![]()

1

Objects of Knowledge, Subjects of Consumption

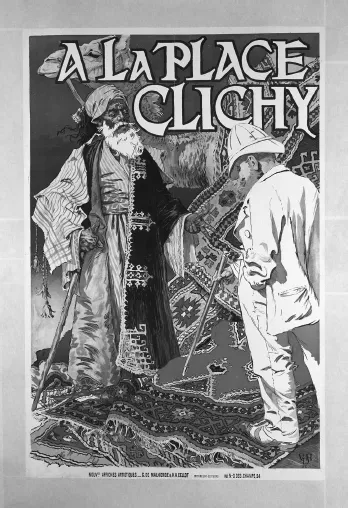

Figure 1.1 “A La Place Clichy”

“Hand-woven carpets are, in a sense, the eyesights of thousands of enamored of art thus we step on the eyesight of those in love with it.”

Kazem Shafaghi, “The Carpet Legend Is A Splendid One,” in Tehran Times, August 13, 1996, P. 9.

Connoisseur books, as a genre of knowledge production, have been crucial sites for the formation and transformation of material culture and for the production of racial and gendered differences, especially in the modern structure of empire. The genre has led to the creation of a decontextualized knowledge in which commodities like the Persian carpet are disconnected from the circuits of labor and complex hybrid trajectories of cultural meaning. Connoisseur discourses mediated and mediatized Oriental carpets in general and the Persian carpet in particular through the circulation of the carpet as a commodity via photography, advertisements, museum exhibitions, and books. This connoisseur knowledge was supplemented by an intertextual discourse1 found in journalism and travel writing, both anthropological and feminist, regarding the working conditions and pain that carpet weavers experienced. However, this discourse, which was both constitutive of and constituted by gendered subject positions, mostly served the moral economy of consumerism by uniting pain and pleasure in the commodity in order to influence consumer affect and desires. The transnational circulation of the commodity relied on the discourse of difference in order to produce both subjects of production and consumption. The connoisseur text’s interweaving of the tribal female carpet weaver’s labor with the sensory and exotic appeal of Orientalia transformed the carpet into a sublime and mobile object.2

In this chapter, I map out the commodification of Oriental carpets in the context of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries through connoisseur discourses. These texts circulated an aesthetic education through visual and textual representation, allowing consumers to evaluate and judge the valued from the non-valued. This form of education prepares subjects of consumption with the affect and civilizational optic of empire. This process of mediatization produced the Oriental and Persian carpet as a highly mobile object of desire that attached social subjects to particular notions of time and space, regardless of their location or dislocation within the territorial boundaries of the nation or the empire. The world of carpets and connoisseur literature provides a useful lens with which to examine the significance of knowledge production for the transnational circulation of commodities and the importance of the politics of mediation in the global marketplace.

Persian Carpets and the Gendered Politics of Transnational Knowledge

Originally a luxury item in the Safavid courts of the sixteenth century, the Persian carpet has now joined the assemblage of modern commodities. The importing boom for Oriental carpets began in the late nineteenth century,3 just around the time when a systematic form of knowledge of these carpets emerged. This knowledge industry, located mainly in France, England, and Germany, brought together academic and nonacademic writing (travelogues, trade guidelines, collectors’ books, and exhibition catalogues) in producing the connoisseur book—a particular genre of publication that offered a lush combination of words, pictures, and plates on the exotic appeal of the Persian carpet. This space for cultural and aesthetic knowledge was filled by a vast group of white male specialists, traders, and experts who created the profession of specialized research about the carpet. Oriental and Persian carpets and connoisseur books are a powerful example of how desire and demand for commodity production are created through the politics of value and the politics of knowledge.

Connoisseur books are an important site of the “visualization of knowledge,”4 which relies on both Eurocentric and masculinist epistemic assumptions.5 Indeed, as Barbara Stafford argues, this process of opticalization and visualization remains invested in logocentrism and the devaluation of sensory, affective, and kinetic forms of communication.6 The sheer quantity of connoisseur discourses has, over the years, created an “empire of merchandise.”7 These mediated discourses, originating in print and now carried into newer virtual formats, have enabled the complicity of the nation and empire in the context of a free-market economy and aided the expansion of consumer capitalism beyond the territorial boundaries of nation-states.

Based on my examination of over three hundred books, travelogues, and museum and trade catalogues in English and French (including a number of works translated from German to either French or English and from French or English into Farsi), I elaborate on the convergence of empire and nation in creating pedagogic and affective relations to material objects that are meant to exhibit total mastery of the Other’s culture. Focusing on late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century connoisseur texts, I present a genealogy of the carpet in a Foucauldian sense—an evolution of the carpet as a commodity constructed and circulated by these specialized texts.

