![]()

1

Overview and introduction

Most of economics takes politics for granted. Through some (often implausible) assumptions, it seeks to explain away political structures by characterizing them as stable and predictable, or as inconsequential to understand what goes on in an economy. To someone like me, who grew up in Italy during a time when there was a new government almost every year and politics permeated virtually every aspect of daily life, such attempts are misguided.

Governments and other political institutions, far from being unchanging and benign monoliths, are composed of people who respond to incentives and whose behavior and choices can be studied through the lens of economics. And this book aims to do exactly that: to examine and explain the choices of politicians and governments, starting from the level of individuals and building up to equilibria. Using the tools of microeconomics, we will take many of the concepts you may have already seen—preferences, technology, endowments, and market equilibria, among others—and apply them to the political realm: a broad enterprise that we will call political economy.

As is often said, it is only possible to see further if one is standing on the shoulders of giants. Before we begin our study of political economy we will want to learn about some of the great thinkers who paved our way. When Adam Smith, father of modern economics, published The Wealth of Nations in 1776 there was no conceptual distinction between politics and economics. In as much as you will study John Stuart Mill, David Ricardo, Thomas Malthus, and others in courses on the history of economic thought, it should be noted that these thinkers were very much considered writers on ‘political economy’ in their time. This makes good sense, since in the 18th and 19th centuries these thinkers lacked many of the tools and knowledge—now

integral in the social sciences—necessary to separate political processes from economic ones. They could scarcely imagine the insights of modern psychology, sociology, and political science, much less the mathematical rigor that was added to the study of economics in the 20th century by pioneers like Paul Samuelson.

Figure 1.1 Overview: 1776–1900.

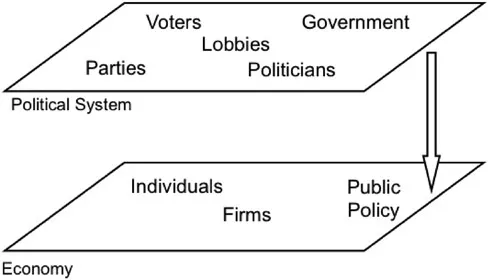

Indeed, that added rigor marked the first major transformation for political economy. Between 1900 and 1980, economists from the United States and Europe devised formal ways of expressing economic and political concepts mathematically using calculus and statistics. The problem, however, was that oftentimes the mathematical expressions relied on drawing stark and simplistic contrasts between the political and economic realms. For example, in the 1950s, Kenneth Arrow, Gerard Debreu, and Lionel McKenzie developed the powerful formal framework of general equilibrium theory but excluded politics from their analysis. They sought to characterize economic equilibria by relegating political factors to considerations that were outside of their models; it is as though there is a vector of policy parameters, θ, with which we ask what, conditional on θ, we can surmise about an economy, with the implicit understanding that policies are somehow determined by political forces that operate outside of the economy. Roughly at the same time, the pioneering work of economists Anthony Downs, James Buchanan, and Gordon Tullock did exactly the opposite, by focusing on political outcomes as the equilibrium objects of their analyses grounded in the realm of politics, while regarding economic phenomena as ‘nuisance parameters’ coming from the totally separate realm of economics.

Yet we know that we are not born operating on two distinct planes, one political and the other economic. It is not as though political parties and politicians are from Mars while firms and consumers are from Saturn. Our challenge

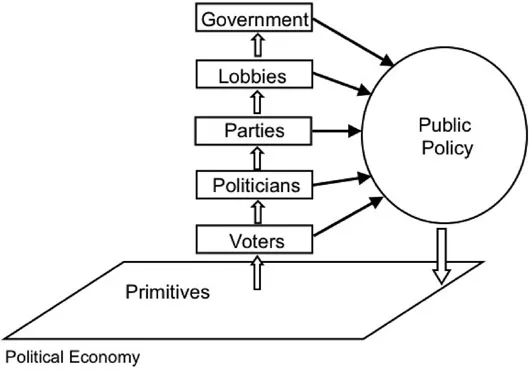

in this book is to bring closer together the great insights of politics and economics into the science of modern political economy, an ongoing process that began in the 1980s. Thus, in as much as we will consider Barack Obama and Donald Trump as democratically elected leaders affecting the most important policy and economic issues, we will also see them as individuals seeking to maximize their utility subject to constraints. Similarly, we will look at voters in much the same way that we would think about consumers deciding on what to buy, where to live, how much to save, and so forth. With this logic, we will be able to explain things like why and when people vote, what kinds of politicians end up running for office, when, why, and to what extent societies decide to redistribute wealth, and why some communities spend more than others to support their public schools. So, forget the notion that the ‘dismal science’ cannot explain politics. With the tools of modern economics, starting from basic primitives and assumptions about peoples’ preferences, we will explain political and economic choices. And by the end of this book, you will have taken your first steps as a fledgling political economist.

Figure 1.2 Overview: 1900–1980.

In Chapter 2, we will review some of the economics concepts that are necessary to follow along throughout the book. Chapter 3 then introduces the basic concepts of political economics which we will use as the building blocks to transition from the study of an economy to that of a political economy. Voters, electoral candidates, parties, lobbies, politicians and their career choices are the focus of the next five chapters, respectively. In Chapter 9, we will then fully integrate everything we have learned in the previous chapters and begin to analyze the political economy of specific policy issues, starting with public goods. Public schools, higher education, redistribution, health care, and immigration round up the rest of the chapters.

Figure 1.3 Overview: 1980–Present.

In the news

If you would like to familiarize yourself with the topic and the author of this book before plunging right into the reading, I suggest you watch the Pareto lecture I gave at the Collegio Carlo Alberto in June 2014, “The Devil Is in the Detail” available here: http://vimeo.com/110141762.

![]()

2

Basic tools of microeconomics

If we are to apply the tools of microeconomics to problems in political economy, we will first need to ensure that we have a common language. In this chapter, we will review some important definitions and methods that are commonly used in economics and will be needed for the rest of the book.

The most basic categories of objects in models of political economy are primitives and outcomes. Primitives, also known as exogenous objects to economists, can be thought of as the starting point, or fundamental building blocks of any model—when thinking about exogenous objects, remember that the prefix ex means “outside of,” or in other words something that exists outside of our model. In the natural sciences, primitives might take the form of physical constants or mathematical properties that we take for granted when building a model. They remain unchanged by the process being studied. A similar logic applies in economics: we will begin models by defining primitives, such as the people, preferences, and endowments that we take as given. The other fundamental elements, resting on the other end of the spectrum, are outcomes, also called endogenous objects—remember that the prefix en means “inside of,” or in other words something that e...