![]()

Chapter 1

Early beginnings

Even a brief history of play therapy needs to start with Sigmund Freud who famously documented the case of little Hans in the first published account in 1909 of the use of therapeutic play. Although he worked primarily with adults, Wilson et al. (1992) suggest that his observations on the meaning of children’s play were noteworthy for the contribution they made to later thinking, and in particular to that of his daughter Anna and her contemporary Melanie Klein. However, we need also to recognize the contribution of the Austrian psychoanalyst Hermine Hug-Hellmuth in the early 1900s, considered to be the first to work with children and provide them with play materials with which to express their internal world, thus conceptualizing play therapy – through play, children are able to communicate unconscious experiences, thoughts and feelings without the need for words or structured language.

Both Anna Freud and Klein, working from the 1920s onward, were considered pioneers in child psychotherapy, highlighting the relationship between children’s spontaneous play and free association used in adult psychoanalysis and recognizing that the cause of childhood psychiatric disorders was, in the main, unconscious conflicts which might be resolved when they were brought into the conscious by the therapist’s interpretations of the play and of dreams. There were differences to the approaches they developed, since Klein believed all play to be symbolic whereas Freud saw play as enabling the child to talk about their conscious fears, thoughts, anxieties and feelings while unconscious matter would be played out and that in doing so, the child was not necessarily playing symbolically but could be re-enacting real situations. Because Freud considered play enabled the child to verbalize in the manner of free association in adult psychoanalysis, she did not consider children under the age of seven suitable for therapy. However, she did see the need to create a strong relationship with the child in order to gain access to their inner world although this was in a more dependent way than the ‘neutral’ relationship we seek to establish today in non-directive play therapy (McMahon 1992).

Klein’s approach acknowledged the importance of the relationship between the mother figure and the infant and the idea that our inner world is constructed from our early mental processes. Because she saw nearly all play as symbolic, Klein relied heavily on interpretation and believed that the role of the therapist was to explore the child’s unconscious through reflection on the transference in the relationship the child made with the therapist. She also saw that the relationships children make in infancy impact on development although she saw development as occurring throughout the whole of life and as such contributed significantly to the field of developmental psychology. Despite the differences in their approaches almost resulting in a split during the 1940s within the British Psychoanalytical Society, Wilson et al. (1992) suggest that their contribution to the field of understanding and working with children has greatly influenced those who followed them, with the range of toys and resources used by Klein and the non-directive nature of her approach to the child’s play continuing to inform play therapy today.

Whilst Klein’s playroom was well resourced with a range of miniature figures, simple, non-mechanical toys, drawing and painting materials, paper, scissors, glue and water (Landreth 2002, McMahon 1992), sand play, a staple ingredient of play therapy today, was developed by Margaret Lowenfeld, a contemporary of Freud and Klein. Lowenfeld, a child psychiatrist, had recognized the importance of play to children’s development and understood that language was frequently an inappropriate medium for their expression of thoughts, feelings and experiences. She developed a non-verbal means of expression for children to use in therapy known as the ‘World Technique’ whereby children used a sand tray and miniature objects depicting all aspects of their lives to create small worlds to explore their own inner workings (lowenfeld.org no date). In addition to a large rectangular tray, water and pieces of plasticene were also available for children to construct landscapes for the vast range of miniatures she stored in drawers. Interestingly, rather than coming from a psychotherapy perspective, she noted that her greatest influence was H. G. Wells, and in particular a small book he had written describing the floor games his sons constructed using their toy soldiers and wooden blocks (Science Museum no date).

In the 1950s, Dora Kalff, a Swiss Jungian analyst worked with Lowenfeld and secured her agreement to develop her own style of working with sand which she called sandplay which also incorporated aspects of Eastern philosophy and Neuman’s system model. Sandplay is grounded in Jungian psychology and ‘helps honor and illuminate the client’s internal symbolic world, providing a place for its expression within a safe container’ (Friedman and Rogers Mitchell 2005). The approach emphasizes the importance of the therapeutic relationship in facilitating the client’s awareness in the present and analysis of the sandplay takes place after the session. This is in contrast to sandtray therapy, developed by Linda Homeyer and Daniel Sweeney, where the therapist is the facilitator and moves from a position of observation to reflection during the session. They describe their approach as:

Sandtray therapy also differs from sandplay in that it is cross-theoretical and thus considered to be more adaptable. However, both approaches serve to illustrate how differing theoretical perspectives lead to the development of new or alternative ways of thinking about both the process and practice of therapy and how client needs can inform and generate new theory.

Whilst some may suggest that we ‘stand on the shoulders of giants’, we need to accept that this position enables us to see ahead and to develop what has gone before in the light of our own experiences so that each and every one of us has the capacity to become a ‘giant’ and add to the development of both theory and practice.

A client centred non-directive approach

For child centred play therapists, it is the work of Carl Rogers and Virginia Axline which underpins the non-directive method of play therapy we currently employ. Rogers was an American psychologist in the 1940s, who was part of the growing humanistic psychology movement. From this approach, he considered a new style of working with clients, where the perception of the therapist as the ‘expert’ was replaced with the idea that the person themselves has an innate ‘actualizing tendency’ which drives them towards the achievement of their full potential.

