eBook - ePub

Peer-Group Mentoring for Teacher Development

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Peer-Group Mentoring for Teacher Development

About this book

Supporting new teachers is a common challenge globally and the European Commission has recently emphasised the need to promote a lifelong continuum of teachers professional development by building bridges between pre-service and in-service teacher education.Peer-Group Mentoring for Teacher Development introduces and contextualises for an internati

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralPart I

Peer-group mentoring and work-based learning in the teaching profession

This part of the book introduces the theoretical basis of the peer-group mentoring model as a form of work-based learning combining both informal and formal learning experiences.

For understanding the basic tenets of the peer-group mentoring model it is important to understand the context in which the model has been developed: the education system in Finland. As a result, the Finnish culture of teacher education and teacher development is also described.

Dear reader

In this book we shall invite you to reflect on your experiences and ideas related to work-based learning. The book also includes reflection tasks that will hopefully encourage you to embark on a conceptual journey and explore your own history of work-based learning.

We hope that you will first identify where exactly you have learned the skills and competences that you currently apply to your work. How much of your professional competence comes from education? Here you can take into account both degree-awarding education and potential additional qualifications and continuing education. How much do you think that you have learned outside formal educational environments? Have you, for example, learned something essential for your work while reading a newspaper or through a discussion with your colleague? How much have you learned by simply performing your tasks, through personal experience?

Write down your estimates rounded to the nearest 10 per cent. Do not think too long; trust your first instinct. No one will ask you to report on your estimates, just as no one will be able to perform a precise measurement of the amount of learning. It is enough if you try to be honest with yourself.

Based on my experience, I estimate that through education I have acquired approximately _____ % of the knowledge and competence that I use in my job.

Based on my experience, I estimate that outside education I have acquired approximately _____ % of the knowledge and competence that I use in my job.

Chapter 1

Teacher education and development as lifelong and lifewide learning

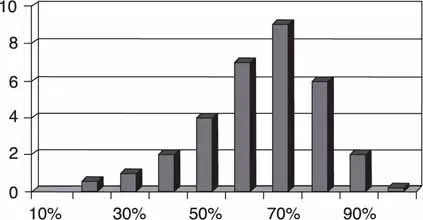

It is common for teachers to acquire part of their core professional skills outside of formal education. We have often posed the questions on p. 2 to teachers who are beginning their mentoring studies, and their answers are typically distributed as Fig. 1.1 shows.

Figure 1.1 Experienced teachers’ estimates of the amount of their learning outside teacher education

When teachers have been asked how – apart from education – they feel they have developed the knowledge and skills essential for their profession, the following have been typical answers:

• through own life experiences

• through own school experiences

• from pupils’ parents

• from pupils’ feedback

• from their own children and family

• from an experienced teacher – and from younger teachers

• from colleagues

• from different informal teacher groups

• from the Internet

• through hobbies

• through school board activities.

We have noticed that when teachers (or other professionals) are asked where they have learnt the most important skills they need in their job, about 70 per cent of the respondents tend to report having learnt those skills at work or somewhere else outside the formal education system (e.g. Tynjälä, Slotte et al., 2006; Heikkinen et al., 2010).

Our findings are in line with international research results. Numerous studies have shown that as a rule as much as 70 to 80 per cent of relevant know-how at work is based on informal and nonformal learning (Fullan, 2001, p. 107; Marsick & Watkins, 1990, pp. 46–48; Kim et al., 2004, p. 40; Pesonen, 2011, pp. 18–19). Merriam et al. (2007) have noted that upwards of 90 per cent of adults are engaged in hundreds of hours of informal learning. This is something that newly qualified teachers do not necessarily recognize. Therefore, it has been suggested that new teachers should be helped to value and utilize the informal learning opportunities that their work offers (Williams, 2003). Similarly, the current trend of emphasizing practice as the crux of teacher preparation (Cochran-Smith & Power, 2010) recognizes the power of learning in authentic work contexts.

The results described above clearly indicate that teaching professionals develop some of their core competences in varying contexts. This is currently a common phenomenon in many other fields as well. People make significant gains in learning in various life situations, not merely within education. Therefore, we usually speak about lifewide learning, which means that learning takes place widely in different life contexts, such as work, free time, and training. In addition to being lifewide, learning is also lifelong. In other words, learning is not restricted to school during childhood and adolescence, but instead continues throughout life. The concept of lifelong learning thus refers to vertical learning that takes place gradually over the course of time. Lifewide learning, in contrast, refers to horizontal learning in different activity contexts.

