- 154 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book is a great resource for people who enjoy polyhedra, symmetry, geometry, mathematics and origami. The types of models presented are similar in nature to the models in Mukerji's Marvelous Modular Origami, but some of the chapters are more advanced and all of the designs are new. The reader can learn about polyhedra while making these models and is left with the ability to design one's own models. Step-by-step folding instructions for over 40 models are presented. Although the book is for intermediate folders, beginners are encouraged to try because origami basics are explained. The diagrams are easy to follow and each model is accompanied by breathtaking finished model photographs.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Geometry1 ◈ Modular Origami Basics

Perhaps most origami enthusiasts already know that the word origami is based on two Japanese words: oru (to fold) and kami (paper). Although this ancient art of paper folding started in Japan and China, origami is now a household word around the world. Most people have probably folded at least a paper boat or airplane in their childhood. Origami has now come a long way from traditional models and modular origami, origami sculptures, and tessellations are some of the newer forms.

The origin of modular origami is a little hazy due to the lack of proper documentation. It is generally believed to have taken off in the early 1970s with the Sonobe units made by Mitsunobu Sonobe, although it may have existed earlier. Six Sonobe units could be assembled into a cube. Three of those units could be assembled into a Toshie Takahama Jewel [Tak74] with one additional crease made to the units. With the additional crease direction reversed, Steve Krimball first formed the 30-unit ball [Gra76]. This dodecahedral-icosahedral formation, in my opinion, is the most valuable contribution to polyhedral modular origami. It gave birth to the idea that an unlimited number of origami models could be constructed based on various underlying polyhedra. Later on, Kunihiko Kasahara, Tomoko Fuse, Miyuki Kawamura, Lewis Simon, Bennet Arnstein, Rona Gurkewitz, David Mitchell, Francis Ow, and many others made significant contributions to modular origami. Thomas Hull and Robert Lang added the notable family of the highly mathematical polypolyhedra (a term coined by Lang) that are essentially interwoven polygonal or polyhedral frames [Hul02]. As Lang notes, these polypolyhedra have an “uncanny” beauty [Lan] and personally, I find them extremely challenging and enjoyable to make.

Modular origami, as the name suggests, involves assembling several usually identical modules or units to form one finished model. Modular origami almost always implies polyhedral or geometric modular origami, although there are a number of other modular models that have nothing to do with polyhedra. Dinosaur skeletons made of several square pieces of paper and a traditional Chinese modular unit with which one can virtually construct any form are but a few examples. Generally speaking, glue is not required, but for some models it is recommended for increased longevity, and for some others glue might be essential simply to hold the units together. The models presented in this book do not require any glue except for when they are intended to be rough handled.

The symmetry of modular origami models is appealing to almost everyone, especially to those who have an appreciation for polyhedra. While an understanding of mathematics is useful for designing these models, it is not crucial for merely following polyhedra charts and instructions to construct the models. The beauty lies in the fact that even though mathematics is not one’s forte, one can still construct these models and perhaps even have a different appreciation of the mathematical principles involved. Like any multi-stepped task that requires patience and diligence, the end result of one’s hard work is a reward well earned and enjoyed. Aesthetics and mathematics brilliantly come together in these wonderful origami structures.

Modular origami can be fit relatively easily into one’s busy schedule. Unlike other art forms, one does not need a long uninterrupted stretch of time all at once. Upon mastering a unit that takes very little time, batches of it can be folded anywhere anytime, including the very short free periods that one might have in between other work. When the units are all folded, the assembly can also be done slowly over time. I have been a working mother with two young boys and I am quite aware of how limited free time can be. But as I have found out, modular origami can easily trickle into the nooks and crannies of one’s packed day without jeopardizing much else. Those long waits at the doctor’s office or anywhere else and those long rides or flights do not have to be boring and unproductive any longer. Just remember to carry some paper and diagrams along and you are ready with practically no extra baggage.

