![]()

1

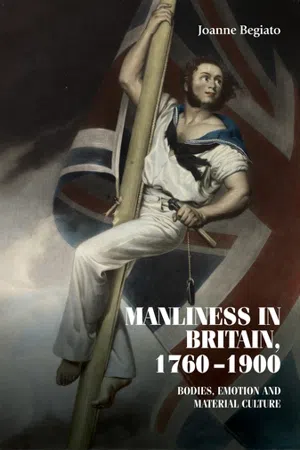

Figures, faces, and desire: male bodies and manliness

Introduction

Manliness was conveyed through beautiful, virile, male bodies; men’s muscles, hair, stance, movement, and facial features delineated, even rhapsodised, in print, visual, and material culture.1 Such appealing male figures and faces were associated with positive emotions that were coded as both manly and moral.2 This chapter explores their changing forms over time, but also addresses the question raised by such bodies. Intended to promulgate and disseminate exemplary masculinity, what purpose did their beauty serve? Scholarship that explores attractive, eroticised male bodies often considers them as unusual or transgressive, either because they are found in erotic or pornographic works, or because they are considered to primarily appeal to a homoerotic viewer.3 Depictions of a ‘normative’ male body are also deemed problematic within the framework of the gendered gaze, which positions the male viewer as active and dominant and the object of his gaze as female and subordinate.4 Henk de Smaele, for instance, argues that Richard Westmacott’s monument to the Duke of Wellington (unveiled in 1822) failed in its attempt to deploy the naked idealised male body to contribute to hegemonic ideals of masculine citizenship. This was because ‘turning the male body into an object of the gaze evokes the possibility of female and homosexual desire’, resulting in ‘disorder and confusion’ rather than the virtuous order the spectacular body was meant to achieve. While contemporary satire mocked women’s sexual interest in the statue, and it was later used in anti-government criticism, de Smaele’s reading of the image is selective and certainly does not bear the weight of his conclusion that ‘masculine power rests on the absence of a fixed embodied standard against which one can be measured’.5

In contrast, and to answer the question of the role of male beauty in disseminating ideals of manliness, this chapter takes a queer approach which deliberately makes strange the conjunction between physical beauty and masculine values. It adopts the techniques of scholarship that queers sexual constructions and rejects assumptions about normative masculinities and how they were created and circulated.6 Thus, it recognises the desirability of idealised male bodies and makes this the foremost object of scrutiny.7 Overall, it proposes that beautiful male forms and appearances were intended to arouse desire for the gender that these bodies bore, whilst also, no doubt, stimulating erotic feelings in some of their male and female viewers. This nuances our understanding of the gaze. It shows that the idealised manly body was active, since it was an agent of prized gender values. Yet it was also passive, as the object of a female and male desirous gaze, and subordinate, for although some of the descriptions of idealised male bodies in this chapter were elite, as it and later chapters show, many manly and unmanly bodies were those of white working-class men.8 Due to the sources used, it is white bodies that are the focus here, but it is acknowledged throughout that in the imperial context of the long nineteenth century, the idealised manly body was also racialised, with whiteness constructed through accounts of ethnic and racial ‘others’.9 Throughout, manliness was measured through bodies and the emotions they symbolised and aroused.10

Viewing the manly form: poise, power, and pose

In art, and, later in film, idealised men’s bodies were often described in dynamic motion: fighting, wrestling, throwing, lifting, and working.11 Other bodies were caught at rest, between labours, or adopting a pugilistic, athletic, or muscular pose, all of which still gestured to a more active state. Attention to this movement exposes the plethora of ways in which the male body was viewed and evaluated by spectators, often to discipline and categorise it. Motion was a marker and privilege of mature manhood, for example, and a long-standing moralistic trope insisted that male youths work or exercise to distract them from sin. In 1750, for example, the Ordinary of Newgate explained that Anthony Byrne, who was convicted for breaking and entering, was put to apprentice once he had arrived ‘at a proper Age to undergo Fatigue, and to keep his robust and manly Faculties in Agitation, in order to shield him against the Sallies of Idleness, the Root of all Evil’.12 Anthony failed because he rejected active work. A century later, Samuel Smiles advised readers of his chapter on ‘Self-Culture’ that the only remedy for youths prone to ‘discontent, unhappiness, inaction’ was ‘abundant physical exercise, – action, work, and bodily occupation of any sort’.13 Under the shadow of race science in the later nineteenth century, as Elspeth Brown observes, ‘movement emerged as a key indicator of racial evolution’. Anthropometric photography in the 1880s was aligned with developments in physical anthropology to use human locomotion as an identifier of racial difference, with bodies of colour placed lowest on the hierarchical scale.14

Men’s moving bodies were also viewed for pleasure and entertainment. Pamela Gilbert shows that men participated in popular rural sports, including wrestling, fighting games, hurling stones, and bare-knuckle boxing, to make money, win prizes, and resolve disputes, but also ‘to affirm masculinity through the demonstration of strength, competitiveness, and the ability to endure pain stoically’.15 Pleasure in men’s moving bodies was clearly understood to be the draw for a paying audience and marketed thus in the press. Frank E. McNish, an American acrobat performing in London, was described in ‘Heroes of the Hour’ (1889), as possessing a ‘fine athletic frame – a remarkable combination of grace, agility, and strength’.16 The representation of men as bodies in motion, therefore, offers insights into the ways in which embodied manliness was consistently scrutinised although its form changed over time.17

The variation in men’s bodies, bodily styles, and form can be captured by three convenient, if somewhat simplified, terms: ‘poise’, ‘power’, and ‘pose’. These conform to a rough chronology, wherein the idealised manly form shifted from slender, graceful strength to more bulky, solid heft, to sculpted muscularity from the 1760s to 1900.18 Two very different definitions of exercise at 1755 and 1897 capture the changing nature of the goals of male exercise regimes, from moulding elite bodies to a more democratic commercialised physical culture. In his 1755 Dictionary of the English Language, Samuel Johnson defined exercise as ‘Habitual action by which the body is formed to gracefulness, air, and agility.’19 One hundred and fifty years later, Eugen Sandow’s regime of physical exercise targeted specific muscles to bulk them up, accompanied by a table enabling the user to record ‘before’ and ‘after’ measurements.20 Sandow headed a physical culture iconography in which the male pose was a signifier of fitness to which men from a variety of social classes could aspire.21 The following section offers a broad-brush chronological model of these bodily types to demonstrate how they stimulated desire for the manliness they embodied.

First, though, it must be noted that poise, power, and pose were not successive, distinct bodily categories since they shared several qualities.22 Most obvious is that the classical body influenced by Greek antique sculptures was at the core of all formulations of male physical beauty and health.23 Two classical male body types were especially potent: the young, slim athleticism of the Ephebes and the mature, hefty, heroic Herculean form; the first clean-shaven, the other bearded.24 In ‘The Marquis and the Maiden’ (1857), for example, the stalwart heroic groom was described as ‘faultless in his form and build, a young Apollo, with that careless ease of manner, and with a certain bold frankness of air’.25 Martin Myrone’s study of masculinities in British art suggests that Georgian ideals of manly beauty focused upon the less brawny Greek model, while the mature Herculean body type came to symbolise the muscular Christianity dominating the second half of the nineteenth century.26 Roberta Park’s assertion that until 1850 idealised men were represented either as ‘lithe and slim’ or ‘ponderous’ pugilists is, however, somewhat simplistic.27 After all, the art that resulted from using boxers as life models in...