Connoisseur discourses on the Oriental carpet engage in what Edward Said calls “citationary,” nature of Orientalism, referring to a large and varied body of writing that functions by referring repeatedly to itself.8 Here, I examine not only the constitution of connoisseur expertise but also the technologies within which such expert knowledge could examine, judge, and compare the carpet within the larger frame of knowledge and commodity production. These systems and technologies of organization of the carpet have created a transnational expert knowledge base that links image, information, and experience. This mediation relies extensively on transnational politics of gender and the fetishization of the Other. An examination of the relationship between knowledge and power is crucial for both our understanding of the production of desire for an object as well as the context within which a commodity is produced and exchanged. Questions of exploitation and the feminization of labor are an integral part of the apparatus of politics of knowledge. In the section that follows, I trace the shaping of colonial knowledge production and aesthetic education about the Persian carpet as a decontextualized cosmopolitan commodity.

Commercial Imperialism and Material Culture

While the study of the modern operation of empire through territorial and political claims to power has been central to a critical postcolonial perspective, the story of “informal imperialism,”9 which includes the complicity of the nation and the empire in entertainment, consumerism, and the military-industrial complex, still needs to be told. This imperialism is mostly established by peaceful means through networks of free trade, consumerism, and economic integration, as well as modes of knowledge production. For example, as Carol Bier argues, the modern production of the Persian carpet cannot be separated from attempts by colonial powers to maintain their dominance in Iran:

The commercial rivalry between England and Russia grew particularly strong, each evolving a political sphere of influence in Iran. In spite of the complaints of Iranian merchants, European imports reached a peak in Iran in the middle of the nineteenth century. But the decline of textile manufacturing in Iran was difficult to reverse. The most effective effort, however, was that attempted by foreign capitalists who sought to commercialize rug weaving to suit the new demands of the European market. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, investment and capitalization of local and foreign firms in Iran instigated development of the Persian carpet industry. Income from the sale of carpets supplanted that once derived from the export of silk.10

The history of commodities is linked to particular temporal and spatial formations and specific modes of economic exchange. Literacy and numeracy11 have been crucial both in investing value in certain objects as commodities and in making them visible in a regime of calculation, as they are circulated through old and new media and communication technologies. The study of material culture calls for what Van Beek terms “a recognition of materiality in social process, by systematically treating materiality as a quality of relationships rather than things.”12 Connoisseur books are noteworthy for the ways in which they construct the materiality of human interaction and the object in terms of the aesthetic and in terms of “the material process of mediation of knowledge through the senses.”13 In the connoisseur books, the visualization of knowledge is crucial to the life of the commodity. This process of visual literacy includes the optical instruction of the reader’s sight or vision, which is formed, educated, and trained to see in particular ways through the mediation of the expert. This process has been influenced by the discourse of commodity as a historical object, of civilizational and cultural difference, and of Orientalism. According to Edward Said, Orientalism is “a mode of discourse with supporting institutions, vocabulary, scholarship, doctrines, even colonial bureaucracies and colonial styles,” dominating, ruling over, and authorizing views of the Orient.14 The Orient for Said is “the place of Europe’s greatest, richest and oldest colonies.”15

As I have argued in the Introduction, the scopic economy is mediated through the creation of regimes of curiosity as well as modes of surveillance, producing both attachment to and detachment from the object being looked at. Indeed, the scopic economy functions as a modus operandi that constitutes social practices related to the production, exchange, and consumption of commodities. Here, I show how connoisseurs’ texts, academic writing, and advertisements, among other items, mediate the politics of value. The concept of scopic economy is crucial for tracing those regimes of visibility that enabled the construction of a commercial empire and the creation of transnational, imperial, and national networks; it brings to the fore the historic traffic between Europe, the United States, and the so-called Orient through the juxtaposition of taste, desire, consumerism, and commodity fetishism.

Connoisseurs, Curiosity, and Culture

I now turn to the regimes of curiosity that produce knowledge by participating in the consumption, circulation, and production of certain narratives, images, signs, tropes, and signifiers. These regimes do not define knowledge either by itself or in opposition to ignorance but, in Latour’s words, participate in “a whole cycle of accumulation: how to bring things back to a place for someone to see it for the first time so that others might be sent again to bring other things back. How to be familiar with things, people and events, which are di...