This is a test

- 338 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Performance in a Militarized Culture

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The long cultural moment that arose in the wake of 9/11 and the conflict in the Middle East has fostered a global wave of surveillance and counterinsurgency. Performance in a Militarized Culture explores the ways in which we experience this new status quo. Addressing the most commonplace of everyday interactions, from mobile phone calls to traffic cameras, this edited collection considers:

-

- How militarization appropriates and deploys performance techniques

-

- How performing arts practices can confront militarization

-

- The long and complex history of militarization

-

- How the war on terror has transformed into a values system that prioritizes the military

-

- The ways in which performance can be used to secure and maintain power across social strata

Performance in a Militarized Culture draws on performances from North, Central, and South America; Europe; the Middle East; and Asia to chronicle a range of experience: from those who live under a daily threat of terrorism, to others who live with a distant, imagined fear of such danger.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Performance in a Militarized Culture by Sara Brady, Lindsey Mantoan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performance Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Sites of Conflict

1

Mises-en-scène of Militarization

Decommissioning US Military Infrastructure in the Panama Canal Zone

“Panama will always be surrounded by the ghosts of military bases.”

Sociologist Raúl Leis (in Lindsay-Poland 2003–205)

Figure 1.1 City of Knowledge, Panama, in August 2010. Photo by Katherine Zien.

Introduction

“Only a few minutes away from Panama City, and strategically located alongside the Canal!” intones the narrator of a video advertisement for the City of Knowledge (la Ciudad del Saber), a 300-acre campus hosting universities and NGOs (Ciudad del Saber 2014). As the camera pans over the grounds, the narrator describes the conversion of this former US military base, Fort Clayton, into “a thriving international community where academic, scientific, humanistic, and corporate institutions collaborate to further human and sustainable development based on knowledge.” Clayton’s “old barracks and […] military facilities have been transformed into modern offices, laboratories, and classrooms […] to create a favorable environment for research, learning, innovation, creativity, and interaction” (ibid). For those who knew the area before its transformation, the City of Knowledge departs little from Clayton’s layout: imposing terracotta and stucco structures built between the 1930s and 1950s, with sloping pagoda-like roofs that create a not-unintentional orientalizing effect, seem to float atop pristine, palm-lined grounds.

The video juxtaposes sepia-toned vintage photographs of Clayton with colorful present-day images of the red and cream buildings, where multicultural groups gather for conferences and gaze out at the dawning of a proverbial bright new day.

