Introduction

Europe is currently undergoing large-scale demographic and cultural change. An otherwise ageing and secularizing corner of the world has received an influx of younger, non-Western and often religious migrants. This influx has been increasingly and consistently contested by a resurgent far right from the 1980s onwards (Klandermans & Mayer, 2006, p. 3). For decades, as the conflict revolved around race, ethnicity and nationality – Africans and Arabs, Turks, Moroccans, and Pakistanis – some on the far-right upheld Islam as a positive, conservative force.

That has changed. In tandem with a long list of spectacular acts of political violence committed in the name of Islam and controversies such as the Muhammed cartoon crisis1, Muslims and Islam have now become the predominant enemy for the far right in Europe and beyond.

This book is about that anti-Islamic turn and expansion of the far right. It is about a growing movement and subculture that is transnational in scope ranging from the United States, Western Europe, and, increasingly, Central and Eastern Europe. It has old ideological roots, but the movement began to coalesce online in the wake of the terror attacks on the United States by Al-Qaeda on 11 September 2001 (9/11). Since then, the anti-Islamic struggle has given rise to several distinct waves of activism under the names of Stop Islamization, Defense League, Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the West (Patriotische Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes, PEGIDA) and others. Anti-Islamic and anti-Muslim groups flourish online. In party politics, new initiatives such as the Dutch Pim Fortuyn List (Lijst Pim Fortuyn, LPF) and later Geert Wilders’ Freedom Party (Partij voor de Vrijheid, PVV) made opposition to Islam their main issue.

The parties that mobilize on anti-Muslim and anti-Islamic ideas and arguments are now the most studied of all the party families (Mudde, 2016). In contrast, we know less about the broader movement and subculture.2 An important reason for precisely why far-right parties are the subject of so much research, and why the anti-Islamic movement(s) and subculture merit closer scrutiny, is the idea that these initiatives either want to destroy democratic society itself or will in some way lead to its corrosion.

Franz Timmermans, the first Vice President of the European Commission, stated in an official speech that “The rise of islamophobia is one of the biggest challenges in Europe. It is a challenge to our vital values, to the core of who we are” (2015). Given this notion of a threat to “our” values, it is striking that the anti-Islamic far right in Western Europe and North America argue that they are defending democracy and freedom of speech (Betz & Meret, 2009, p. 313), while often proclaiming their support for Jews, gender equality, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transsexual (LGBT) rights (e.g. Dauber, 2017, p. 52).3 If we turn the clock back two decades, we find a surge in neo-Nazi violence (Koopmans, 1996) and outspoken hostility towards Jews, homosexuals, and modern gender norms was commonplace.

Hearing far-right politicians and activists talk in such different terms today may appear paradoxical, given the legacy of opposition towards both progressive and liberal ideals, movements, and parties. Is the far right, which has been so closely tied to antagonism towards these very groups, now one of their defenders?

Viewed through the lens of history, it is their apparent self-portrayal as defenders of progressive and liberal ideals – and not their opposition to Islam and Muslims – that is most distinctive. In academic circles, this is often portrayed as being only skin deep, a thin veneer masking their true positions – and that the far right hides a radical “back stage” behind its moderate “front stage” (Fleck & Müller, 1998, p. 438) which is racist, anti-Semitic, homophobic, against women’s rights, and hostile to democracy.

It is defined as a transparently strategic vocabulary (Scrinzi, 2017) used to circumvent and defend against allegations of racism. This is deemed a necessity on their part, since openly racist remarks have been stigmatized and pathologized (Lentin & Titley, 2011, p. 20) ever since the total defeat of the Axis powers in World War II (Jackson & Feldman, 2014, p. 7). The claims by Marine Le Pen of the French Front National (FN) to defend women’s rights are, for instance, understood as “instrumental” and “pseudo-feminist” (Larzillière & Sal, 2011). In much the same way, Mayer, Ajanovic, and Sauer (2014) state that the far right exploits gender and LGBT arguments strategically in order to denigrate Muslim men. Others have conceptualized this as homonationalism (Puar, 2013; Zanghellini, 2012),4 and femonationalism (Farris, 2012, 2017).5

Critical positions and scepticism are not without merit. For instance, studies of the British National Party (BNP) that go beyond the “front stage” by examining speeches and memos not intended for the public reveal that they toned down their anti-Semitism and anti-democratic positions as a ploy to win over new recruits and circumvent opposition from mainstream society (Jackson & Feldman, 2014, p. 10). These findings are in line with the broad consensus in the literature. Yet, we risk misconstruing the anti-Islamic turn and expansion if we limit ourselves to a theoretically based rejection or if we rely exclusively on single-case evidence from organizations with a clear fascist legacy. As a starting point for mapping the anti-Islamic movement and to investigate this apparent paradox and its ramifications on a broader scale, I pose the two following research questions:

- RQ1 What characterizes the anti-Islamic movements’ structure and composition?