Folding Tips and Tools

◈ Use paper of the same thickness and texture for all units that make up a model. This ensures that the finished model will hold evenly and look symmetric. Virtually any paper from color printer paper to gift wrap works. The origami paper commonly available on the market that is colored on one side and white on the other, usually referred to as kami, works for most models. There is a host of other fancy papers available: foil-backed paper, duo, washi, chiyogami, elephant hyde paper, etc.

◈ Pay attention to the grain of the paper. Make sure that when starting to fold, the grain of the paper is oriented the same way for all units. This is important so as to ensure uniformity and homogeneity of the model. To determine the grain of the paper, gently bend paper both horizontally and vertically. The grain of the paper is said to lie along the direction that offers less resistance during bending.

◈ Accuracy is particularly crucial to modular origami, so your folds need to be as accurate as possible. Only then will the finished models look symmetric and neat.

◈ It is advisable to fold a trial unit before folding the real units. This gives you an idea of the finished unit size. In some models the finished unit is much smaller than the starting paper size, while in others this is not so. Making a trial unit will give you an idea of what the size of the finished units—and hence a finished model—might be, starting with a certain paper size. It will also give you an idea about the paper properties and whether the paper type selected is suitable for the model.

◈ After you have determined your paper size and type, procure ALL the paper you need for the model before starting. If you do not have all the paper at the beginning, you may find, as has been my experience, that you are not able to find more paper of the same kind to finish your model.

◈ If a step looks difficult, looking ahead to the next step often helps immensely. This is because the execution of a current step results in what is diagrammed in the next step.

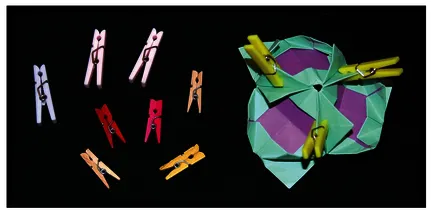

◈ Assembly aids such as miniature clothespins or paper clips are oft en advisable, especially for beginners. Some assemblies simply need them whether you are a beginner or not. These pins or clips may be removed as the assembly progresses or upon completion of the model.

◈ During assembly, putting together the last few units, especially the very last one, can be challenging. During those times, remember that it is paper you are working with and not metal! Paper is flexible and can be bent or flexed for ease of assembly.

◈ After completion, hold the model in both hands and compress gently to make sure that all the tabs are securely and completely into their corresponding pockets. Finish by working around the ball.

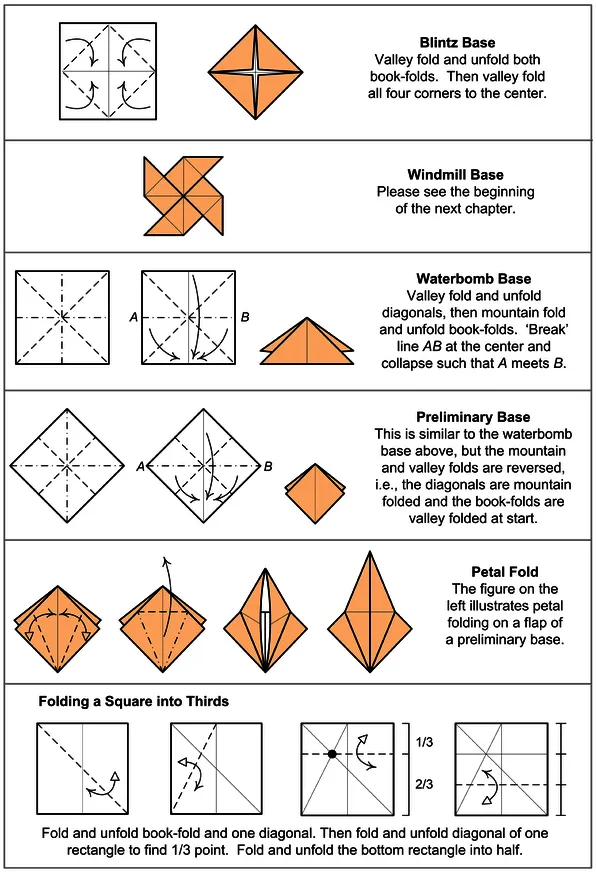

◈ Many units involve folding into thirds. The best way to do this is to make a template using the same size paper as the units. Fold the template into thirds using the method explained in the Origami Symbols and Bases section of this chapter. Then use the template to crease your units. This saves time and reduces unwanted creases.

