eBook - ePub

Defrosting Ancient Microbes

Emerging Genomes in a Warmer World

This is a test

- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Ice is melting around the world and glaciers are disappearing. Water, which has been solid for thousands and even millions of years, is being released into streams, rivers, lakes and oceans. Embedded in this new fluid water, and now being released, are ancient microbes whose effects on today's organisms and ecosystems is unknown and unpredictable. These long sleeping microbes are becoming physiologically active and may accelerate global climate change. This book explores the emergence of these microbes. The implications for terrestrial life and the life that might exist elsewhere in the universe are explored.

Key Selling Points:

- Explores the role of long frozen ancient microbes will have when released due to global warming

- Describes how ice preserves microbes and microbial genomes for thousands or millions of years

- Reviews work done on permafrost microbiology

- Identifies potential health hazards and environmental risks

- Examines implications for the search for extraterrestrial life.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Defrosting Ancient Microbes by Scott Rogers,John D. Castello in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Cell Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Reaching Backwards

“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards”

Søren Kierkegaard

Reviving the “Dead”

Can the dead be revived? In Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Lost World,” a professor discovers an ancient world suspended in time. Life is as it was millions of years ago. It is a world in which “the ordinary laws of nature are suspended. The various checks which influence the struggle for existence in the world at large are all neutralized.” This was science fiction when it was published in 1912. But it is not so far-fetched. What if there were a way to reach back in time and drag ancient life into the present? Actually, it has been occurring naturally on Earth for millions, if not billions of years. Scientists have recently done the same.

Prehistoric organisms are living and growing today. We can revive them, or they can spontaneously revive by melting out of their icy tombs. They are probably on your skin and in your hair at this very moment. Some are shades of russet, bronze, and mahogany. Others have soft, mist-like filaments reaching into the air. Some look like microscopic space ships. There are those that appear like an opaque slime with a gelatinous glow. And others are so very tiny that, in one quick breath, hundreds can effortlessly be drawn into your lungs and into your blood. Quite a long and marvelous journey for a prehistoric spoor.

You might think this is unbelievable, but there are special places on Earth where ancient life is preserved. While this may generate visions of crystallized amber or the tombs of Egypt, there is a much more common and effective preservation method for sustaining life, common on Earth, and utilized every day by you and everyone you know. It is ice. Humans have used ice for centuries to preserve foods, but it has been a natural preservative of life for millions of years. Much evidence has accumulated over the past 200 years, primarily in the past 30 years, indicating that many microbes, as well as some multicellular organisms, can be frozen and then revived when the ice melts decades, centuries, or millennia later. Yearly, millions of tons of organisms are entrapped in ice, and currently many more are melting out of the ice due to global climate change, and the warming that it has caused.

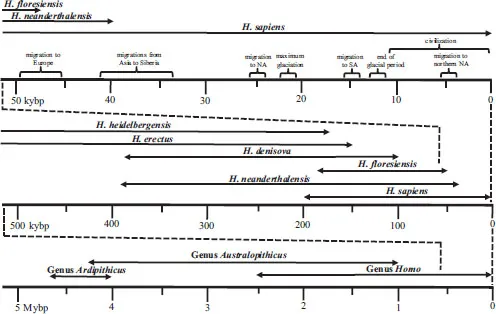

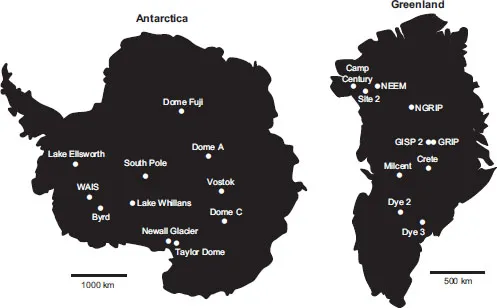

In the polar regions, much of the ice remains frozen, sometimes for millions of years. It continually builds up millennium after millennium, eventually melting or subliming, thus releasing its cargo of viable microorganisms. Ice has formed for so long that excavating deep within its recesses one can construct a timeline long into the past. Just as sedimentary rock layers have been laid down and preserve different sequential points of time, so too are layers of ice laid down over time to preserve a sequential record of past times. In layer after layer, the pages of history can be retraced, back to 1930, 1800, 1200, 500; and to 1000 ybp (years before present), 5000 ybp, 100,000 ybp, 400,000 ybp, 2 million ybp, and beyond; including times beyond human existence (Fig. 1.1). Times of global warming, cooling, volcanic eruptions, disease epidemics, pandemics, and other events can be investigated in these moments frozen in time within ice. Some of the ice buried deep beneath the surface of the Earth is so old that it is difficult to imagine that time and place. It is certainly out of our day-to-day experience. There are glaciers and ice domes that are miles deep in Greenland and Antarctica from which ice cores have been extracted (Fig. 1.2). Other slices through time exist on the surface, having been pushed up and out by the tremendous forces of the glaciers. Sections of this ice provide rich images of the distant past. But this is much more than an academic curiosity. Prehistoric life can actually be incorporated into our modern world. A virus coughed up from a Neanderthal’s lungs might emerge today, having been in suspended animation for 50,000 years. An influenza or smallpox virus strain that has been frozen for decades, centuries, or millennia may melt from a glacier today to infect a population of humans never exposed to these specific virus strains. Thus, there would likely be no remnant immunity in this population. These immunologically naive populations would be extremely vulnerable to these completely unknown pathogenic viral strains.