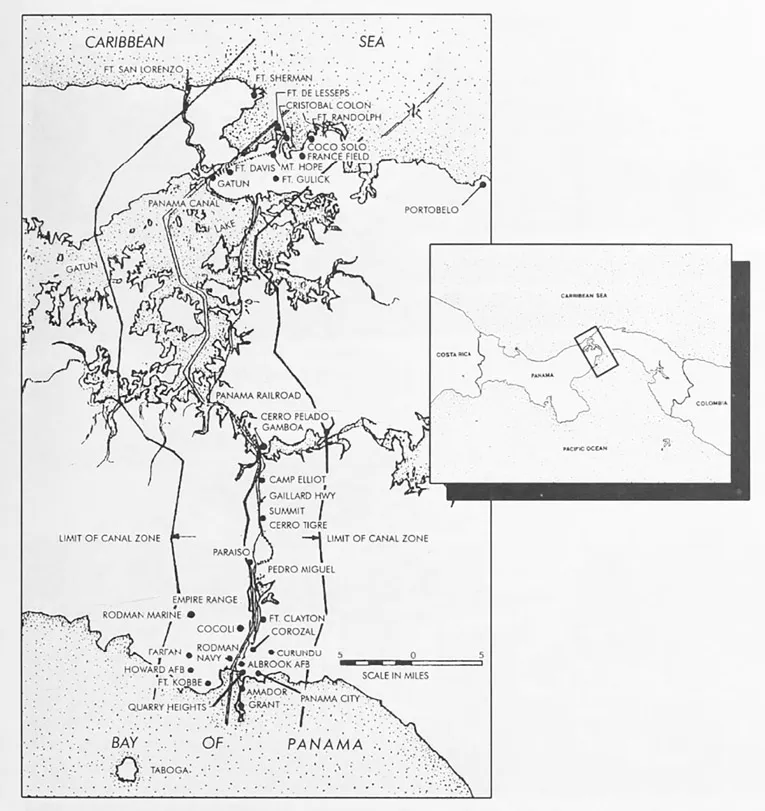

Clayton is one of many former US military installations repurposed by the Republic of Panama. Ratification of the Torrijos-Carter Treaties (1977–1978) set in motion the Panama Canal handover, a process whereby the US government returned the Canal and its surrounding Canal Zone—a 553-square-mile territory occupied by the United States since 1904—to Panama. The Panamanian government made plans for the reuse of the Canal Zone’s terrain and infrastructure, transferred between 1979 and 1999 (Figure 1.2 shows a map of US military installations in Panama). One of Panama’s primary goals was to make all former US military sites civilian. The Pentagon had sought to retain some bases after 1999, but this effort was quashed in part by a Panamanian civil society outraged after decades of foreign military occupation (Lindsay-Poland 2003:188). As Clayton and other bases were converted to civilian uses, the Panama Canal’s handover was hailed as both decolonization and demilitarization. The former bases have met multifarious ends since their reversion. Near the City of Knowledge is the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, formerly a US Air Force installation. A luxury resort hotel owned by the Melía Corporation occupies the grounds and buildings of the former United States Army School of the Americas (USARSA, or SOA) (1949–1984), where US officers trained many of Latin America’s military and paramilitary forces in counterinsurgency tactics including torture, terror, espionage, and the use of US-manufactured weapons (Gill 2004). Apart from the bases that were rehabilitated and given new contexts (Clayton and Gulick), other sites were razed (Amador) or left to squatters and rot (Coco Solo). There is no overarching narrative in which to situate these sites’ transitions; the sole link is their demilitarization.

It is understandable that Panama’s government has little incentive or desire to preserve these sites’ military pasts. Because US occupation of the Canal Zone went hand-in-glove with militarization, Panamanian leaders feel that the bases’ histories are not part of Panama’s national narrative—a trajectory marked by independence from Colombia in 1903, and sovereignty over the Canal in 1999. In repurposing these sites, the Panamanian government has framed their conversion as a sharp break with the past—and with militarism. While retaining the bases’ physical structures, the Panamanian government seeks to intervene in and alter the embodied ways that people interact(ed) with the sites. The areas, formerly off-limits to many Panamanians, are now declared peaceful and accessible (at least to those who can afford to lease or buy property there)—a process felt to be crucial to the recuperation of Panama’s post-colonial sovereignty.

Figure 1.2 Map showing historical bases in the former Canal Zone. Panama Canal Museum Collection, Special and Area Studies Collections, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

The conversion of that which I am calling the “former military Zone,” while highly laudable, tends to omit the intimate histories of relationships between base personnel and Panamanians, although these histories cannot be preserved or commemorated easily. The former military Zone was, in fact, host to daily micro-interactions of thousands of workers, soldiers, and dependents. Many people in Panama and the United States remember this military Zone positively. Indeed, the bases were, by and large, not spaces of violence: rather, they hosted exchanges, pedagogy, training, and transfers of military technique—crucially, through modes of performance, in combat simulations—that were intended for use in “other” sites. With notable exceptions in 1964 and 1989, the Panamanian isthmus did not see direct combat. Rather, the former military Zone functioned as a series of “staging areas”—sites of simulation, representation, and deferral (Donoghue 2014:177). Even if Panama or the United States wanted to preserve their history, what might it mean to commemorate a “staging area,” or represent scenography?

The bases’ peaceful conversion also reinforces a military-civilian divide. After the 1989 US invasion, Panama moved to officially eliminate its standing army. The gap between the isthmus’s military past and civilian present echoes mainstream attitudes in the contemporary United States, whose “civilian population,” broadly writ, experiences a sense of estrangement from military affairs, even as the US military “has been engaged in the longest period of sustained conflict in the nation’s history” (Pew 2011). A Pew Research Center report notes that “just one-half of one percent of American adults has served on active duty at any given time,” and enlistment numbers are at their lowest ebb since the interwar period (ibid). Several scholars and journalists examine the widening gap between civilian and military realms, which has become apparent in varying styles of US media coverage and political discourse over the past decades (see Lutz 2009; Gill 2004; Lindsay-Poland 2003:204; Cloud and Zucchino 2015). The Panama Canal Zone’s military infrastructure has, in fact, played a crucial role in constructing and elaborating military-civilian divides on the isthmus and in the United States. As I discuss below, military “staging areas”—located in a Canal Zone framed as both part of and separate from the domestic United States—have allowed US civilians to see the theatre of combat as simultaneously near and distant, violent and peaceful.

