On Megastructure Approaches

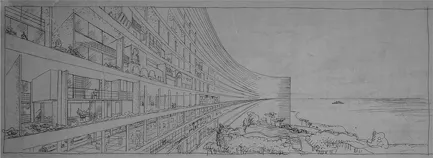

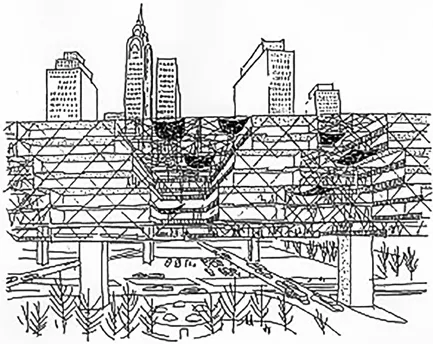

Reyner Banham’s book titled Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past is the most comprehensive survey of Megastructure approaches.1 In order to understand the origin of the concept, Banham first clarified the major characteristics of Mega-structure in the coexistence of a “monumental, supporting frame” and “habitable containers”.2 Then through the investigation of similar projects from urban history, he searched for the ancestors of Megastructure that already contained the basic idea in an embryonic stage. Among the candidates, Banham considered Ponte Vecchio in Florence (Figure PI.1) to be the very first precedent, because of its vast multilevel structure, which accommodated various urban facilities in a temporary setting. As for the “true ancestor of megastructure”,3 in turn, he noted Corbusier’s Plan ‘Obus’, 1931 (Figure PI.2) already had a clear distinction between the vast permanent structure and the inhabited housing units. In spite of the similarities, however, Banham after all doubted that these ancestors could be seen as immediate and conscious adaptations for the Megastructure, because—he claimed—“the word to focus the concept did not exist until 1964”.4 On a search for the real forces that facilitated the formation of the Megastructure concept, Banham focused on the “insoluble problem of the modern city”5 represented in the dissolution of its sense “as a physical artifact”6 among various other factors, and traced it back to the inefficiency of social and statistical planning procedures in that epoch.7 He also referred to a common ‘faith’ of contemporary architects in the possibility of solving the problem through the Megastructure, based on its original idea of “city as a single building”8 that implies the potential to “bridge the gap between the single building

Figure PI.1 Ponte Vecchio, Florence.

Figure PI.2 Le Corbusier, Plan ‘Obus’, 1931.

and its disintegrating urban context”.9 In other words, Banham suggested that the Megastructure approach is better understood as an attempt to link individual buildings to the city. Based on this understanding, he next focused on finding the first Megastructure that was consciously designed, and presented several candidates from the early 1950s up to the early 1960s. Among the candidates, he first mentioned

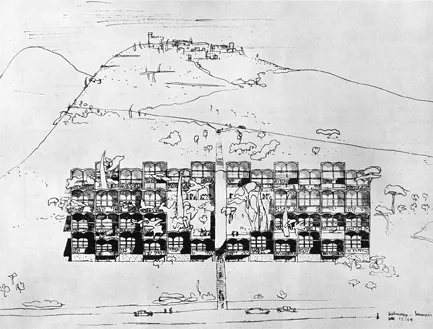

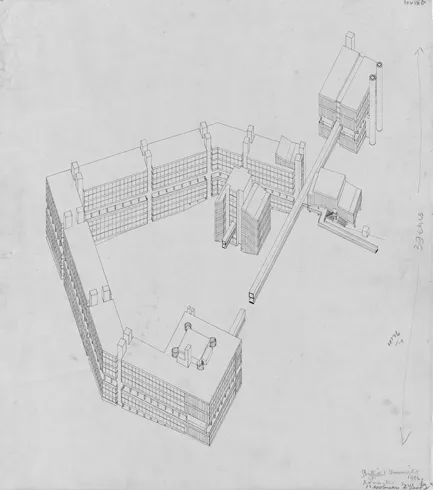

Figure PI.3 Le Corbusier, Roq et Rob Project, 1948.

