![]()

1

New York City, Birthplace of William James

1. New York City, 1842

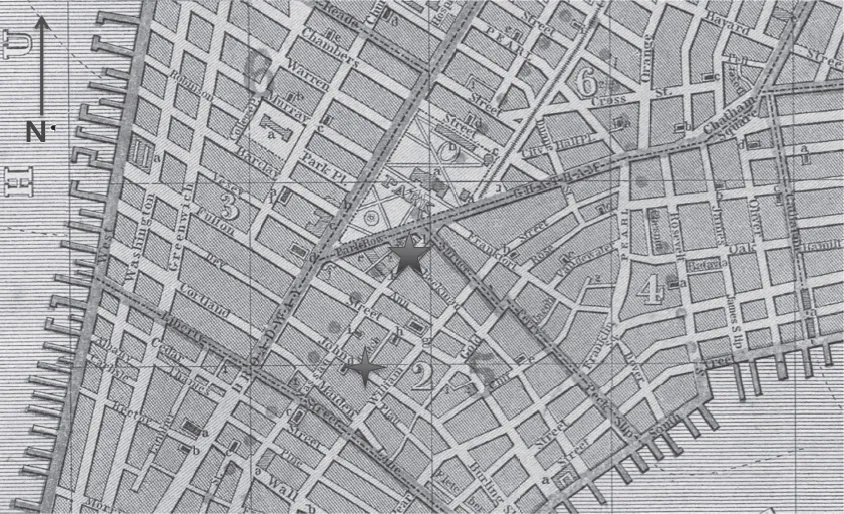

Mary Cecilia Rogers did not return home the evening of Sunday, July 25, 1841. That morning, she had gone out for a walk. She left the home where she lived with her widowed mother, Phoebe, at 126 Nassau St.1 It was in the lower east side of New York City, just a block south of City Hall Park (see Figure 1.1). She said that she would return that evening.2 But she did not.

According to some initial reports, she was seen meeting a young man at Theater Alley, just a block west of her home. The two of them then headed toward Barclay St., the western end of which was known as the dock for the ferry to Hoboken, NJ. According to the report of her fiancé, Daniel C. Payne, however, she had arrived at the room he rented four blocks south of her home, at 47 Johns St., at about 10 a.m. She told him that she was to meet her cousin, a Mrs. Downing, who lived on Greenwich St.3

By Monday, some of Mary Rogers’ friends arranged to have a notice of her disappearance placed in the Tuesday newspapers. It was on Wednesday that her body was discovered floating in the Hudson River just off of Castle Point in Hoboken, NJ (today the home of Stevens Institute of Technology). “It was evident,” the nascent New York Tribune reported, “that she had been horribly outraged and murdered.” The article went on to note that Miss Rogers “was a young woman of good character, and was soon to have been married to a worthy young man of this City.”4

It was the New York Herald (then in its sixth year of publication), however, that took the lead in publicizing the story. On 4 August it declared:

How utterly ridiculous is all this! It is not nearly a week since the dead body of this beautiful and unfortunate girl has been discovered, and yet no other steps have been taken by the judicial authorities, than a brief and inefficient inquest by [Hoboken coroner] Gilbert Merritt. One of the most heartless and atrocious murders that was ever perpetrated in New York, is allowed to sleep the sleep of death—to be buried in the deep bosom of the Hudson.5

Figure 1.1 Map of Lower Manhattan, 1842. Note City Hall Park near the center of the image. Mary Rogers lived near the corner of Nassau and Beekman (5-pointed star). One report said she met a man at Theatre Alley (the narrow unlabeled street just above the star that runs from Beekman to Ann between Nassau and the park), and then the two of them crossed the southern tip of the Park (upwards on the map) to Barclay St., heading toward the Hoboken Ferry dock, another four blocks west. Her fiancé, Daniel Payne lived 3 blocks south and 1 block east, on John St. near Dutch St. (4-pointed star).