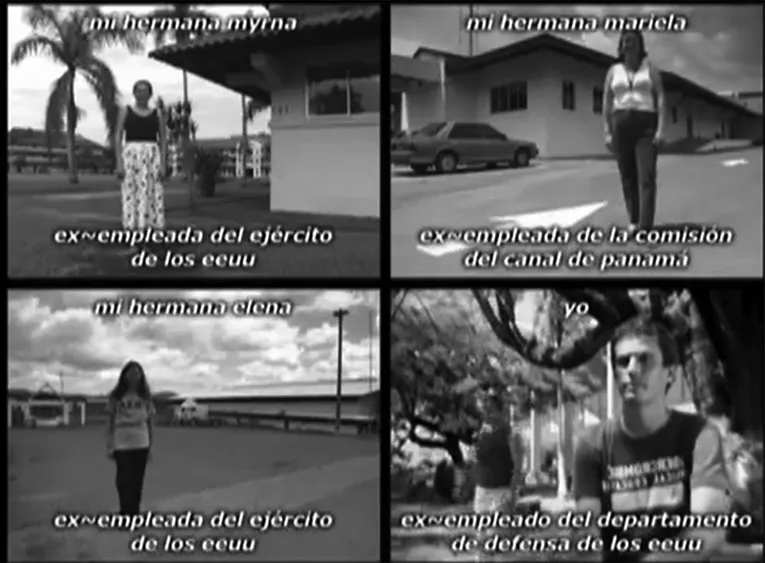

An analysis of the former military Zone proves the impossibility of divorcing civilian from military strands, however. Praised for its demilitarization, the Zone hosted many civilian functions, conditions, and relationships of domesticity, humanitarianism, leisure, sport, and entertainment alongside its pedagogies of torture, espionage, US-supported proxy wars, chemical weapons testing, military-industrial alliances, and drug trafficking. Panama was strongly connected as a service center with ideological ramifications: as sites of trans-national anti-Communist collaboration, the bases employed thousands of Panamanians. Even at their ebb in 1999, they brought in $249 million US dollars to Panama’s national income (Lindsay-Poland 2003:178). One of the artists whose work I address below, Enrique Castro Ríos, prominently displays this intimate military-civilian braid in his film Familia (Family, 2007), which includes vignettes of Castro Ríos and family members formerly employed by the military Zone (see Figure 1.3).

Despite the semblance of a break between (foreign military) past and (civilian nationalized) present, the bases’ afterlives continue to “ghost” their contemporary moment. Temporal lags emerge in Panamanians’ naming practices for the ex-bases. While foreign visitors might find the City of Knowledge beautiful, many locals have difficulty envisioning it as anything other than a US military base, off-limits to them for roughly 50 years. Many Panamanians still refer to these areas by their US military names: “City of Knowledge” is still frequently called “Clayton”; a Panamanian friend observed that the US Army was replaced by a “UN Army” of bureaucrats. The late Panamanian sociologist Raúl Leis noted that Panamanians often felt a sense of disorientation and anxiety on entering the Zone, before and after its handover; he called this phenomenon “venganza inconsciente” (unconscious revenge) (Leis 2010). Even as the former bases have been converted to diverse ends, their pasts persist in haunting mises-en-scène, environmental pollutants, and memories—fond and troubling—that reside in the bodies and affects of people who lived and worked in and around them.

Figure 1.3 Screenshot from Familia (Family, 2007), listing Enrique Castro Ríos and family members as former US Department of Defense employees. Courtesy of Enrique Castro Ríos.

Rather than constituting a deficiency, these uneven adjustments to the break are crucial rem(a)inders of the difficulty or impossibility of excising militarized components from spaces concertedly being reframed in the public imaginary as civilian and peaceful. Embodied pasts cling: the sites are sticky with meanings continuously (re)activated by those who remember and retell their histories of connection. Embedded in Panama’s temporal and political discourse of regained sovereignty are other disavowed, continuous histories of the former military Zone. These histories reveal the workings of coloniality—structures of racial and social inequality, modernity’s “dark side,” that do not end with decolonization (on coloniality, see: Mignolo 2011; Moraña, Dussel and Jáuregui 2008). Much like performance scholar Joseph Roach’s concept of “surrogation,” coloniality persists through distinct performers inhabiting comparatively stable roles (Roach 1996:2–3).