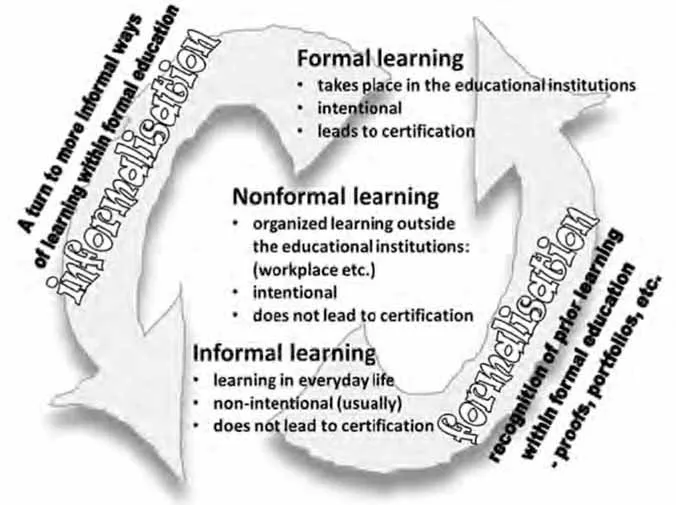

Learning has often been classified into three types (European Commission, 2001; Merriam et al., 2007, pp. 29–30; Tynjälä & Heikkinen, 2011):

1 Formal learning takes place in educational institutions and is intentional in nature. It is highly institutionalized, often even bureaucratic, curriculum-driven, and formally recognized with grades, diplomas, or certificates.

2 Nonformal learning is organized outside of the formal educational system, for example, in the workplace. Learning is also intentional but does not lead to formal certification. This kind of education tends to be short-term, voluntary, and have few if any prerequisites. However, it typically has a curriculum and often a facilitator.

3 Informal learning is usually unintentional and takes place as a side effect of other activities, such as work, in everyday settings.

It is often difficult to distinguish between the above types of learning. For example, success in many jobs requires active information retrieval, which is why the media and the Internet have become increasingly crucial tools of learning in working life. Formal education includes practical training periods in workplaces, and the informal learning experiences gained in this way are utilized in formal learning. This sort of integration of formal and nonformal learning is not new as such – in various versions it has been implemented in all education leading to a profession.

We sometimes hear people claim that theories are of no use at work, with practical competence instead being the decisive factor. However, the division between theory and practice is problematic and to some extent even deceptive. It creates the illusion that theory and practice are two separate entities, even though the study of expertise actually confirms that, in skilled activities, theory and practice are both parts of one entity. This merger of theory and practice is crystallized in Kurt Lewin’s famous phrase: ‘Nothing is as practical as a good theory!’

In light of the aforementioned definitions, reflect on your own learning path for a moment.

• My most memorable experiences of informal learning have been …

• I have experienced nonformal learning …

Informalization and formalization of learning

Formal education frequently applies methods that resemble informal learning. For instance, training events include pair or group discussions through which people can better link their everyday or work-life experiences to the phenomena being addressed. It is also increasingly common to integrate work-based learning, projects, and portfolio work into formal education. Formal learning is consequently enriched by new forms that resemble daily work or a collegial exchange of ideas. In recent years, we have witnessed a trend in formal learning towards a kind of informalization of learning, that is, a move to more nonformal and informal forms of learning. The mushrooming of work-based learning, introduction of ‘lifeplace learning’ (Harris & Chisholm, 2011), and the increasing use of social media (see e.g. Huber, 2010) are examples of this trend of utilizing informal learning also in the context of formal learning.

In quite a few workplaces, the content of work as such equals learning. Today it is not even a question of having to keep up to date in order to manage in one’s job, but rather that the actual tasks change to encompass a larger amount of information processing, and consequently also learning. This kind of work, based on the processing of concepts and symbols, is called symbolic-analytical work. Tasks like this have become more frequent in the information society, in which a teacher’s work has also moved closer to the work of a ‘symbolic analyst’. One important task of teachers today is to provide the learners with symbolic-analytical skills; for example, those related to information retrieval, its critical analysis, and processing through words and symbols.

The development of social media has also changed the forms of learning and contributed to the blurring of formal learning boundaries. For example, it is common for university course participants to form a functioning, informal social media group on Facebook, Ning, or LinkedIn. The communication is often very casual, but it also includes a broad exchange of ideas relevant to learning on the course. With respect to these discussion groups, it is often quite difficult to distinguish what is learning that complies with the course curriculum, and what is something else.

The informalization of learning is a reflection of a major pedagogical trend in our time, constructivism, which is based on the idea that learners construct their knowledge on the basis of their prior views, knowledge, and experiences. In education, it is important to ‘activate’ people’s preconceptions and experiences, so that they can better be linked to the information at hand. The aim is for education to offer such learning situations in which informal and nonformal knowledge are better connected to formal knowledge, through general theories or conceptual models, for example. This is how the information offered through formal learning better meets people’s previous ideas and background experiences, which will promote the learning process and enhance its profundity.

At the same time, there is a trend towards the formalization of informal learning taking place in everyday situations. Methods that enable the recognition of prior learning are being promoted in formal education; they also serve to demonstrate what people have learned in their work and everyday lives. For this purpose we use, for example, skills demonstrations and portfolios. The recognition of different forms of learning has actually become an international trend: the recognition of prior learning as well as the development of tools for systematizing, documenting, and assessing informal and non-formal learning are parts of this trend. This was the leading theme, for example, at the Copenhagen conference of 2008, which was a continuation of the Bologna process that aims to create a common European Higher Education Area (EHEA). One of the main goals of this European process, which started in the 1990s, has been to establish closer links between education and working life.

