eBook - ePub

Vanishing for the vote

Suffrage, citizenship and the battle for the census

This is a test

- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Investigates the boycott of the 1911 census by Suffragettes

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Vanishing for the vote by Jill Liddington in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Irish History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Prelude: people and their politics

1

Charlotte Despard and John Burns, the Colossus of Battersea

It was a confrontation waiting to happen. Both shared a crimson socialist past and an impoverished south-London neighbourhood. Yet amid volatile Edwardian politics, what distinguished the two drove them apart into increasingly warring camps. Charlotte Despard, well-to-do eccentric widow, had chosen to leave her spacious home in the Surrey heathlands. She re-located to Battersea, selecting not just to any part of the borough, but the cramped noisy streets of Nine Elms. Here, down by the Thames wharves, shunting-yards jostled for space with gas works and pumping stations. By contrast, Battersea chose John Burns. One of eighteen children, he grew up competing for limited space in a cellar-dwelling near Charlotte Despard’s newly adopted home.

Both also shared a similar passionate late-Victorian Marxist socialism, well before the founding of the Labour Party; both immersed themselves idealistically in local practical politics of bringing urgently needed housing reform to Battersea. And both shared a deep belief in the right to vote, in the power of the ballot box, Burns even becoming MP for Battersea. All adults should be enfranchised – to help curb such cruel social inequalities.

But there the similarities ended. Their political priorities diverged dramatically, especially from 1906. Charlotte Despard, one-time socialist, shifted whole-heartedly to women’s suffrage – and never looked back. Meanwhile, John Burns became the first working-class man to enter the Cabinet. Thereafter, their political antagonism sharpened bitterly – democracy by equal citizenship, or democracy for welfare reforms; achieving desired aims using civil disobedience tactics, or by working lawfully through the parliamentary processes.

Burns was not only the sole Cabinet minister with impeccably proletarian credentials; he alone also had the misfortune to represent a central London constituency, almost visible from suffrage headquarters. And Charlotte Despard, rising through the suffragette ranks to become Women’s Freedom League (WFL) president, soon had her sights trained on the Member for Battersea. Burns, preoccupied with pushing reforms through his ministry, swatted off such irritating hecklers as so many small buzzing flies. Yet neither WFL nor WSPU suffragettes let opportunity slip to harass Burns. As the Liberal government’s battle with the House of Lords grew fiercer, and with it the likelihood of elections, the more personal became the mortal combat between Despard’s suffragettes and Burns’s Battersea loyalists.

*

Their two back-stories could not contrast more dramatically. Charlotte French was born in 1844 into a well-connected naval family. This however offered scant protection either from a mid-Victorian ramblingly inadequate education, or from family misfortune: her father died when she was ten, and her mother was committed to a lunatic asylum shortly after. Still rather unworldly, Charlotte in 1870 married Maximilian Despard. A successful businessman and a rationalist, Max allowed his bride new freedoms. But it was, her biographer suggests, a chilly liberty; and for Charlotte it proved a disappointing marriage, not least because it remained childless.1

The prosperous Despards moved into an imposing mansion standing in fifteen acres of tranquil Surrey heathland at Oxshott. Since the opening of the Waterloo–Guildford rail line in the 1880s, their village had become a desirable retreat for well-to-do Londoners. Here, Charlotte wrote, ‘I soothed my disappointment and expended my superfluous energies in taking up all sorts of causes’ – of which particularly significant was the Nine Elms Flower Mission whereby ladies with country gardens distributed flowers in London slums. For her, this spelled Thames-side Battersea.

Max died in 1890. Charlotte became something of a recluse, shutting herself up at home. It was an aristocratic Oxshott neighbour who came to her rescue. Hearing of the widow’s grieving seclusion, she suggested taking up her Battersea philanthropy again. Charlotte seized on this with uncompromising vigour – and her own life now began. ‘It was only after my husband’s death’, she said, ‘that I was able to give full expression to my ideals.’2

She was soon unstoppable. Within months, she had bought a house on Wandsworth Road near Nine Elms. This morphed into the Despard Club, a nurse was hired, toys provided for needy back-street children, and trips organized out to Oxshott. Indeed, Charlotte’s brother John French, already Lieutenant-Colonel, moved his family into Max’s mansion. So, although she retained a small cottage on the estate, Charlotte severed her last link to married life and went to live in Battersea.

