As teachers, we know children don’t develop in isolation. Rather, all domains of their development are impacted by their environments and the systems making up those environments. The most well-known framework of this concept is Bronfenbrenner’s (1979; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) bioecological systems model. Generally, teachers are presented with examples of systems models placing students at the center of the conceptual model to call our attention to the myriad factors impacting learning development. In this chapter, the focus is on teachers and the multiple systems impacting our professional and personal development. When we take the time to understand and reflect on these factors, we can better manage the expectations and impact created by each system level. This allows us to plan strategies and to meet systems expectations in ways that aren’t as disruptive to best teaching practices. Teachers can develop coping mechanisms and structures within themselves and their microsystems to buffer against potential negative impacts from the stress created by systems outside our own control.

Understanding the Bioecological Systems Model

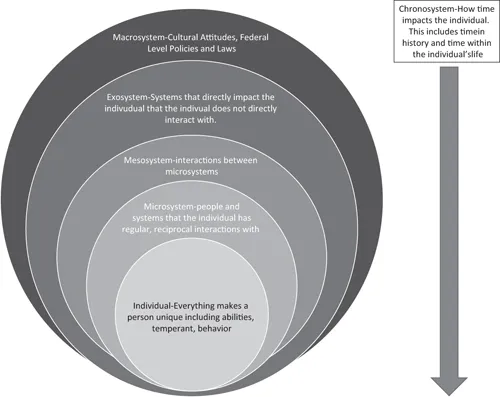

The bioecological systems model is usually drawn as a series of concentric circles with an individual in the center circle. Each larger circle represents a system impacting the development and well-being of the individual at the center. The farther the circle from the individual, the less control and reciprocity exist in the relationship between systems at that level and the person in the center. Closest to the individual is the microsystem, then the mesosystem, the exosystem, and finally the macrosystem. The chronosystem, which represents time, is the final level in the bioecological systems model. The chronosystem is not represented as one of the concentric circles, but rather as an overlay impacting systems at all levels.

In the center of our model is you, the teacher. This chapter presents a generalized model with systems many teachers encounter. As you read, it’s important for you to reflect on what your personalized bioecological model looks like. Each teacher’s experience varies and even the systems we have in common may impact individual teachers differently. For example, almost all teachers interact with special educators. Depending on the microsystem-level relationship you have with the special educator, the meso-level relationships of the people in the microsystem and how they interact with the special educator, and the exo- and macrosystem factors impacting special education provision at your school, this relationship may be quite positive and supportive for you. Perhaps, if you are working in a well-funded district with an adequate number of special education teachers to meet student need, and you are paired with a special educator who shares your values and ideas about best practice in education and who has strong, positive relationships with students and their families, you will feel supported and your personal and professional development will be positively impacted. Conversely, if your school district has more students with special educational needs than it has special educators to provide assigned IEP minutes, and you are paired with a special educator who is burned out and negatively views students and families, the two of you may fundamentally disagree about how to meet the needs of the children in your classroom. When this happens, your personal and professional development can be negatively impacted.

At the center of our bioecological systems model is the individual. Everyone is made of a personal biological, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral characteristic set. These characteristics both influence and are products of development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). For example, Ms. Awashthi, with an easy-going temperament, will likely experience more pleasant interactions with the occupational therapist assigned to provide special education minutes for several children with autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in her classroom. As a result, Ms. Awashthi will be more likely to learn about and try new approaches to learning and classroom management. Through repeated, positive interactions with the occupational therapist working with students in her classroom, Ms. Awashthi will master the use of more effective teaching strategies with her students. The more effective teaching and management strategies build a foundation for increased feelings of self-efficacy and more positive interactions with students in the teacher’s microsystem. Conversely, Mr. Milligan is slow to warm and struggles with depression. He may have difficulty building a working partnership with the same occupational therapist. The symptoms of Mr. Milligan’s depression could impact his ability to find the energy and motivation to try new strategies offered by the occupational therapist. As a result, Mr. Milligan’s interactions in his microsystem, both with the occupational therapist and his students, are more likely to be negative because he did not develop the knowledge and skills to meet their behavioral and educational needs. Consequently, Mr. Milligan’s negative interactions with the occupational therapist and the classroom management challenges occurring in his microsystem can cause more stress and negative emotional reactions. These factors will exacerbate Mr. Milligan’s existing mental health challenges, continuing to impact negatively his relationships with others in his microsystem.

