![]()

1

A brief history of landscape research

Marc Antrop

The history of what we now call landscape research followed many different paths and several important conceptual changes occurred. I will consider landscape research in the broadest sense, in keeping with the concept of landscape itself. Scientific landscape research covers both natural and human sciences, but the study of landscape also encompasses the visual arts and applications in landscape architecture, planning and management. Interpreting and understanding the landscape is also achieved through the application of research by design. This research complexity can be understood by considering the multiple meanings of the word ‘landscape’, as well as the broader contexts of society and technology. As the roots of the word ‘landscape’ are found in Western Europe, the perspective of this review will start there.

First, I will discuss the etymology and meanings of the word ‘landscape’ related to the differentiation of activities of studying and forming the landscape. Second, I shall consider the consecutive phases of the history in more detail and comment on different regional developments, illustrated with some examples from North America, Europe-Middle East and Southeast Asia. Third, I shall discuss briefly some of the changes in landscape research since the introduction of formal definitions of landscape, by the World Heritage Convention and European Landscape Convention.

The multiple meanings of landscape

Etymological and linguistic subtleties

The origin of the word ‘landscape’ comes from the Germanic languages. One of the oldest references in the Dutch language dates from the early thirteenth century when ‘lantscap’ (‘lantscep’, ‘landschap’) refers to a land region or environment. It is related to the word ‘land’, meaning a bordered territory, but its suffix -scep refers to land reclamation and creation, as is also found in the German ‘Landschaft’ – ‘schaffen’ = to make. Its meaning as ‘scenery’ is younger and comes with Dutch painting from the seventeenth century, international renown of which introduced the word into English but with an emphasis on ‘scenery’ instead of territory. When ‘land’ refers to soil and territory, ‘landscape’ as ‘organised land’, is also characteristic of the people who made it. Landscape expresses the (visual) manifestation of the territorial identity, which is depicted in the visual arts.

Consequently, in common language, the word ‘landscape’ has multiple meanings and, according to the focus one makes, different perspectives of research and actions are possible. Different linguistic interpretations and translations added to the complexity and resulted in a lot of confusion. Researching the exact meaning of the word and its ‘scientific’ definition dominated the beginnings of landscape research (Zonneveld 1995; Olwig 1996; Claval 2004; Antrop and Van Eetvelde 2017). To clarify the meaning one is using, adjectives were added to the word ‘landscape’, such as natural or cultural landscape, rural or urban landscape or designed landscape. Landscape not only refers to a complex phenomenon that can be described and analysed using objective scientific methods, it also refers to subjective observation and experience and thus has a perceptive, aesthetic, artistic and existential meaning (Lowenthal 1975; Cosgrove and Daniels 1988). The term ‘landscape’ became also a metaphor, as in media landscape or political landscape. Unsurprisingly, the approaches to landscape are very broad and not always clearly defined. Most interest groups dealing with the same territory of land see different landscapes. There are different ‘ways of seeing the landscape’ and its meaning shifts with the context and background of the users (Cosgrove 2002).

Societies with and without landscapes

Based on his observations in Japan, Berque (1982) formulated the theory that two types of societies exist: one without and one with the notion of landscape. Luginbühl (2012) elaborated upon the idea and discussed the intimate relationship between society and landscape, and between the landscape as a tangible reality and its representation. Societies ‘without landscape’ have only a pure utilitarian or symbolic relationship with the land and do not contemplate the landscape as societies ‘with landscapes’ do, which in the latter case results in landscapes being given proper names and in various artistic expressions and representations. For example, the Western way of conceiving of landscape as an aesthetic view of the countryside and its meaning as a territorial unit does not exist in cultures of the Middle East. Makhzoumi (2015) discussed the causes and effects of the absence of the territorial meaning of the word landscape in the Arab Middle East. She explains the absence of the concept by the extreme contrast between a hostile desert environment and the human-made agrarian and urban landscapes where people live. Therefore, the focus of aesthetic appreciation is on enclosed, ordered, constructed cultural environment, with qualities such as comfort, security and beauty. In Farsi, the expressions baghi sazi (‘to make garden’) and muhawata sazi (‘to make enclosure’) are closest to the concept of landscape.

In ancient China, around the year AD 400, the natural landscape was described in poetry using 风景 (‘scenery’). The modern word for ‘landscape’ 景观 was borrowed from Japanese in the early twentieth century, which had a meaning similar to the German ‘Landschaft’. In contemporary Chinese dictionaries, ‘landscape’ has two meanings: that of scenery, prospect or view and that of tangible terrain or topography.