The newspapers made the story of Mary Rogers’ murder a sensation for the people of New York. Until the 1830s, newspapers had been rather elite affairs with titles like the Courier and Enquirer, and the Journal of Commerce.6 These publications had small circulations, typically less than 2,000, and they were aimed primarily at the business community: they covered mostly shipping, markets, and national political affairs. They also cost six cents a copy, which put them out of the reach of most working New Yorkers. A few politically radical workers’ papers had come and gone, but they had not earned the loyalty of ordinary New Yorkers. Then, in September of 1833, a printer named Benjamin Day, who had worked on one of the radical papers, the Daily Sentinel, conceived and launched an entirely new kind of newspaper that focused on local news—especially scandal, crime, the police, and the courts. Following the example of the wildly successful Penny Magazine in the UK, he set the price of his new paper at one cent. He called it the New York Sun, which proclaimed on its front page: “It shines for all.” Unlike the radical papers and the business sheets, the Sun did not take an official partisan stand. It did not reflexively denounce prominent members of the “opposing” party. Although the Sun tended Democratic, its stance was as defender of the city and its people. To circulate the new paper, Day had “newsboys,” often drawn from the local orphanages, sell most of the papers on the streets of New York, offering them in bundles of 100 copies for 67¢. Any newsboy who sold all his papers would earn himself 33¢ a day.

The Sun was wildly successful. Within just a few months, it had the highest circulation in the city, at over 4,000. By 1835 its circulation was 15,000. Soon, others began to copy Day’s formula. One of these was the New York Herald, launched in 1835 by a Scottish immigrant named James Gordon Bennett. Looking for a niche outside of the Sun’s sphere, the Herald was pitched at a slightly elevated tone. Unlike the Sun, the Herald included business news, though of a different cast than in the old commerce papers. It became known for its exposés of crookedness and incompetence among New York’s mostly unregulated companies and markets. The paper also displayed Bennett’s own anti-Catholic and anti-abolitionist streaks, tending toward support for the “Know-Nothings” politically, though it was not as extreme as they in its view of immigration (Bennett being an immigrant himself). When the market crash of 1837 threw many of the city’s residents out of work, sometimes out of their homes, the Herald played to the crowd by running scolding accounts of the lavish parties that New York’s rich were still throwing for themselves while the rest of the city suffered. The result was an organized boycott of the paper by the city’s “high society” which damaged Bennett’s Herald, but did not break it.7

The boycott did, however, open a niche in the city’s journalistic ecology for a “respectable” Whig paper that focused on news of the city, but was rather more respectful of municipal powerbrokers. That niche was filled, from April of 1841, by Horace Greely’s New York Tribune. The Tribune did not kowtow to the city’s elites, but neither did it go out of its way to tweak them. It covered crime, but not in the salacious tones of the Sun.

The murder of Mary Rogers rapidly became a cause célèbre for New York’s papers, especially for the Herald. For a woman just 21 years of age, Rogers was already well known in the city as the “beautiful cigar girl” (or ‘segar’ as some had it). She held a job at a fashionable tobacco shop, owned by one John Anderson, located on Broadway. It was a popular hangout of many Tammany Hall politicians and other Democratic Party figures (which may well have played a role in the Know-Nothing Herald’s decision to take the lead in demanding that more be done to find the killer). The proximity of Anderson’s cigar shop to City Hall and to “Publisher’s Row” made Rogers a familiar figure to many New York politicians and journalists.8