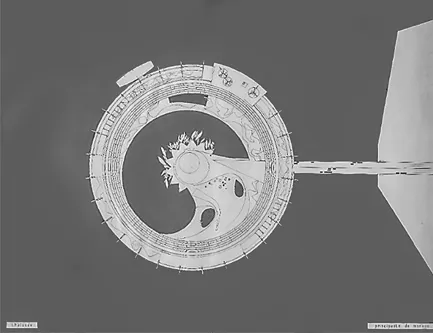

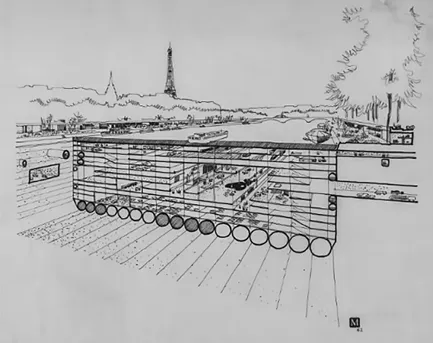

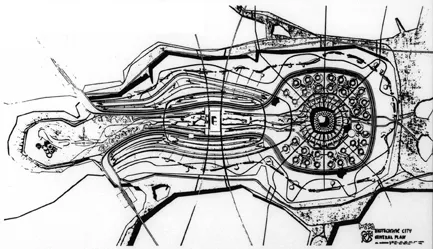

Corbusier’s Roq et Rob Project, 1948 (Figure PI.3) and Sheffield University Competition, 1953 (Figure PI.4) by Smithsons and James Stirling, but finally excluded them, saying that they lack a “substantial permanent structure on which the modular and repetitive dwelling units are built up”.10 Following chronological order to summarize Megastructure approaches, Banham next referred to the Japanese Metabolism movement, because of the group’s inevitable primacy in both the idea and design of the Megastructure, considering “megastructure as a unique Japanese contribution to modern architecture”.11 In his evaluation, Kikutake’s Marine City (Figure PI.5) is “one of the prime visions of the Metabolist group”,12 and Tange’s MIT Boston Harbor Project, 1959 (Figure PI.6) stands as “the first real megastructure”,13 while A Plan for Tokyo, 1960 (Figure PI.7) is considered “the most heroic vision of town planning to appear in this century”14 that contained the Megastructure on various scale levels. However, there is no mention of their formal characteristics. On the other hand, Banham considered the Megastructure of the French spatial urbanism movement as “the most abstract, least material and most conventionally elegant”15 among all Megastructure visions. Based on his evaluation, the potentiality of the group can be seen in the structural inventions, including the concept of a “three-dimensional planning grid”16 and the “obsessive diagonalism”17 of the structure, which served as precedent for a succession of Megastructure projects. Among the

Figure PI.4 The Smithson and James Stirling, Sheffield University Competition Design, 1953.

members of the group, Banham regarded Yona Friedman as the most remarkable character, whose system of “space-frames-in-the-air”18 (Figure PI.8)—which is also based on the concept of the three-dimensional planning grid—shows striking resemblances to the large governmental and administration buildings supported from a vertical core system at the center of Tange’s plan for Tokyo. At the same time Banham saw a similar Metabolist influence on Paul Maymont’s Floating Island Project, 1963 (Figure PI.9) as well as his City Under the Seine Project, 1962 (Figure PI.10). Subsequently, regarding the Italian Cittá-territorio movement Banham focused on the two leaders: Paolo Soleri and Manfredo Tafuri. While he considered Soleri the

Figure PI.5 Kiyonori Kikutake, Marine City Project, 1963.

Figure PI.6 Kenzo Tange, MIT Boston Harbor Project, 1959.

Figure PI.7 Kenzo Tange, A Plan for Tokyo, 1960.

Figure PI.8 Yona Friedman, ‘Space-frames-in-the-air’, 1960–62.

Figure PI.9 Paul Maymont, Floating Island Project, 1963.

Figure PI.10 Paul Maymont, City under the Seine Project, 1962.

most well-known Italian Megastructuralist through his ‘Mesa City’ Drawings, 1960 (Figure PI.11) and pointed out his influence on the utopian visions by Archigram seen in the use of a diagonal frame, he evaluated Tafuri as the spiritual force of the movement.

Figure PI.11 Paolo Soleri, ‘Mesa City’ drawings, 1960.

Before introducing the British Megastructure movement that entirely differs from other Megastructure approaches because of its “science-fiction fantasy”,19 Banham broke the thread of the chronological overview in order to discuss the concept of utopia. He saw the reason for neglecting Megastructure approaches in their common misinterpretation as utopia due to a rigid distinction between the vision of the city as a single work of imagination and the completed works. Instead, he suggested a distinction between two kinds of utopias, which sharply differ from each other in their original concept: the one “obsessional about the real social system, but not too concerned about architectural form”20 as a ‘real utopia’ and the other purely based on “architectural adventurism”21 and rather called ‘ideal’. From this distinction, Banham reconsidered Megastructure projects as “ideal models for future cities”.22 At the same time, he located the British Megastructure movement among modern planning utopias,23 which are based on the concept of a “‘mobile leisure population’ as the point of departure for the modeling of the town-planning future”.24 As for the first representation of their concept, he pointed out that Cedric Price’s Fun Palace, 1962 (Figure PI.12) can be considered the ancestor of Archigram projects. Among the various futuristic visions by Archigram, he set off Peter Cook’s Plug-In City, 1963–4 (Figure PI.13)—the most well-known of Archigram projects—and evaluated it mainly for the use of a diagonal frame.25 He also noted the influence of Archigram proposals on Megastructure projects in Italy and Japan.26

Figure PI.12 Cedric Price, Fun Palace, 1962.

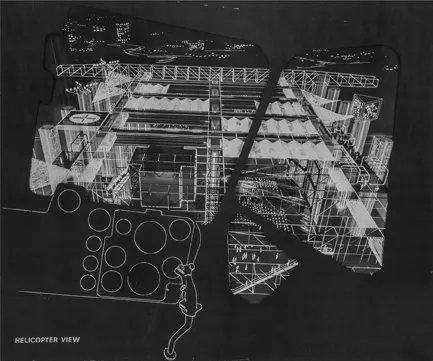

While chronicling the Megastructure movement, Banham put special emphasis on two dates. One is 1964, which he called a “megayear”27 not only because the term first appeared in print at that time but also because it was the year for Archi-gram to make its debut and for most of the actually built Megastructures to be designed. The other is 1967, which was the year of the Montreal Expo, the most extensive display of Megastructure projects, and the completion of Cumbernauld New Town Centre, which Banham evaluated as “the most complete megastructure to be built”.28 After presenting some more built examples of the Megastructure, including the application of its concept to university campuses as test models for cities, Banham turned back to the question of motives behind Megastructure attempts. Although he raised some more options, such as the nostalgia of architects for a past “and a hypothesized future”29 or the intention to create a kind of visual order to make cities architecturally comprehensible,30 in the end he left the question open.

Altogether, Banham’s book is better understood as an attempt to chronicle the movement by tracing the for...