Landscape in visual arts

Sketches and paintings are the oldest representations of landscape features, and during explorations they were as important as the descriptions and measurements made. The two main traditions of landscape art are the Western and Chinese, and both are over a thousand years old. The major difference in landscape painting between the West and East lies in the appreciation and acceptance of the genre. Calligraphy and the classic Chinese mountain-water ink painting (shanshui style) were the most prestigious forms of visual art. The meaning of the landscape in paintings is essentially different between the West and the East. In East Asia, the focus was on spiritual qualities of nature and landscape as a moral inspiration for humans. In Europe, the focus was on painting history with mythological or religious subjects, demanding a spatial setting, i.e., a landscape background. Stylised landscape elements, mainly vegetation, were found on murals. In the fifteenth century, very detailed landscape features appear in manuscript illumination and as background scenery seen through a window. It was only during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that the landscape genre became accepted, in particular in the Flemish and Dutch schools of painting. A commercially successful form was ‘the Small Landscapes’, which are landscape drawings and prints of everyday landscape scenes made by anonymous artists from the Low Countries (Silver 2012). Another successful style was so-called ‘world landscapes’ showing imaginary panoramic scenes from a bird’s-eye perspective, which provided the setting for a myth or legend (Schama 1995). A more scientific variant is found in the oblique topographical views of towns, where the painter became a predecessor of the cartographer. In China, panoramic paintings are an important subset of handscroll paintings. The most famous one is Along the River During the Qingming Festival, painted by Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145) in the Song dynasty, showing in great detail the daily life of people and the landscape of the capital Bianjing, today’s Kaifeng.

Maps can be regarded as tools to describe and study the landscape. Again the difference between Europe and the East is obvious. The Chinese coastline and rivers were already accurately mapped during the Ming dynasty. In Europe, cartography developed with the overseas explorations during the Age of Discovery and became important in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Landscape as art

Landscape painting developed simultaneously with garden design and then later landscape architecture. Paintings, such as those by Claude Lorrain, were used as models for the creation of landscape parks, as illustrated by the work of William Kent, whose creations led commentators to say that landscaping was ‘planting paintings’ (Van Zuylen 1994: 82) and a garden was a ‘three-dimensional painting’ (Steenbergen and Reh 2003: 280). The relationship between painting and gardening is also obvious in the classical Chinese garden design. The garden symbolically reflected nature in a miniaturised landscape and was conceived as a three-dimensional painting in which the visitor could stroll.

The landscape itself became an art form. Gardens and parks constituted holistic ensembles, intentionally designed according to aesthetic rules, ideology, fashion, symbolic meanings and the mastery of the creator. Here also research was involved: research by design.

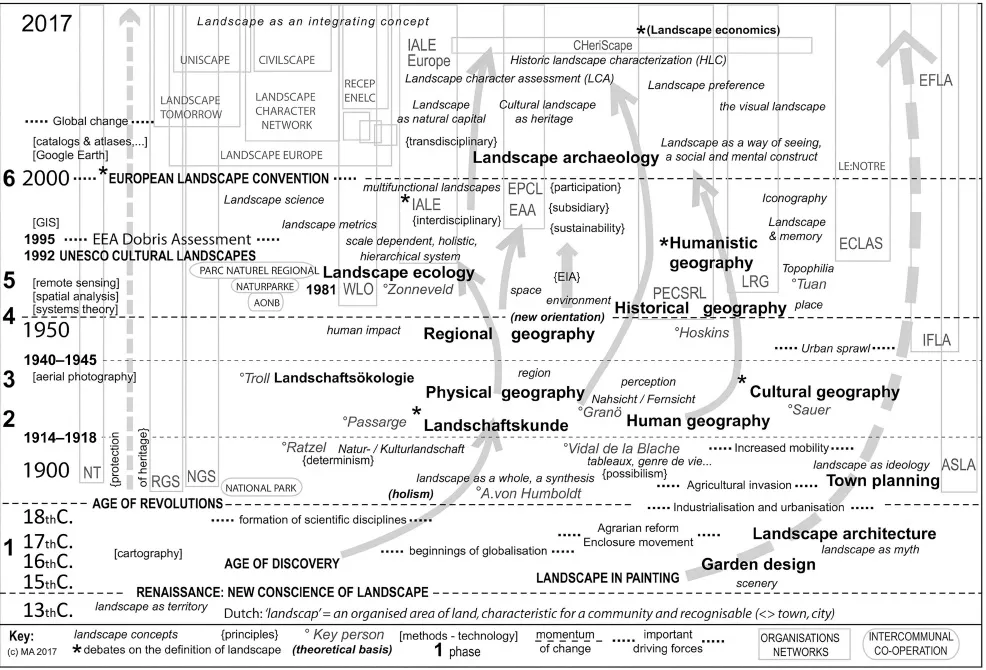

Chronology

Figure 1.1 gives a graphic overview of the history of landscape research from the perspective of Western culture where it originated. It places ideas, concepts, disciplines, methods and technology and exemplary key persons and networks on a time line. No geographical differentiation is attempted to show regional differences. These different aspects are represented by different typographies explained at the bottom of the figure. The different phases that are recognised are indicated by bold numbers on the left and are discussed in greater detail.