Figure 1.1 Timelines of the past 5 million years. This spans the ages of ice cores from Earth currently available for scientific study, as well as the span of several species in the genus Homo. At the top is a scale representing the past 50,000 years, indicating the species of Homo present, the major human migrations (often coinciding with global climate changes), the last major ice age, and the extent of human civilization (approx. 11,000 years). The middle timeline shows the extent of members of the genus Homo during the past 500,000 years. Homo sapiens have existed for approximately the last 200,000 years. The lower timeline shows the spans for three genera of human-like species, including Ardipithicus, Australopithicus, and Homo.

Figure 1.2 Maps of Antarctica and Greenland, showing the locations of some of the major ice cores that have been analyzed by scientists. The cores from Greenland (GISP 2, Greenland Ice Sheet Project; and others) and Antarctica (Vostok, Dome C, and others), have yielded information on CO2 and methane levels, as well as on temperature and microorganisms, reaching back as far as 800,000 ybp.

Glaciers and polar ice caps are constantly forming and melting. Global warming events accelerate the rate of release of these frozen organisms. During ice ages more of the organisms are entrapped in glaciers. Most of the terrestrial freshwater ice on Earth is in Antarctica (over 91%) and in the Arctic (about 8%), and this is approximately 70% of all of the freshwater on Earth. But there also are glaciers in the Alps, the Southern Alps, the Rockies, the Andes, the Himalayas, and many other locales, including on Mt. Kirinyaga (formerly Mt. Kenya) and Mt. Kilimanjaro near the equator in Africa (although the ice on these two mountains has almost completely disappeared during the past two decades). The water from these glaciers ends up in streams, lakes, and oceans. Many people drink the water and eat the plants and animals that use these sources of water, not realizing that they may be ingesting organisms that are thousands of years old, or older. Microbes are transported to the glaciers by wind, rain, snow, fog, or by macroorganisms. Some of the transport is over very long distances. For example, biological specimens originating from close to the equator have been found in Arctic and Antarctic ice. So, no matter where you go on Earth, you are never far away from a source of these organisms released from ancient ice.

There have been cycles in the Earth’s history when the climate has been warmer and the ice melted. There also were cycles when the Earth was much colder and might have looked like a huge snowball when all of the oceans were covered by thick ice all the way to the equator. The last one of these occurred approximately 600–700 million years ago. Ice has waxed and waned throughout time. Indeed, glaciers constantly form at one end and melt at the other. Sometimes they recede and sometimes they advance. Ice constantly cycles and so do the organisms and unique genomes within them. This organism and genome recycling has broad-ranging implications in terms of evolution, epidemiology, and pathogenicity. Glaciers are rich repositories of entrapped organisms. Upon melting or sublimation (ice turning into water vapor), some of the microbes resume metabolic activity and multiply. Each organism has a unique history, which constantly intermingles, overlaps, and collides with others. Ice ages come and go, as do ancient microbes. History does repeat itself. Mini ice ages have occurred within the past several hundreds of years. Did these affect our ancestors? Do they still affect our lives? They did and they do.

How Ice Affects Life

Although life persists in glacial ice, one of the most inhospitable environments on Earth, why should you care? After all, most of us don’t live in, on, or even in close proximity to ice. Will these organisms affect you, your family, or your neighbor? The quick answer is that they probably can, and they probably already have affected you many times during your life, although you probably did not even comprehend the effects. Research is needed to address the what, when, where, why, and how of life in ice and may provide answers to questions that have perplexed biologists for years; while raising other provocative questions. A few examples follow.

In 1918–1919, the so-called “Spanish” flu (a strain of influenza A virus, which actually originated in China) killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide, many times more than the number of soldiers who died in action in World War I (ongoing at that time); making it the most deadly disease pandemic ever to inflict mankind (at least in recorded history). It killed otherwise healthy young persons, as well as the very young, very old, and the infirm who are the more typical flu victims. Influenza virologists still are not certain why this particular influenza was so deadly although it appeared to have triggered an extreme immune response, causing fluids to build up in the lungs, thus suffocating patients. Some results indicate that genes from two or more different strains recombined to form this deadly strain of influenza. Where did it come from? It disappeared almost as quickly as it appeared, and hasn’t been seen since. It is possible that it still exists and might reappear as another pandemic. There is evidence that this can, and indeed has happened with other similar viruses. For example, in 1977, a strain of “Russian” influenza appeared in northern China. It subsequently spread throughout the entire world. This virus strain was almost identical to an influenza strain that caused an epidemic in 1950. Because the influenza virus is highly changeable, it is unlikely to have maintained itself unchanged for 27 years while actively replicating within a susceptible host. One possible, and tacitly accepted explanation by some virologists, is that it was preserved in a frozen state somewhere. But there also is no direct evidence to support this hypothesis. We are currently searching for influenza (and other) viruses in various types of environmental ice. Other pathogens (viruses, as well as bacteria, fungi, and others) also may be in states of suspended animation in glaciers.