- RQ2 How, and to what extent, does the anti-Islamic movement incorporate progressive and liberal values?

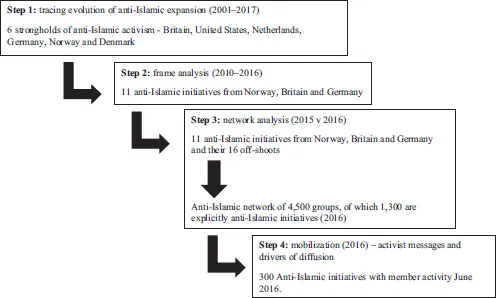

In order to investigate the movements’ configuration and degree of entanglement with progressive and liberal ideals, this book provides a study of four specific dimensions: 1) the background of leaders; 2) their official ideology; 3) organizational networks; and 4) the mobilization of sympathizers. The extent to which liberal and progressive positions and arguments permeate the anti-Islamic movement has far-reaching consequences for our basic understanding of what the anti-Islamic movement is. In addition to saying something about their entanglement with progressive and liberal ideals, these dimensions give us insight about the anti-Islamic turn on the far right.

First, tracing the waves of activism and the biographies of the leaders, representatives, and ideologues provides us with insight into their motivation for joining the anti-Islamic cause and whether they have their roots in the old far right or not. Second, studying their official ideology (front stage) gives an indication of whether their positions are consistent or fragmented across countries and organizations. Third, network analysis tells us whether these initiatives form a cohesive whole or consist of disjointed communities. Taken together, the historical and biographical overview, alongside the analyses of ideology and networks, go to the core of the matter. Is this really a movement, or is it just a question of different groups driven by national, regional, and local legacies and peculiarities? And do they represent a continuation of the old far right or not? By studying their mobilization, we uncover whether they have managed to recruit moderates or extremists, and to what extent they are aligned with the official ideological platform espoused by the leaders. It also provides insight into the drivers of their continued online mobilization and ability to spread their message, and why certain messages get more traction than others.

The four steps

The broader anti-Islamic turn consists of two parallel developments: first, an anti-Islamic reorientation of pre-existing radical right parties; second, an anti-Islamic expansion of the far right with new political initiatives. While the expansion includes some electorally successful parties, such as Pim Fortuyn’s LPF and Geert Wilders’ PVV, both in the Netherlands, it largely consists of alternative news sites and blogs, think-tanks, street protest groups such as the English Defence League (EDL) and PEGIDA, and minor political parties. Empirically speaking, the universe of cases dealt with in this book is limited to the anti-Islamic expansion. The findings and theoretical claims, however, have some bearing on the broader anti-Islamic turn.

The book starts by tracing the growth of anti-Islamic activism between 2001 and 2017, focussing on initiatives and central figures from six “stronghold” countries: Britain, the United States, the Netherlands, Germany, Norway, and Denmark. This is followed by a frame analysis of official statements by 11 key initiatives known for their anti-Muslim and anti-Islamic rhetoric in Germany, Norway, and Britain. All three countries are epicentres of anti-Islamic activism. Norway was the first country to have an explicitly anti-Islamic activist organization in Stop Islamization of Norway (SIAN) in 2000. Britain was the location where the online communities first gathered for a street march in 2005, and which witnessed the rise of the EDL in 2009. Finally, Germany gave birth to the latest version of anti-Islamic activism with PEGIDA in 2014, which has since spread across Europe (Berntzen & Weisskircher, 2016). I then trace the online anti-Islamic network starting with these 11 anti-Islamic initiatives’ from Norway, Britain and Germany and 16 of their offshoots across the world in March 2015 and March 2016; that is, before and after the “refugee crisis”. When examining members of these networks, the case selection consists of the anti-Islamic groups found in the network analysis that were active during the summer of 2016 – totalling 300 groups across Europe, North America, and Australia (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1The four steps taken to explore the anti-Islamic movement and expansion

