A Gendered Profession

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

A Gendered Profession

About this book

The issue of gender inequality in architecture has been part of the profession's discourse for many years, yet the continuing gender imbalance in architectural education and practice remains a difficult subject. This book seeks to change that. It provides the first ever attempt to move the debate about gender in architecture beyond the tradition of gender-segregated diagnostic or critical discourse on the debate towards something more propositional, actionable and transformative. To do this, A Gendered Profession brings together a comprehensive array of essays from a wide variety of experts in architectural education and practice, touching on issues such as LGBT, age, family status, and gender biased awards.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Practice Politics Economics

One

Six Myths about Women in Architecture

The Research

The Myth of Architecture: ‘If you are Talented and Work Hard you will Succeed’

Gender is not a Women’s Issue

Six Myths about Women in Architecture

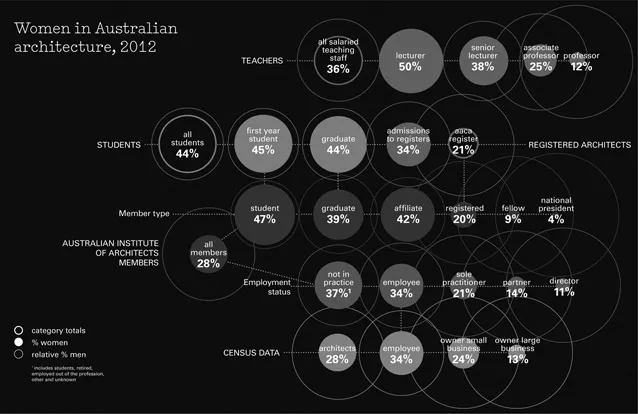

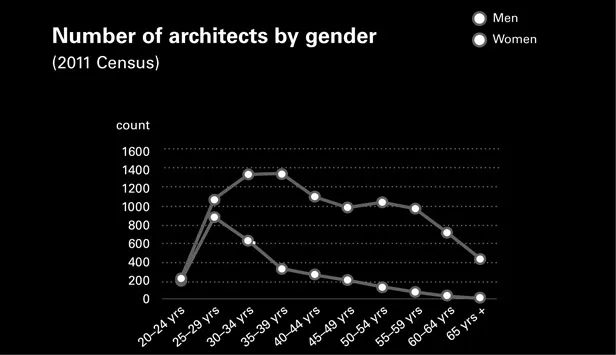

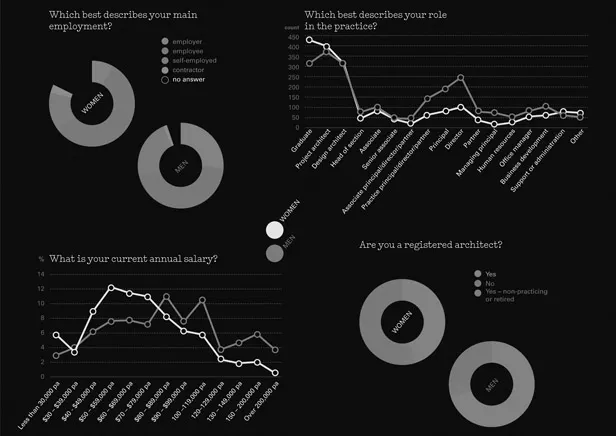

Myth 1: There is no Issue for Women in Architecture

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- CONTRIBUTOR BIOGRAPHIES

- EDITORIAL

- PART 1 PRACTICE, POLITICS AND ECONOMICS

- PART 2 HISTORIES, THEORIES AND PIONEERS

- PART 3 PLACE, PARTICIPATION AND IDENTITY

- PART 4 EDUCATION

- INDEX

- PICTURE CREDITS

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app