Meanwhile, she remedied her woefully deficient schooling, reading American idealist writers Thoreau and Whitman. She became a vegetarian, discarded her oppressive corsets, took to wearing sandals and adopted what became her distinctive hallmark headdress, a black mantilla. Yet Charlotte went further: she bought a house in the heart of Nine Elms: 2 Currie Street. Here she opened a surgery for local children, then in 1895 buying premises round the corner in Everett Street for a second Despard Club. She also plunged into local political life, making her first speech (brother John loyally accompanying her), and stood successfully for election as Poor Law Guardian. This was the start of Charlotte’s long public career, pursuing unscrupulous slum-landlords and mean-minded workhouse masters. ‘The Poor Law’, she recalled later, ‘was my apprenticeship’.3

2 Charlotte Despard, WSPU, 1906–7.

Witnessing the brutalizing effects of unemployment so close to hand, it was but a small step to her conversion to socialism. This became Charlotte’s new religion: the Despard Club was renamed Socialist Hall. But some socialists’ suspicion of ‘women’, plus sectarian squabbling in the Marxist Social Democratic Federation (SDF), left her disillusioned. She shifted her allegiance towards Keir Hardie’s new Independent Labour Party (ILP), with its idealistic yet practical socialism. She became friends with trade union organizer Margaret Bondfield, who recalled staying at Charlotte’s Oxshott cottage; it was an ‘open house for tired people’ and, seeing her idiosyncratic hostess ‘on her knees, weeding her garden at sunrise, she seemed to me like saint at prayer’.4

Through such labour networks, Charlotte became an adult suffragist – wanting the vote for all adults, rather than just for those women who satisfied the property qualification. Indeed, after the Liberals’ landslide victory at the January 1906 General Election, Charlotte joined a suffragist deputation in May to the new Prime Minister, Campbell-Bannerman. She went as an adultist; and was, one suffrage pioneer wrote later, ‘unspeakably rough and rude to me – on the sole ground that I supported what she pleased to call the “limited” bill instead of working for “adult suffrage” … She then regarded us of the WSPU as narrow-minded foolish people’.5

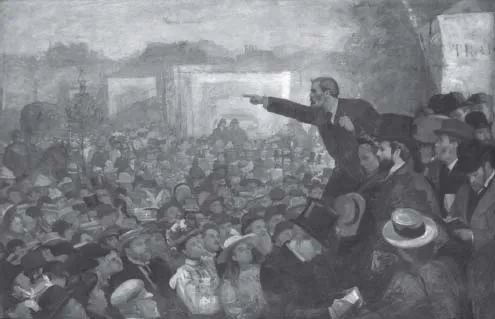

3 John Burns MP, addressing an open-air meeting, 1897.

However Charlotte, never one to entertain half-hearted doubt when an idealistic certainty could be grasped, soon radically shifted her stance. Within months, she had transferred her allegiance to Emmeline Pankhurst’s recently formed WSPU: ‘I had found comradeship of some sort with men … [but] I had not found what I met on the threshold of this young, vigorous union of hearts’.6 What helped change her mind? Probably Keir Hardie’s own women’s suffrage commitment and, through her local Guardian experience, what she saw of John Burns and his Tammany Hall electoral domination of Battersea – from which women were excluded.

