Phase IV | 2000—Present | Crisis ordinariness and precarity |

As we will see, neoliberalism is far from natural and necessary; rather, it represents a clear political project that was organized, struggled for, and won.

A New Hegemony

We begin our investigation with a historical account of the rise of neoliberal hegemony. Hegemony is a concept developed by Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci. Gramsci was keen to account for the definitive role that culture played in legitimizing and sustaining capitalism and its exploitation of the working classes. In our own context of extreme economic inequality, Gramsci’s question is still pressing: How and why do ordinary working folks come to accept a system where wealth is produced by their collective labors and energies but appropriated individually by only a few at the top? The theory of hegemony suggests that the answer to this question is not simply a matter of direct exploitation and control by the capitalist class. Rather, hegemony posits that power is maintained through ongoing, ever-shifting cultural processes of winning the consent of the governed, that is, ordinary people like you and me.

In other words, if we want to really understand why and how phenomena like inequality and exploitation exist, we have to attend to the particular, contingent, and often contradictory ways in which culture gets mobilized to forward the interests and power of the ruling classes. According to Gramsci, there was not one ruling class, but rather a historical bloc: “a moving equilibrium” of class interests and values. Hegemony names a cultural struggle for moral, social, economic, and political leadership; in this struggle, a field—or assemblage—of practices, discourses, values, and beliefs come to be dominant. While this field is powerful and firmly entrenched, it is also open to contestation. In other words, hegemonic power is always on the move; it has to keep winning our consent to survive, and sometimes it fails to do so.

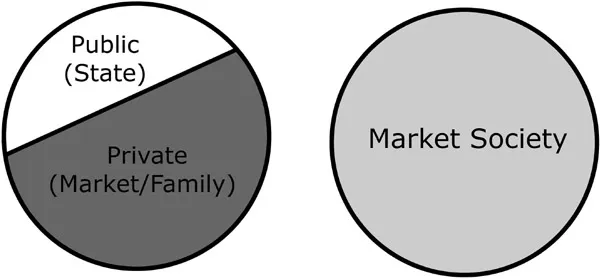

Through the lens of hegemony, we can think about the rise of neoliberalism as an ongoing political project—and class struggle—to shift society’s political equilibrium and create a new dominant field. Specifically, we are going to trace the shift from liberal to neoliberal hegemony. This shift is represented in the two images below.

Previous versions of liberal hegemony imagined society to be divided into distinct public and private spheres. The public sphere was the purview of the state, and its role was to ensure the formal rights and freedoms of citizens through the rule of law. The private sphere included the economy and the domestic sphere of home and family. For the most part, liberal hegemony was animated by a commitment to limited government, as the goal was to allow for as much freedom in trade, associations, and civil society as possible, while preserving social order and individual rights. Politics took shape largely around the line between public and private; more precisely, it was a struggle over where and how to draw the line. In other words, within the field of liberal hegemony, politics was a question of how to define the uses and limits of the state and its public function in a capitalist society. Of course, political parties often disagreed passionately about where and how to draw that line. As we’ll see below, many advocated for laissez-faire capitalism, while others argued for a greater public role in ensuring the health, happiness, and rights of citizens. What’s crucial though is that everyone agreed that there was a line to be drawn, and that there was a public function for the state.

As Figure 1.1 shows, neoliberal hegemony works to erase this line between public and private and to create an entire society—in fact, an entire world—based on private, market competition. In this way, neoliberalism represents a radical reinvention of liberalism and thus of the horizons of hegemonic struggle. Crucially, within neoliberalism, the state’s function does not go away; rather, it is deconstructed and reconstructed toward the new end of expanding private markets. Consequently, contemporary politics take shape around questions of how best to promote competition. For the most part, politics on both the left and right have been subsumed by neoliberal hegemony. For example, while neoliberalism made its debut in Western politics with the right-wing administrations of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, leaders associated with the left have worked to further neoliberal hegemony in stunning ways. As we will explore in more depth below and in the coming chapters, both U.S. presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama have governed to create a privatized, market society. In other words, there is both a left and a right hegemonic horizon of neoliberalism. Thus, moving beyond neoliberalism will ultimately require a whole new field of politics.

Figure 1.1 Liberal vs. Neoliberal Hegemony

It is important to see that the gradual shift from liberal to neoliberal hegemony was not inevitable or natural, nor was it easy. Rather, what we now call neoliberalism is the effect of a sustained hegemonic struggle over the course of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries to construct and maintain a new political equilibrium. Simply put, neoliberalism was, and continues to be, struggled over, fought for, and won.

In Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics, Daniel Stedman Jones charts the history of the neoliberal project in three phases. The first phase saw the development of neoliberal ideas and philosophies in Europe during the years between World War I and World War II, as a relatively small group of economists (including most notably those from Austria, Germany, and France), wrestling with the rise of fascism, communism, and socialism, sought to envision a new liberal society that would protect individual liberties and free markets. The second phase was a period of institution building, knowledge production, and organizing that enabled neoliberalism to cultivate a powerful base in culture and politics, especially in the U.S. and United Kingdom. During this phase, neoliberalism developed into a “thought collective” and full-fledged political movement. In the third phase, neoliberal ideas migrated from the margins to the center of political life as they came to shape global trade and development discourse, as well as the politics of powerful Western democracies. As suggested by the theory of hegemony, none of these phases were neat and clean; each was shot through with struggle and contingency.