Findings and the argument(s)

As the old, highly authoritarian and ethnocentric far right lost its vitality, a new phenomenon arose to take its place: anti-Islam. It is a new addition to the far-right family, but no child of the old far right. The anti-Islamic cause was borne by a curious mix of people with leftist and conservative backgrounds, all of whom professed their attachment to many liberal ideals. Their leaders and intellectuals – many of them journalists and historians – came to see their own political camps as ignorant of the dangers posed by Islam. In their eyes, Islam was not a regular religion but a totalitarian ideology equivalent to communism and fascism. Propelled by their belief in a civilizational struggle between the West and Islam, these activists managed to establish a transnational anti-Islamic movement consisting of activist groups, think-tanks, and alternative media outlets, as well as some political parties. The movement itself has undergone four waves of expansion in response to acts of terror and other moral shocks, starting with 9/11. Most of their claims and positions about what they represent resonate with broad majorities in Western Europe: free speech, preservation of the Christian heritage, democracy, gender equality, LGBT rights and the protection of Jews. Their outspoken hostility to Islam and Muslims further resonates with substantial minorities.

Their civilizational worldview, which combines previously divergent political projects, is broadly consistent across organizations and countries. They continuously include both traditional and modern perspectives on a broad range of issues. On the one hand, hostility towards the Muslim minority and defence of traditions sits well with the older far right. On the other hand, their inclusion of modern gender norms and key liberal positions are clearly at odds with the traditional far right with its rigid views on gender roles and hostility toward democracy. For instance, when it comes to the supposed threat posed by Islam and Muslims to women’s rights, they vacillate between “protector frames” with a male point of view (our women), and “equality frames” with a female point of view. I define this ideological duality as strategic frame ambiguity.

The anti-Islamic network mirrors this ideological duality. Anti-Islamic groups reach out to animal rights, LGBT, and women’s rights groups, as well as Christian conservatives and Jewish and pro-Israeli initiatives. Some, but not all, of these reciprocate. Furthermore, both main components of the ideology – 1) Islam as an existential threat enabled by “the elites” either through a willed conspiracy or due to their sheer ignorance; 2) which undermines Western traditions and Christianity, democracy, gender equality, and minority rights – resonate with the online activists and followers. In terms of the two overarching research questions, the findings in this book can be summarized in one structural and one ideology-centric argument:

- First, the initiatives that make up the anti-Islamic expansion of the far right comprise a transnational movement and subculture with a consistent worldview and prominent ideologues.

- Second, the anti-Islamic movement and subculture is characterized by a semi-liberal equilibrium.

It is to the second argument I now turn. The transnational anti-Islamic movement exists in a state of balance between modern and liberal values on the one hand, and traditional and authoritarian values on the other. Both components are part of their civilizational, anti-Islamic identity. I have chosen to describe this state of balance as semi-liberal. Therefore, it is also semi-authoritarian. Using the label of liberal instead of authoritarian is justified by the fact that their leftist-to-conservative-liberal stances largely predate clearly authoritarian ones. When looking at the far right in its totality, the anti-Islamic movement represents a profound unmooring from ethnically based nationalism and pervasive authoritarianism, as well as homophobia and anti-Semitism. This sets them apart from the older far right, which is firmly rooted in precisely these values.

Although the old far right with its all-pervasive authoritarianism and ethnocentrism certainly exists in a diminished state today, most pre-existing radical right parties in Western Europe have undergone an ideological transformation that makes them ideologically similar to the anti-Islamic movement that arose after 9/11. Herbert Kitschelt (2012) described this transformation as a partial decoupling between authoritarianism and the radical right through an adoption of liberal positions on many issues. The starting point was an authoritarian one.

For the anti-Islamic movement that emerged after 9/11, the precise opposite holds. As the anti-Islamic movements’ roots and original set of ideas come from outside the far right, it represents a partial coupling between liberalism and authoritarianism from a liberal starting point.6 In other words, the anti-Islamic expansion is in fact liberalism that has drifted to the far right. What is the cause of this drift? My material clearly points to the pivotal role of their conception of Islam and Muslims as the ultimate embodiment of authoritarianism, narrow-mindedness, patriarchy and misogyny as the root cause. Ostensibly starting from a position of tolerance, they have ...