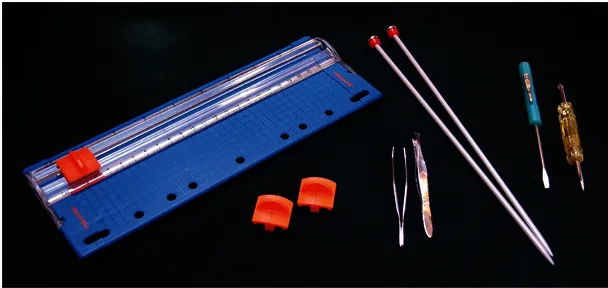

◈ Procure the minimal basic handy tools listed on the next page. These tools assist in sizing paper, making neat crisp creases, curling paper (used extensively in this book), and assembling models.

Left to right: Portable photo trimmer with replaceable blades are great for trimming origami paper to size. Tweezers are useful for accessing hard-to-reach places. Knitting needles, screwdrivers, or similar objects, such as narrow pencils work well for curling paper (used extensively in this book).

Miniature clothespins may be used during model assembly as temporary aids to hold two adjacent units together. The clothespins may be removed as the assembly progresses or after completion.

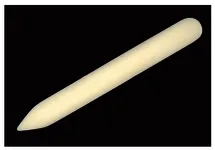

A traditional bone folder (left) is used for making neat and crisp folds. Plastic milk jug handle cutouts, often found at grocers’ refrigerator (with some luck) or objects such as discarded credit cards work almost as well.