When viable viruses and other pathogens of humans, animals, and plants are released into the streams, lakes, and oceans from melting glaciers, they can then move further, being carried by wind, clouds, or animals. This is well documented. In the early twentieth century, it was discovered that bacteria were ejected into the air from water into which they had been seeded. The concentration of bacteria in the aerosol was far higher than that in the water. Mycobacterium intracellulare, the cause of Battey infection, can become airborne from the sea. Foot and mouth disease virus, which causes a very serious disease of livestock, is concentrated tenfold by foaming. There is a high correlation between the incidence of viral disease and the use of wastewater for spray irrigation of crops in Israel. Viruses in seawater become adsorbed on air bubbles, and are concentrated and ejected into the air upon bubble bursting. Virus-containing droplets are carried considerable distances by the wind. Several years ago, we (JDC) demonstrated that infectious tomato mosaic tobamovirus (ToMV), a common and widespread plant virus, is present in clouds on the summit of a high peak in the Adirondack Mountains of New York and in fog collected off the coast of Maine. Healthy spruce seedlings exposed to the air but not to native soil in the high peaks of the Adirondack Mountains became infected with ToMV, suggesting that the airborne virus is infectious. The origin of ToMV in clouds and fog is unknown, but because the virus is commonly found in water, it is possible that aerosolized virus from fresh or marine waters is a potential virus source. It is equally likely that the virus melted from the glaciers and snow, since we have found these viruses are well preserved in glacial ice.

Caliciviruses are an interesting group of animal pathogens that present yet another interesting pathway for pathogen movement from sea to land. Many of these viruses probably originated in the oceans. Some of these viruses, most notably vesicular exanthema of swine virus (VESV) and San Miguel sealion virus have wide host ranges that include whales, dolphins, walruses, sealions, fur seals, fish, pigs, donkey, mink, fox, muskox, bison, cattle, sheep, and primates including humans. The marine caliciviruses are capable of producing similar disease in a wide variety of hosts including livestock and humans. VESV is the cause of a severe vesicular disease of pigs that first appeared in 1932 on a swine farm in Orange County, California, where pigs were fed raw garbage, a common practice in those days. The disease spread rapidly so that by the 1950s forty-two states were reporting outbreaks of this new disease. Strains of this virus appear suddenly in animals living in one ocean, and then in subsequent years the same strain will appear in other oceans. While several routes are possible, air, water, and ice may operate in concert to transport this virus temporally and geographically.

In 1992, thousands of people along the coast of Bangladesh began vomiting and experiencing severe dehydrating diarrhea. Many died. The scourge was not new. It was cholera once again, certainly not a surprise to people in this part of the world. What was new was the realization that this epidemic was accompanied by an upwelling of deep-sea water to the surface near the Bangladeshi coast, and the possibility that the cholera pathogen may reside there. Scientists are finding more and more pathogens (e.g., human rotaviruses which cause gastroenteritis), many of which are found only in human feces, surviving at great ocean depths. Do you like to spend a hot day on the beach, with an occasional dip in the lake or ocean? You may want to reconsider. In many shoreline communities of the world, and even in the US, raw or incompletely treated sewage is dumped into these bodies of water. Some ships and boats dump garbage and sewage into the waters of the world. These discharges contain human viral and bacterial pathogens. Infection of even a single person may be enough to start an epidemic of viral or bacterial gastroenteritis or worse. So, there exists a number of mechanisms by which waterborne pathogens of humans, animals, and plants may come onshore to cause disease. Ice may act to preserve these pathogens on a long-term basis, such that they might r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Authors

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 Reaching Backwards

- Chapter 2 Questions and Answers

- Chapter 3 The Importance of Water and Ice

- Chapter 4 The Diversity of Ice

- Chapter 5 Permafrost

- Chapter 6 What Is Life?

- Chapter 7 Fossils: Marking Time

- Chapter 8 Walking into the Past

- Chapter 9 Isolating and Characterizing Microbes from Ice

- Chapter 10 A Brief History of Research on Life in Ice

- Chapter 11 Ice Core Discoveries

- Chapter 12 Subglacial Lake Vostok

- Chapter 13 Discoveries from Other Ice-Covered Lakes

- Chapter 14 Life Is Everywhere

- Chapter 15 Pathogens in the Environment: Viruses

- Chapter 16 Pathogens, Hazards, and Dangers

- Chapter 17 Everything Old Is New Again, the Ultimate in Recycling

- Chapter 18 Astrobiology—Out of This World

- Chapter 19 Disappearing Ice—Global Climate Change

- Chapter 20 Epilogue

- Index