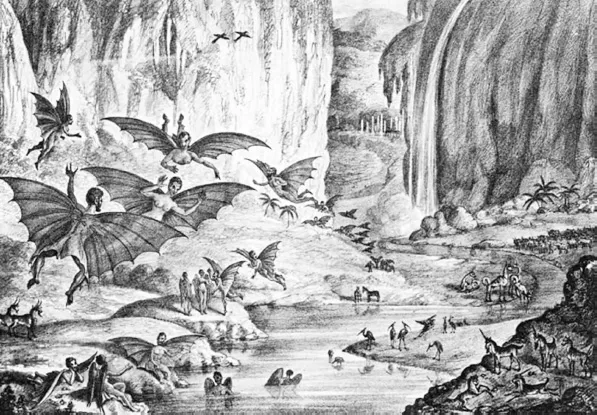

Nearly three years before Rogers’ death, in October of 1838, she had become the object of city-wide attention when the Sun reported that she had disappeared from home, leaving a suicide note behind. Two weeks after her disappearance, however, another newspaper found that she had only visited a friend in Brooklyn, and it accused the Sun of authoring a hoax for the sake of publicity, a stunt that would not have been entirely out of character. In 1835, just two years after its launch, the Sun ran a piece claiming that the great English astronomer, John Herschel, had discovered of a range of fantastic beings living on the moon. The article was, of course, a transparent bid for attention that came to be known as the Great Moon Hoax (see Figure 1.2).

Despite the explanation that Rogers had simply gone to Brooklyn for few days, rumors persisted that Rogers had eloped with a sailor,9 so the insistence by the Tribune (cited above) that she was a “young woman of good character” was aimed at making a specific point with readers who recalled the earlier incident. By the time Rogers disappeared again in July of 1841, her acquaintance with many newspapermen and politicians may have garnered her story much more attention than it might have received otherwise. The mayors of the day—Isaac Varian and his successor Robert Morris, both Democrats—personally took part in the interrogations of various suspects and witnesses. Murder was a relatively rare event in the New York City of 1841.10 In the first six months of 1841, for instance, there had been four convictions for “manslaughter,” and two more for “assault and battery with intent to kill” but none for murder.11 Murder of a “respectable” young woman was rarer still.

Soon after the discovery of Rogers’ body, a string of suspects and witnesses were hauled in for interrogation. Two men were arrested on August 4, along with a sailor. All were soon discharged, however.12 Another sailor was questioned on August 5, also discharged.13 One suspect was pursued as far away as Worcester, Massachusetts and brought back to New York to face investigation. Although it was true that he knew Rogers from the cigar shop, and that he had recently been seen with a young woman on Staten Island, he turned out to have no connection to the Rogers murder.14 The story received an additional salacious boost when it was revealed that Rogers had a former fiancé, a lawyer named Alfred Cromeline, whom she had recently left for Daniel Payne. Two days before her disappearance, Rogers had written to Cromeline asking him to visit her at home. He had declined to do so, saying he had been “coldly received”15 at the Rogers’ home on an earlier visit since their breakup. The next day her name “was written on Cromeline’s slate”16 (presumably at the door of his residence) and a rose was placed in his keyhole. The possibility that the murder was a result of a love triangle began to circulate.

Figure 1.2 Engraving that accompanied the New York Sun’s “Great Moon Hoax” article of August 25, 1835.

As early as August 9, just over two weeks after the murder, the supposition that a gang of men might have been responsible started to take hold. The Herald reported an unrelated story of a Baltimore woman being snatched from the company of a “gentleman” by “eight or ten young men & ruffians.” It then asked rhetorically,

Can this outrage throw any light on the murder of Mary Rogers? … We hear of no clue arrived at, and but very little exertion made for the discovery and punishment of the brutal ravishers and murderers. Let a public meeting be set a foot, a subscription raised in order to offer a reward for the murderers [note the presumed plural] of Mary Rogers. We will give FIFTY DOLLARS; and we doubt not that in less than 24 hours a thousand dollars may be raised, to be paid into the hands of the Mayor of New York, for the purpose of stimulating the energetic and indefatigable police.17

The solicitation of money for a police investigation was hardly incidental. In 1841, New York did not yet have a modern professional police force. On the streets, there were just two elected, unpaid constables per ward to watch over the city during the day. At night there were dozens of poorly paid watchmen (“leatherheads,” as they were often called) who were political appointees. The inducement for corruption could hardly have been greater. Neither the constables nor watchmen were trained full-time policemen. They mostly did their law enforcement “on the side,” and both groups tended to pay attention to investigations that came with...