I am adding a fourth phase, which is the focus of this book. Here neoliberalism is not only a set of economic policies and political discourses, but also a deeply entrenched sensibility of who we are and can become and of what is possible to do, both individually and collectively. It is what Raymond Williams called “a structure of feeling.” Thanks to a convergence of different social, economic, and cultural forces, which we will explore throughout the following chapters, competition has become fully embedded in our lifeworlds: it is our culture, our conjuncture, the air we breathe. More specifically, this fourth phase is characterized by widespread precarity, where crisis becomes ordinary, a constant feature of everyday life. As we will learn in coming chapters, we are prompted to confront the precarity neoliberalism brings to our lives with more neoliberalism, that is, with living in competition and self-enclosed individualism.

Phase I: Theoretical Innovation

The Crisis of Liberalism and the Birth of the Social Welfare State

Neoliberalism emerged out of the crisis of liberalism that ultimately came to a head in the early twentieth century. It is crucial to understand that liberal hegemony was never a coherent, unified phenomenon. Rather, it developed around a central political antagonism. On one side were those who championed individual liberty (especially private property rights and free markets) above all else. They argued against government intervention in private life, especially in the market. On the other side, social reformers believed that government should be pursued for the common good and not just for individual liberties. In the decades leading up to the Great Depression, it became clear that the individual-liberty side, which had long been dominant, was inadequate for managing huge transformations in capitalism that were underway. These transformations included industrialization, urbanization, and internationalization, as well as the rise of large-scale corporate firms that squeezed smaller market actors. Huge gaps formed between the political-economic elite, the middle classes, and the poor. Simply put, liberalism was in crisis.

During this time of social, cultural, and economic upheaval, those espousing the common good gained political ground. Specifically, the misery and devastation of the Great Depression solidified the gains for social reformers, opening a new era where a new, common-good liberalism began to prevail. In the United States, President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration passed a comprehensive set of social policies designed to protect individuals from the unpredictable and often brutal operations of capitalism. These included the following:

- Reforming banking: The Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 set up regulatory agencies to provide oversight to the stock markets and financial sector, while enforcing the separation of commercial banking and speculative investment. Simply put, banks couldn’t gamble with your savings and future.

- Strengthening labor: In 1935, the National Recovery Administration and the National Labor Relations Act were passed to recognize labor unions and the rights of workers to organize. At the same time, the administration spurred employment through the Public Works Administration, the Civil Works Administration, and the Works Progress Administration, while guaranteeing workers a dignified retirement with the Social Security Act of 1935.

- Promoting housing: A range of programs, policies, and agencies were established, including the Federal Housing Administration and the U.S. Housing Authority, to encourage homeownership and provide housing to the poor and homeless.1

Taken together, these policies marked the birth of the so-called social welfare state, albeit one that was limited in scope and often highly exclusionary in practice. For example, a universal health care program was never realized. Many social groups, including African-Americans, migrant farm workers, and women, were prohibited by law from receiving federal benefits such as social security or unemployment.2 Additionally, institutional racism plagued (as it still does) housing and banking institutions.

The Walter Lippmann Colloquium and the Birth of Neoliberalism

It is helpful to trace the emergence of our neoliberal conjuncture back to this moment where the common good was starting to win the day via the establishment of a limited and exclusionary social welfare state. For, despite the fact that these social welfare policies effectively “saved” capitalism from destroying itself, the individual-liberty side was deeply troubled. They feared that a new hegemony was on the rise, one that represented a threat to their core values of individual liberties, private property, and free markets. To the individual-liberty side, all of these social policies and demands smelled a lot like socialism, and they were determined to combat them with a new liberal hegemony of their own. So, in 1938, American author and political commentator Walter Lippmann organized a gathering of twenty-six leading liberal thinkers in Paris to discuss and debate the fate of individual-liberty liberalism in the current context. In addition to Lippman, key players included leading Austrian economists Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises, French intellectuals Louis Rougier and Jacques Rueff, and German economists Alexander Rüstow and Wilhelm Röpke.

The term neoliberalism was originally coined here at the Walter Lippmann Colloquium and referred to a new form of individual-liberty liberalism that was at once anti-common good and anti-laissez-faire. It is so important to see that this new form represented a key theoretical and political innovation. For, in previous versions of individual-liberty liberalism, laissez-faire was dogma: the only way to protect private property and market freedom from the state was to limit the powers of the state. Neoliberalism flipped the script by imagining an active, interventionist state actively working not in the interests of the common good, but in the interests of free markets.

While neoliberals agreed generally on the need for this “new” liberalism, they were not so united on what these new modes of state intervention on behalf of markets should look like. Some neoliberals (including Von Mises and Hayek) remained radically individual-liberty-orie...