Militarization in/as Performance

An analysis grounded in performance, then, can bring to the fore the embodied interchanges through which the former military Zone fostered a multitude of lives on the isthmus and in the United States. By reintroducing histories of bodily and affective contact that structured life on the bases, a performance-linked (re)definition of militarization can help to dissolve the constructed binary segregating civilian and military spheres. Citing performance theorist Rebecca Schneider, I note the former military Zone’s “inter(in)animation” of “body-to-body transmissions” of affect, gesture, and relation—normative rituals and everyday performativity—with the material structures that contained and shaped these myriad encounters (Schneider 2011:7, 104). The bases’ architecture and infrastructure conditioned in their users what Schneider calls performances of “modes of access,” or “experiential relations to knowledge” (104–05). Expanding upon Schneider’s work, I note that the bases’ architecture operates scenographically, encompassing both movement and materiality, aesthetics and sociality, to script behaviors and interactions past and present. Embodied and physical components alike contribute to shaping the bases’ “architecture of social memory” (Schneider 2011:99–100).

Redefining militarization in light of performance also allows us to avoid fetishizing militarism’s violence (on distinctions between militarism and militarization, see Lutz 2002:725). Militarization is a process predicated upon the interpenetration of military and civilian behaviors, styles, and realms. Such processual interpenetration inheres in the OED’s definition of militarization as “the action of making military in character or style; […] transformation to military methods or status” (emphasis added). Military historians and performance scholars including Catherine Lutz, Cynthia Enloe, and Tracy C. Davis define militarization as a permanent state of readiness for war, even of rehearsing security and defense (see Enloe 2000; McEnaney 2000; Lutz 2001 and 2009; Davis 2007; Dudziak 2012; MacLeish 2013). Enloe characterizes militarization as a process that can transform nearly anything, even the most civilian-seeming objects and subjects. In particular, she explores the influences of militarization on women’s lives on the “home front,” often (and inaccurately) construed as war’s opposite. Historian Michael Geyer calls militarization the “social process in which civil society organizes itself for the production of violence” (in Gillis 1989:79). These accounts, focusing on possible futures of attack, reveal performance’s subjunctivity—“as if”—to be a central component of militarization’s spatial and temporal imaginaries.

If militarization embeds performance and functions scenographically, then we must reassess the former military Zone in light of the embodied interactions that it has hosted. This angle of approach reveals the Zone’s performance of transnational histories of military-civilian exchange, destabilizing national categorizations and neat narratives of (military) past and (civilian) present. The bases’ scenographic architecture and infrastructure are rem(a)inders of the challenges that attend a post-colonial move to reclaim—and condemn—former US military sites while disavowing their embeddedness in a Panamanian past (and present). The artists whose work I approach in the essay’s latter section—Enrique Castro Ríos and Dalida María Benfield—explore Panama’s histories of US military occupation through techniques of embodiment, site-specificity, and performance, to foreground the sites’ intertwinement of military and civilian, US and Latin American histories, and to reveal structures of coloniality occluded by discourses of demilitarization. Illuminating embodied histories of relation, as Castro Ríos and Benfield do, can bring war close and ground it in the everyday, opening distinct paths and “modes of access” to the former military Zone, to “resituate the site of any knowing of history as body-to-body transmission” (Schneider 2011:104). Perhaps performance offers a way to subvert or undo a story of the former bases that hinges upon decolonization and national independence, with the implicit temporalizing refrain: “Once theirs, now ours; once war, now peace.”

Panama’s “Guns of Peace”: Building a Military-Civilian Divide

The performance of a military-civilian divide has been central to Western hemispheric militarization, and the US government’s construction, and occupation of the Panama Canal from 1904 to 1999 played a significant role in this history. The US government’s occupation of the Panama Canal Zone by treaty, beginning in 1904, enabled the Zone’s tra...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- List of figures

- List of contributors

- Preface: Performance in the Age of Intelligent Warfare

- Introduction: In the Absence of the Gun: Performing Militarization

- PART I Sites of Conflict

- PART II Militarized History and Memory

- PART III Performing the Soldier

- PART IV The Militarization of the Everyday

- Afterword: Constitutive Performances: Human Rights in a Militarized Culture

- Index