This person centred approach recognizes that humans are biologically predetermined to seek contact with others as a means to survival and so our ability to make and sustain fruitful relationships, to know others and to be known by them is key to our physical and psychological well-being. However, it was Abraham Maslow, a contemporary of Rogers, who was the pioneer of the idea of human growth towards what he termed self-actualization, the idea ‘that our purpose in life is to go on with a process of development which starts out in early life but often gets blocked later’ (Rowan 2005).

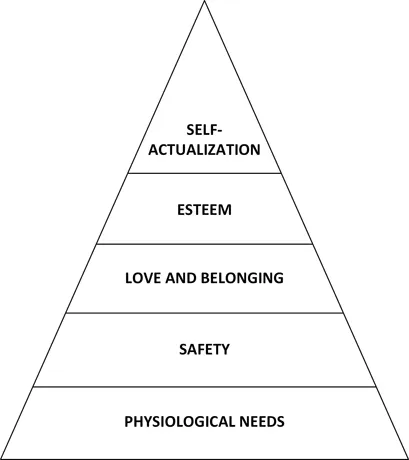

Rogers considered that for growth to occur we need to be open to experience, to trust and be trusted, to be curious about the world and have the capacity to be creative and compassionate. To create this healthy state, we require a safe and secure environment, one where we receive unconditional positive regard from another who is empathic and able to be their true self with us, to be congruent. The idea that there are certain conditions which are required for human growth and development echoes Maslow’s formulation of the idea that there are levels of need we must satisfy or meet before we can grow and ultimately self-actualize (see fig 1:1). The first four levels of the pyramid can be described as deficiency needs and are comprised of our basic physical and psychological needs which must be adequately met before we can meet our self-fulfilment need and achieve our potential (1943).

One of the key aspects of a person centred approach is that it does not rely on specific techniques but on the non-judgemental relationship established between the therapist and the client that is the therapeutic alliance. This in turn relies on the personal qualities of the therapist and their ability to stay with the client in a congruent manner which allows for that relationship to grow and develop in an atmosphere of trust and empathy. This in turn suggests a much more equal and democratic relationship than in the earlier psychoanalytic approaches and one predicated on the notion that rather than the client being in the hands of the therapist, they know what they have to do to ‘heal’ themselves and are in an environment where the conditions for this healing and subsequent growth allow for a greater degree of autonomy.

Although Rogers’ approach was initially used within counselling and psychotherapy, it was extended into education where it became known as student centred learning and was further developed in group situations such as large commercial organizations. In this way, it might be regarded as a forerunner of today’s coaching movement which also emphasizes the individual’s learning, development and growth potential as a way of stimulating critical thinking and new ways of being, supported by the relationship with the coach within a non-judgemental environment. (United States Department of Agriculture no date). Although the names Rogers and Maslow are those that spring to mind when we think about personal growth and self-actualization, the UK Association for Humanistic Psychology Practitioners (UKAHPP) reminds us that this is a rather reductionist view and that there were other key people in the human psychology movement at the time including Fritz Perls, founder of Gestalt therapy, Alvin Mahrer, who developed existential psychotherapy, Rollo May, who focused more on the tragic dimensions of life, and Jacob Moreno, who conceived and developed the idea of psychodrama as a means to facilitating insight and personal growth.

Another contemporary of Rogers and Maslow was Clark Moustakas who worked as a play therapist, and published Children in Play Therapy in which he also emphasizes the importance of the relationship:

He goes on to note that play therapy may be thought of as a set of attitudes which can be transmitted from one person to another and may be learned, although not taught. These attitudes – faith, acceptance and respect – are not imparted through any clear-cut formula, but reflect the therapist’s own life experiences and so are blended imperceptibly into the relationship. Some forty years later, I found myself echoing Moustakas’ thoughts in my own book, Play Therapy in the Outdoors:

Virginia Axline’s non-directive play therapy approach was heavily influenced by Rogers’ person centred approach and the core conditions of authenticity, non-possessive warmth and accurate empathy (Wilson et al. 1992) and her eight underpinning principles, reflective of Moustakas’ ‘attitudes’, still guide the work of non-directive play therapists today.

Axline’s eight basic principles of non-directive play therapy (1969)

The therapist must develop a warm, friendly relationship with the child, in which good rapport is established as soon as possible.

The therapist accepts the child exactly as he is.

The therapist establishes a feeling of permissiveness in the relationship so that the child feels free to express his feelings completely.

The therapist is alert to recognize the feelings the child is expressing and reflects those feelings back to him in such a manner that he gains insight into his behaviour.

The therapist maintains a deep respect for the child’s ability to solve his own problems if given an opportunity to do so. The responsibility to make choices and institute change is the child’s.

The therapist does not attempt to direct the child’s actions or conversations in any manner. The child leads the way; the therapist follows.

The therapist does not attempt to hurry the therapy along. It is a gradual process and is recognized as such by the therapist.

The therapist establishes only those limitations that are necessary to anchor the therapy to the world of reality and to make the child aware of his responsibility in the relationship.

Whilst Play Therapy is crucial reading for any therapist, Axline’s seminal book Dibs in Search of Self is an inspiring and moving account of her work with a particular small boy whose behaviour baffled the professionals around him to such an extent that they were left unsure of whether he was ‘mentally retarded’, autistic or gifted.