Directly outside of the individual is the microsystem. The microsystem is made up of teachers’ interactions with others and personal relationships. This system includes personal relationships with romantic partners, the teacher’s own children and their caregivers, siblings and parents, and anyone else the teacher interacts with regularly in their personal life. Professional relationships are also situated in the microsystem. These relationships with our principals, school support staff, coworkers, teacher coaches, special education staff and our students and their caregivers are part of our microsystems. Most teachers have quite large microsystems. Microsystems also change frequently. After all, every autumn, teachers’ microsystems grow by at least 20 children and their caregivers. This leaves teachers with many interpersonal relationships impacting their personal and professional development. According to Bronfenbrenner (1979), when one member of your microsystem undergoes a developmental change, you’ll experience a change as well. For example, if your teaching assistant goes to a conference and learns new methods of supporting positive classroom behaviors without yelling, his development as a more competent classroom manager will help you as the classroom teacher to grow as well. Perhaps the assistant teacher will share those strategies with you and you’ll improve your management skills as a team. Or maybe your assistant’s increased competency in managing classroom behavior frees you to spend less time managing behavior and more time planning for project-based learning.

Many of the people in your microsystem have relationships with each other. These relationships make up the next system in the bioecological systems model, the mesosystem. The mesosystem is “a system of microsystems” (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 25). This system represents how your microsystems interact with each other. The outputs of each of these relationships in the mesosystem impact the individual at the center of the model by mitigating or exacerbating existing stressors or by creating them. For teachers, this can mean how students interact with each other, how the teaching assistant in your classroom and your student teacher interact, and the nature of the relationships your school administrator has with your students’ parents. In your personal life, the relationship your children have with your romantic partner exists in your mesosystem. A major part of your mesosystem is the interrelationship between your work setting and home. A common mesosystem-level challenge I and many other educators face is the difference between my school calendar and my daughter’s school calendar. When the vacation days on our calendars don’t align, the discrepancy creates stress for me as I have to find quality childcare and miss the extra time with my daughter. When teachers’ calendars do align with their own children’s schools, stress may arise because a teacher isn’t able to drop her children off for the first day of school because it is also her own first day of school.

Beyond the mesosystem sits the exosystem. Entities in the exosystem impact the person at the center without any direct interactions with that person. The teachers’ union at your school is situated in the exosystem, as are the superintendent of your district and the school board. These groups negotiate your salary and benefits and have the power to dictate the curriculum, both of which impact your day-to-day life, but as a teacher at the center of the model, you don’t interact directly with them. Other examples of exosystem-level units impacting teachers are state-level education policies and funding streams, state boards of education and teacher licensing requirements and exams, university teacher preparation curricula, packaged curricula, including The Creative Curriculum® (Teaching Strategies, 2016), and textbook and educational testing companies such as Pearson and Routledge. Each of these systems impacts teachers although teachers rarely interact directly with the systems other than to submit paperwork, take exams, or implement their curriculum. The media is also in the exosystem. Movies like Dangerous Minds, memes of exhausted teachers throwing papers, and news coverage of the local teachers’ strike contribute to a larger, societal value of teachers and our identities as educators.

The cultural views we hold about teachers are in the macrosystem, represented by the last and largest of the concentric circles. This system encompasses all the other systems and includes the cultural ideologies upon which the other systems are built. Within the macrosystem lie societal beliefs about the goals of education, what kinds of skills our students should learn in schools, and what level of prestige is given to teachers. American attitudes about inclusion and special education and culturally and linguistically diverse learners are positioned in the macrolevel system level. The Common Core State Standards emerged as a result of macro-level systems. Together with the Council of Chief State School Officers, the National Governors’ Association pushed for unified standards for college and career readiness (Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2018). If you are a teacher in one of the 41 states that adopted Common Core, this macro-level initiative impacts the curriculum chosen in your exosystem, which then in turn impacts the instructional interactions you have in your microsystem.

The final component of the bioecological systems model is the chronosystem. It accounts for the ways that cultural ideologies and bodies of knowledge shift over time. Bronfenbrenner added the chronosystem to acknowledge the impact that these shifts have on systems at every level and thus on individual development. A chronosystem-level factor significantly impacting early childhood teachers is the scientific research completed in the last 30 years, establishing a foundation for understanding how young children best learn and develop, and of course how all the systems around the children impact their development (Allen & Kelly, 2015). One significant example emerging in recent years is the understanding of the prevalence and impact of trauma on overall health in the United States. Beginning in 1998 (Felitti et al.), researchers began to connect childhood trauma to changes in the brain and body impacting development and health over lifetimes. Initial data from this CDC-Kaiser Permanente study found about two-thirds of people, regardless of education or socioeconomic status, experienced at least one adverse childhood experience. Understanding of the prevalence and impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) continues to expand our perception of what constitutes ACES (Institute for Safe Families, 2013) and how ACES impact individual health and development throughout a person’s life (Anda et al., 2006).

Another component of the chronosystem is the stage in the individual’s career. This accounts for the variance in the impact of each system depending on the person’s age and life-cycle events. For example, if you are a new grad entering your first year of teaching, your chronosystem demonstrates that the impact each system has on your professional development is different from what would be the case for a veteran teacher two years from retirement.

This chapter provides an example bioecological systems model for a Chicago Public Schools Head Start teacher. It will be helpful for you to review this example and create a draft of your own bioecological systems model before continuing to the next section of this chapter (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Adapted from Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979) The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press and Bronfenbrenner, U. & Morris, ...