Origami Symbols and Bases

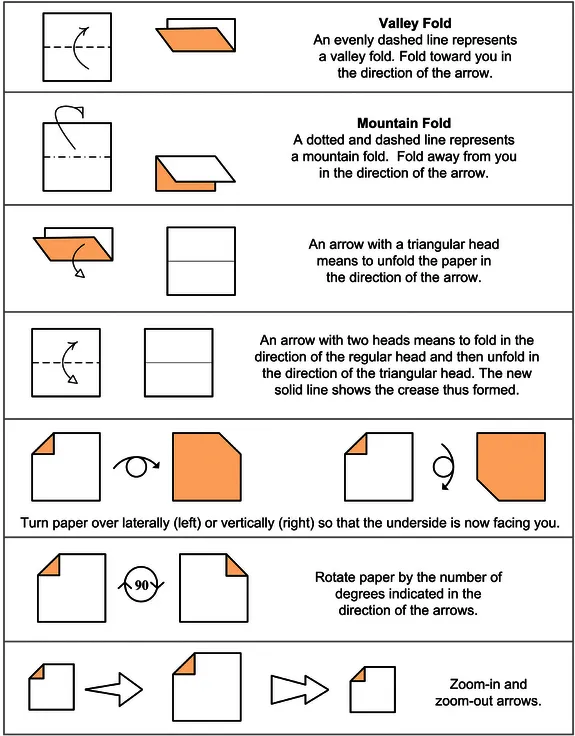

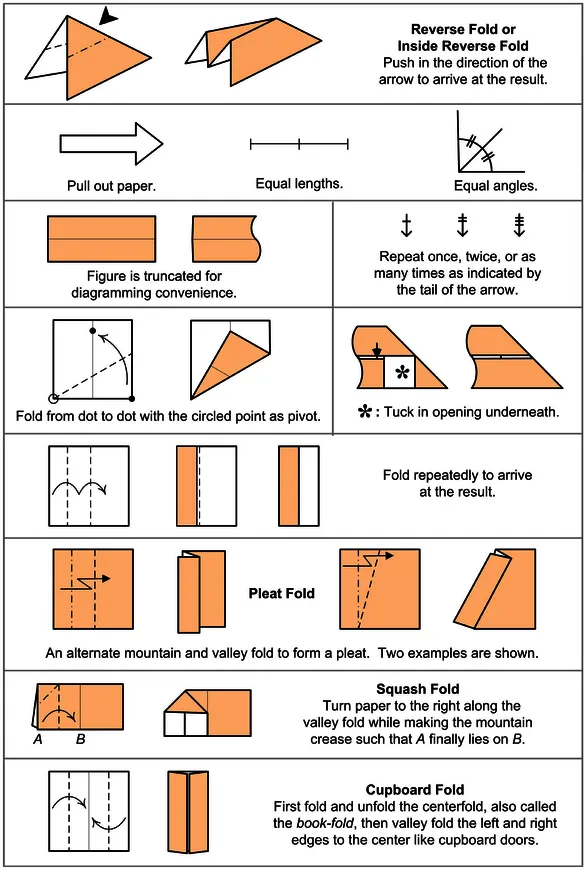

This is a list of commonly used origami symbols and bases. While it covers all symbols and bases referenced in this book, it is by no means a complete list.

Modular Origami and Mathematics

“Mathematicians often rhapsodize about the austere elegance of a well-wrought proof. But math also has a simpler sort of beauty that is perhaps easier to appreciate: It can be used to create objects that are just plain pretty—and fascinating to boot.” This statement by Julie J. Rehmeyer [Reh08] echoes my own sentiments. In my opinion, polyhedral modular origami is an inspiring example of how mathematics, art, and beauty all come together in a wonderful cross-pollination of disciplines that all can understand and appreciate without the rigors of a proof. It perfectly demonstrates the balance and symmetry often found in mathematics in a hands-on intuitively gripping way and can be compelling to mathematicians and artists alike. A mathematician’s delight in pondering the symmetry of the polyhedra underlying the models is just a different spin on the same delight an artist experiences when contemplating the beauty of the exact same object. Human beings instinctively find symmetry pleasurable and beautiful—studies have even linked symmetry to our perception of beauty in facial features, though it is not quite relevant here, it is worth mentioning.

Although most people view origami as child’s play and libraries and bookstores tend to shelve origami books in the juvenile section, there is much more to origami than generally perceived. There is such a primal connection between mathematics and origami that a separate international origami conference, Origami Science, Math, and Education (OSME) was spun off in 1989. Professor Kazuo Haga of the University of Tsukuba, Japan, appropriately proposed the term Origamics at 3OSME in 1994 [Hul02] to refer to this genre of origami that is heavily related to science and mathematics. The mathematics of origami has been extensively studied not only by origami enthusiasts but also by many mathematicians, scientists, and engineers as well as artists. These interests date back to at least the late nineteenth century when Tandalam Sundara Row of India wrote the book Geometric Exercises in Paper Folding in 1893 [Row66]. He used novel methods to teach concepts in Euclidean geometry by simply using scraps of paper and a penknife. The geometric results were so easily attainable that it inspired quite a few other mathematicians to investigate the geometry of paper folding for the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 #x25C8; Modular Origami Basics

- 2 #x25C8; Windmill Base Models (Created October 2006)

- 3 #x25C8; Blintz Base Bouquets (Created May 2004)

- 4 #x25C8; Decorative Icosahedra (Created 2006-2008)

- 5 #x25C8; Embellished Sonobes (Created 2006-2007)

- 6 #x25C8; Embellished Floral Balls (Created 2006-2008)

- 7 #x25C8; Planars (Created 2002-2003)

- Afterword

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ornamental Origami by Meenakshi Mukerji in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Geometry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.