Two opposite processes thus seem to be taking place at the moment, which are sometimes difficult to distinguish from each other: first, the formalization of informal and nonformal learning; and second, the informalization of formal learning. As a joint consequence of these interconnected and parallel processes, formal, informal, and nonformal types of learning are verging on each other (see Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.2 The dialectics of formalisation and informalisation of learning

Sources: European Commission, 2001, pp. 32–33; Tuschling & Engemann, 2006.

The trends of formalization and informalization can be seen in teachers’ professional learning as well as in other professional fields. While earlier it was typical to distinguish between formal in-service training and informal job-embedded learning, it is now recognized that the organization of teachers’ informal professional learning communities is becoming increasingly structured and formalized, and – at the same time – the formal forms of learning are often integrated with informal learning taking place in teachers’ everyday work (Wei et al., 2009; Siivonen, 2010).

From the viewpoint of what we know about the nature of professional expertise, the trend of blurring the boundaries between formal and informal learning is a welcome one. High-level expertise requires integration between the three basic elements of expertise: formal theoretical or conceptual knowledge; more informal experiential or practical knowledge; and self-regulative knowledge (e.g. Tynjälä, Slotte et al., 2006; Tynjälä, 2008; Heikkinen et al., 2011). Utilizing informal work-related learning in formal training and combining them promotes the integration of the components of expert knowledge. The findings by Wei et al. (2009) suggest that this approach to teacher development is positively reflected in student achievement. They made a comparison of countries that participated in the OECD PISA studies and found a number of common features characterizing professional development practices in the high-achieving countries. These features included extensive opportunities for both formal and informal in-service development; time for professional learning and collaboration built into teachers’ working hours; professional development activities that are embedded in teaching contexts; school governance structures that support teacher involvement in decisions regarding curriculum and instructional practice; teacher induction programmes for new teachers; and formal training for mentors.

In developing teacher education, these forms of learning have been taken into account as action recommendations in many countries. The aim is to create a seamless continuum of teacher education, in which degree-awarding education, the induction phase after graduation, and career-long continuing professional development are linked to one another. In all of these phases, formal, informal, and nonformal learning opportunities are utilized. In addition, the aim is to bring together teaching professionals who are currently in these various phases, and to make them meet each other in different learning situations.

The key idea of this book’s topic, peer-group mentoring, relies on the integration of formal, informal, and nonformal learning, with constructivism as its core principle. Peer-group mentoring resembles learning through informal conversation, in which the participants acquire relevant professional knowledge and develop their skills on the basis of their prior ideas and experiences. However, the group is not just chatting over coffee, as it also aims at explicating what has been experienced and learned; in other words, at raising learning to a conscious and conceptual level. Increased understanding of the challenging situations included in teachers’ work helps one face new situations and develop new solutions. Learning through peer-group mentoring is thus realized through the interaction of practical work and reflective discussions addressing it.

High-quality expertise in any field is not just about individual knowledge and competence (Tynjälä, 2008). For example, in order to be a skilled teacher, it is certainly important to be familiar with teaching methods, curricula, the facilitation of learning, learning theories, and so on. But it is also important for a teacher to recognize knowledge embedded in the operating environment and socially shared practices of the workplace. A significant part of this contextual and collaborative competence implies so-called tacit knowledge, which is not easy to express in words. Mastering this nonverbal social knowledge is a crucial part of teachers’ expertise, which is addressed in peer-group mentoring with the help of joint reflection and discussion.

Induction phase as a challenge in the teaching profession

• What were your feelings when you arrived at your first workplace?

• How were you received?

• How did you learn the practices of the workplace?

The transitional stage from studies to working life is always a challenge, but for teachers it is even more radical than in many other professions. As a rule, careers progress gradually to take on tasks of ever-increasing responsibility, and the employee has time to get accustomed to new challenges over the course of time. Teaching, on the contrary, usually implies the adoption of full juridical and pedagogical responsibility right after graduation. Teaching has, in fact, sometimes been described as a profession with an ‘early career plateau’: teachers face great challenges right at the beginning of their career, but these challenges do not significantly increase later, so long as they do not change career orientation and become, for example, head teachers.

Teachers’ legal responsibilities and rig...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Contributors

- Peer-group mentoring in a nutshell

- PART I. Peer-group mentoring and work-based learning in the teaching profession

- PART II. Empirical studies on peer-group mentoring

- PART III. Towards collegial learning

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Peer-Group Mentoring for Teacher Development by Hannu L. T. Heikkinen, Hannu Jokinen, Päivi Tynjälä, Hannu L. T. Heikkinen,Hannu Jokinen,Päivi Tynjälä in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.