John Burns was born in 1858 in Vauxhall, south London, into just such over-crowded slum housing that Charlotte had selected as her mission to redeem. The sixteenth of eighteen children only nine of whom survived infancy, John was aged about nine when the family moved into a basement dwelling in nearby Battersea. His mother worked exhaustingly taking in laundry; his father, never a steady provider, was unable to afford the weekly penny to keep John at school, so he had to leave when he was ten or eleven. In 1870, he began working in a Battersea candle factory, later training as a riveter, then obtaining an engineering apprenticeship on the north bank of the Thames. Eating his lunchtime ‘piece’ here, he could have an eye along the river to Westminster.7

Energetic and ambitious, Burns soon left his family behind. He became a voracious reader – Tom Paine, Owen, Ruskin; and was inspired by an exiled French communard from whom he learnt ‘Le pouvoir politique est indispensable … It faut voter.’ Convinced of the absolute necessity of the ballot box, and now in the engineers’ union, Burns joined the SDF. Here his powerful oratory won many converts. His voice was likened to a giant gramophone, his earthy epigrams springing straight from his own London streets. Burns was twice arrested over free speech, but just about found time to get married.8

The sectarian SDF straitjacket could not however restrain Burns long. To advance urgently needed reforms for the people of Battersea, he was elected in 1889 onto the newly formed London County Council (LCC). Here he distinguished himself with his keenly practical engineer’s craft skills – bridge-building, efficient drainage systems; he even attended LCC debates armed with chunks of mortar, all to further the interests of working-class families. After the great London dock strike, Burns became the towering labour figure. Everyone wanted his golden voice on their side. Even the Battersea Liberals eyed him as a potential candidate. Indeed, in 1892 he was elected as local MP, his salary provided by the Battersea Labour League; and the family moved up to a healthier neighbourhood, Lavender Hill.9

Burns trod a fine line between his original labour convictions and growing Liberal loyalty. A metropolitan secularist, he found all the ILP ‘religion of socialism’ irksome. Indeed, after MPs like Keir Hardie joined with trade unionists in 1900 to form the Labour Party, Burns found himself increasingly out-of-step. A tub-thumper, he still maintained a good line in vilifying opponents as ‘the riff-raffof the Stock Exchange and the parliamentary dead-beats’. However, his impeccable proletarian credentials and powerful oratory made him an increasingly desirable ally for the radical wing of the ascendant Liberal Party.

So when Campbell-Bannerman formed his Liberal government in late 1905, confirmed at the January 1906 Election, it was no surprise that Burns was appointed to the Cabinet, its first working-class member. Appointed President of the Local Government Board (LGB), Burns might be vilified as a class traitor by middle-class Fabian reformers like Beatrice Webb; he might be over-shadowed by the instinctively brilliant David Lloyd George, now President of the Board of Trade; he might even be joshed for walking down Lavender Hill resplendent in court dress with gold lace. Yet he remained wildly popular in his own Battersea patch. At his first local appearance as minister, Burns, accompanied by his wife and son, was received with tremendous cheers, and then spoke for nearly two hours. Burns knew that real power lay within grasp: by working hard, he could now do things, make real improvements to real people’s lives.10

So what were his political priorities? He continued to support adult suffrage, including it in his election address. Indeed, for Saturday 19 May 1906 Burns wrote in his diary of the deputation Charlotte Despard had joined:

Up at 5. Surveyors’ gathering at [Battersea] Town Hall, reception and speech. LGB in time to see Suffrage Deputation emerge from Foreign Office. Went offwell but disappointed with C[ampbell-]B[annerman]’s refusal to pledge Government.11

It seems Burns shared something of the women’s disappointment. He may ironically then have been more sympathetic to women’s suffrage than was Charlotte Despard, still an adultist. And since he must have known her, he would surely have recognized her eccentric profile?

Soon Burns had an opportunity to promote policy close to his heart. He presided over the first National Conference on Infant Mortality. His speech makes two points absolutely clear. First that, drawing on personal experience, Burns spoke with passion. A hundred thousa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of maps

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Chronology

- Introduction

- PART I Prelude: people and their politics

- PART II Narrative: October 1909 to April 1911

- PART III Census night: places and spaces

- PART IV The census and beyond

- Gazetteer of campaigners

- Notes

- Select bibliography

- Index