Figure 1.1 Development of landscape research.

The early beginnings

Dealing with the landscape as an object of study started in Europe during the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery. In the fifteenth century appeared the first pictorial representations of landscapes, emphasising its visual character and scenery and using the landscape as an expression of human ideas, thoughts, beliefs and feelings. The creation of imaginary landscapes appeared almost simultaneously with a new style of garden design and urban lifestyle. Garden architecture and urban planning made a branch of practitioners from which contemporary (landscape) architecture and town planning developed.

Simultaneously, the discovery of new worlds demanded new methods for describing and depicting in a systematic ‘scientific’ way exotic landscapes and people. New techniques were developed such as cartography.

Emerging scientific research – landscape as an object of study of geography

Philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment initiated the scientific research of the landscape, in particular, Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). Between 1756 and 1796, he gave lectures on (physical) geography and anthropology, two disciplines he considered ‘pragmatic knowledge of the world’ (Weltkenntnis) (Elden 2011). The empirical scientific research of landscape started with the systematic descriptions during naturalistic explorations, such as the ones made by Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) and Charles Darwin (1809–1882). Von Humboldt studied nature as a whole, consisting of the physical and living environment of which humans were a part and therefore culture and history were important as well. He was a pioneer in physical geography, biogeography and climatology, but always spoke about nature. He only used the word landscape as ‘one of the incitements in the study of nature’, in particular, ‘the aesthetic treatment of natural scenery’ in literature and in ‘landscape painting’ (von Humboldt 1849). He also considered the aesthetic qualities of the landscape to be mentally healing (Nicholson 1995). Nevertheless, a short and very concise and often cited definition of landscape was attributed, but not proven, to Alexander von Humboldt: ‘Landschaft ist der Totalcharakter einer Erdgegend’ (Zonneveld 1995). This definition implies that regional diversity is expressed by landscapes and that landscape is a holistic phenomenon which is perceived by humans.

Alwin Oppel, a German geographer, introduced the term ‘Landschaftskunde’ (‘landscape science’) in 1884 (Troll 1950). Theoretical concepts and mainly descriptive methods of this ‘Landschaftskunde’ were developed mainly in Central Europe and Scandinavia. Siegfried Passarge wrote extensive manuals (Passarge 1919/20, 1921/30).

The Finnish geographer Johannes Granö made the distinction between the ‘Nahsicht’ and the ‘Fernsicht’ or ‘Landschaft’ (Granö 1929). The ‘Nahsicht’ (‘proximity’) is the surroundings that can be experienced by all senses, while the ‘Landschaft’ is the part that is mainly perceived visually. He developed descriptive methods for the study of both. He was also a pioneer in photography and introduced this technique of recording in natural sciences, mastering it as an artist (Jones 2003). Most of his work remained unknown until the English translation of his book Reine Geographie as ‘Pure Geography’ in 1997 (Granö and Paasi 1997).

Paul Vidal de la Blache (1845–1918), a French geographer, had a more literary and historical approach to landscape, although he used similar techniques of annotated sketches and his prose was not so different from von Humboldt’s. The main difference was the recognition of the importance of the local society and its lifestyle (‘genre de vie’) in organising the landscape, which resulted in a regional differentiation not only based upon natural conditions but also upon culture, settlement patterns and social territories. He also considered the landscape as a holistic unity, which was expressed in characteristic ‘pays’ (Claval 2004). The description of regions became synthetic ‘tableaux’ of idealistic landscapes. Both von Humboldt and de la Blache implicitly included the perception of landscape and its aesthetic qualities in their work.

Carl Sauer introduced (the German concept of) landscape in the US and made it the cornerstone of cultural geography (Sauer 1925). However, Richard Hartshorne (1939) considered landscape as a territorial concept to be confusing, and redundant, with concepts of region and space being preferable alternatives (Muir 1999). However, Sauer’s vision resulted later in the first important symposium on Man’s Role in the Changing Face of the Earth (Thomas 1956).

The landscape thus became a core topic in geography and was seen as a unique synthesis between the natural and cultural characteristics of a region. To study the landscape, information was gathered from field surveys, ma...