So you’re an engineer or a student preparing to enter the profession. In any case, you’re already busy. Your first question could be whether learning to write well is really worth much care and effort. We think it is. After all, an engineer who writes poorly might just

1. struggle and waste time;

2. disappoint or annoy important people like professors, mentors, supervisors, colleagues, and customers;

3. fail to complete a crucial document such as a thesis, dissertation, technical report, or technical proposal;

4. fail to get hard-won technical ideas across to others;

5. suffer from career stagnation or failure to land an attractive job;

6. alienate customers or lose contracts;

7. become ensnared in a lawsuit; and possibly

8. acquire a negative reputation as a poor communicator.

In short, a poor writer may have a second-rate engineering career. An ability to write professionally is a required part of being professional.

1.2 Think, Then Write, Like an Engineer

As engineers, we write primarily to communicate our thoughts rather than, say, our emotions or poetic sense. This is not to say that technical writing must be robotic or sterile. Like completely dry meat, completely dry text can be hard to chew. It’s great if passion for a subject comes through in writing. But the primary goal of technical writing is not to communicate emotion. We want to tell our readers what, where, when, why, and how. So our writing should represent our thought. Like it or not, people judge us by the quality of our writing. We cannot be everywhere, but our writing can be (and, as a result of the Internet, likely will be). It could surely outlive us, acting as a helpful resource for — or a perplexing annoyance to — subsequent generations of engineers. We want our writing to be good.

What counts as “good” writing in an engineering context? This question will be addressed throughout the book. It is worth stating at the outset, however, that we will keep the needs and purposes of the reader firmly in mind at all times. We will have to consider the reader: his or her background, goals and purposes, etc. We are writing to inform a certain target audience, not just to fill pages with words, equations, and diagrams. On the other hand, we are not aiming for “perfection” (whatever that is). We are simply trying to do a job with our writing and to do it well. Standard engineering design processes do not produce perfect switches or pulleys, and sound writing processes do not produce perfect documents. Intelligent compromise is basic to all practical engineering activity.

Engineers exist under constant pressure to be productive. They’re expected to tackle large tasks, often with little guidance. A writing project can be such a task.

It’s time for Ken, a graduate student in mechanical engineering, to start writing his graduate thesis. Ken has a solid understanding of his research but is unsure how to plan a document of this magnitude. As the weeks pass, Ken begins to worry that he has writer’s block.

Suppose we face a hefty writing project such as a doctoral dissertation, technical report, or research proposal. How do we get started and stay on track? This question will also be addressed throughout the book. The good news is that writing can come naturally to engineers if they keep their task in an appropriate mental framework. We have found the standard engineering design process to be an excellent framework to use.

Dr. Smythe, Ken’s thesis advisor, reminds Ken that he’s an engineer and that time is money. The grant under which he’s being supported has deadlines for certain deliverables, and one of those is a report based on Ken’s thesis. Writer’s block is not an option. The professor also reminds Ken that the very word engineer is derived from the Latin word for ingenuity. This switches Ken into more of an engineering mode: “I have a big problem to solve here. That problem involves writing, but it’s still a problem and engineers are trained problem solvers. What do I know about problem solving, in general?” His next thought is “How could I design a document to solve my problem?”

Ken is on the verge of a realization. With engineering design concepts, he can tackle a huge writing project and do it well. First, however, Ken must adapt what he knows about design to the writing task.

1.3 Quick Review of Some Design Concepts

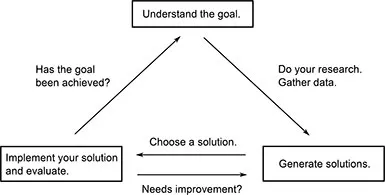

The engineering design process is often depicted as a flowchart. Figure 1.1 shows the main stages in the process. They are

1. Understand the goal.

2. Do your research. Gather data.

3. Generate solution alternatives.

4. Choose a solution to pursue.

5. Implement your solution and evaluate it. Improve it if necessary.

These steps can be adapted to virtually any formal technical writing task.

A pyramid of three boxes showing the continuous loop of the design process. The design flow starts at the top box marked “understand your goal” and proceeds to the bottom right box marked "generate solutions." This box interacts bidirectionally with the box on the bottom left marked "implement your solution and evaluate." The loop closes by returning to the top box from the bottom left.

After reviewing the design concepts cited above, Ken responds by drafting a plan as follows.

1. Understand the goal. Ken must produce a graduate thesis that is acceptable to his advisor and his examination committee.

2. Do your research. Gather data. Ken must clearly understand the problem he faces. He must learn what a graduate thesis is. Who is the typical audience for a thesis? Is there a deadline for his final submission and defense? Ken must put all of his materials in order. These include the results of his initial literature search, his theoretical work and predictions, descriptions of his experimental setups and preliminary results, and his tentative conclusions. He knows that his research may not be complete; further experiments are needed, and the results of these may necessitate more theoretical work. However, he was told to begin thinking about the thesis, so he responds by planning to gather what he currently has available. Realizing that there are probably format requirements for something as important as a graduate thesis, Ken decides to seek a list of official guidelines from his university.

3. Generate solutions. Ken will have to develop a set of alternative approaches to writing his thesis. At this point, a major question is how the thesis should be organized at the chapter level. Rather than planning to generate just one possible response to this question, Ken follows the standard design process and plans to generate two possible chapter schemes. He hopes a conversation with his thesis advisor will assist him in choosing one of these schemes, combining the strengths of both schemes into a new scheme, or abandoning both schemes in favor of a third scheme he hadn’t thought of yet.

4. Choose one solution to pursue. For Ken, this choice will be heavily influenced by discussion with his advisor — a primary “customer” his final “design” must satisfy.

5. Implement the chosen solution, evaluate it, and refine it if necessary. Ken understands that this is where much of his work will lie. He will have to write, solicit feedback from others, evaluate their comments, rewrite, try to obtain feedback again, and so on.

By adapting Figure 1.1 to his purposes, Ken has progressed far beyond merely getting started — he has generated a roadmap for himself. By following this map, he will avoid getting lost somewhere in the daunting process that stretches into the weeks and months ahead. Ken knows that at some point, if he persists, he will see the light at the end of the tunnel. It will be time to put the finishing touches on his document and arrange an opportunity to defend its contents before the graduate committee.

As an engineer, you can adapt your writing tasks along these lines. Whether you’re writing a proposal, a report, or even a doctoral dissertation, a design-based approach will help you start a project, write more efficiently, and finish the task faster and with better results. Let’s delve more deeply into some of the fundamental aspects of the design process.

Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches

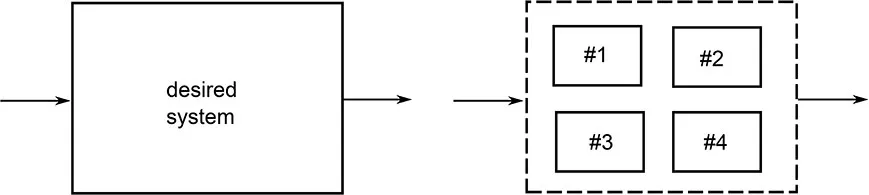

Given a design task, we may decompose it into subtasks and, in turn, further reduce the subtasks to any desired level of decomposition. This idea is the basis of the top-down design approach (Figure 1.2).

A large box on the left represents the desired system. An arrow points to a large box on the right that is subdivided into four smaller boxes. These boxes are labeled #1, #2, #3, and #4.

One might take a desired electrical system and break it down into subsystems such as a microcontroller, a sensor, an actuator, and a power supply. The power supply, in turn, might be decomposed into a rectifier and a filter, and so on. Lower level subsystems are then designed and assembled into subsystems at the next higher level until the system is complete. This approach — analysis followed by synthesis — is advocated as an engineering design approach and clearly applies to the design of large, formal documents.

The heart of Ken’s research is an intricate experimenta...