![]()

1

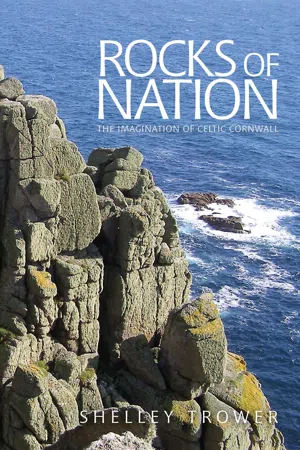

Primitive rocks: Humphry Davy, Cornwall’s Geological Society and sublime mineral landscapes

The newly established Geological Society of London, formed in 1807, set out as a primary purpose its ambition to produce a geological map of Britain. The editors of the first issue of the Society’s journal, Transactions of the Geological Society (1811), stated their hope that its members will continue to donate mineral specimens that will lay the foundations of such a map.1 A few years later, in 1814, a similar society was formed in Cornwall, which then produced its own journal, Transactions of the Royal Geological Society of Cornwall (1818), the first issue of which echoed the London version of Transactions, though on a smaller scale: ‘In the construction of a geological map of Cornwall, the Society has made considerable progress, and the Council trust that from the zealous and united exertion of its members, its completion may be confidently anticipated’.2 At this point the president of the London Society, George Bellas Greenough, was about to publish his Geological Map of England and Wales, the result of a cooperative collaboration between the society’s members who sent in rock specimens from various localities throughout much of Britain.

What such maps clearly highlighted were regional differences in geology, differences which formed a basis for understanding how particular regions were not only composed of certain kinds of rocks but also exhibited other properties. Of much interest, at least initially, was that some regions contained large quantities of metals and other valuable resources suitable for mining. Thus the first geological map of England ever to be produced, in 1815, was by William Smith, whose work as a land surveyor (landowners’ incomes depended on the exploitation of natural resources) provided him with the necessary experience in observing the geology of a wide range of areas across England and Wales.3 Greenough then drew extensively on Smith’s map for his more collaborative Geological Map, and London’s Transactions refer to the practical uses of such a map, but it was Cornwall’s version of the journal that most heavily emphasised, from the outset, the purpose of the society and its prospective map as being to serve mining interests: to contribute ‘to the advancement of the mining resources of the County of Cornwall’ as well as ‘to the progress of geological knowledge’.4 But while rock-mapping had a clear economic function, it was also motivated by a flowering interest in travel and landscape aesthetics, and it is these curiously distinct yet overlapping interests in mining and landscape that this chapter will consider in combination.5

In different ways the interests in both mining and landscapes produced an intensified focus on ‘primitive’ rocks, such as granite – rocks found mostly in northern and western regions of Britain – largely because these rocks both contain some of the most valuable mining materials6 and underpin some of the most dramatic, sublime mountainous landscapes. Focusing on the ‘primitive’ region of Cornwall, this chapter will explore how members of its Geological Society, including the ‘Romantic scientist’ Humphry Davy,7 mapped out geological regions as distinctive in the early nineteenth century. Davy observed these regional qualities in his poetry and his scientific writing, and contributed to claims of local distinctiveness and expertise, which developed in opposition to a growing professionalism centred in London. This chapter will, in other words, consider how scientific and poetic descriptions of the mineral value and the aesthetic qualities of landscapes support the claims of Cornwall’s Geological Society to regional difference and expertise.

With their interests in mining as well as landscape aesthetics, Davy and the Cornish geologists provide a different angle from the more usual focus on the aesthetic interests of the canonical Romantic poets (of whom Wordsworth is representative in this chapter) and of travel writers, who typically engaged only minimally with industrial concerns. Through its focus on the case of Cornwall, this chapter can contribute to the strand of Romantic studies that has continued to develop a critique of the canonical, unified “centre” of English poets by establishing a devolved plurality of Romanticisms, registering the complexities of national and regional contexts across the British Isles.8 Since the 1980s critics have considered the complexities of Scottish, Irish, and Welsh Romanticisms and have turned attention more recently to ‘the provincial diversity of English Romantic writing’, as Nicholas Roe puts it.9 By turning to the West Country, Roe relocates the roots of English Romanticism, focusing on a region that offers a convincing alternative to the Lake District. Roe’s collection, however, has little to say about Cornwall,10 a county that is of particular interest here as it is part of England but also began to develop a distinct regional or even national identity. By taking Cornwall as its focus, this chapter will identify how a regionally based version of Romantic science stakes out a specific territorial claim, which is grounded in both the aesthetics and the mineral value of primitive rocks. Cornwall’s geologists emphasise the distinctiveness of Cornwall through its ancient, sublime rocks and its exceptionally valuable minerals, in other words, over which they stake out claims of expertise and ownership. They present an alternative version of Romantic geology that engages with the economic conditions in which a proto-nationalism begins to emerge.

Primitive rocks and the sublime

Historians of geology frequently observe that the study of rocks and fossils began to open up a new perspective of earth history in the late eighteenth century. The emerging discipline of geology showed that the history of the earth extended back immeasurably, far beyond the appearance of humankind, and beyond what the Bible had accounted for.11 ‘Primitive’ rocks were usually considered the oldest, containing no fossils and thus appearing to pre-date the existence of all living beings. Historians and critics have mostly focused, however, on the role of sedimentary rocks and the fossils found in them, which, by providing evidence of the existence of species that over millions of years had become extinct, were so crucial to the establishment of theories of evolution.12 Fossils also became important to the process of mapping out rocks in terms of their age, a taxonomic enterprise known as ‘stratigraphy’, which was a core driver of nineteenth-century geology.13 But in the early decades of the century geologists largely ignored fossils, which is evident in the first few volumes of Transactions, which placed by far the most emphasis on minerals and rocks. As Simon Knell points out, for example, only one of the eighteen articles in the first volume of London’s Transactions concerns fossils.14 In the first volume of Cornwall’s issue there are none, while over half of the articles discuss granite, at that time considered the first among the primary rocks since it so often seemed to underlie all other primary rock masses.15

There was much debate between the theory proposed by Abraham Gottlob Werner, that granite was the first of all rocks to form in the primordial sea, and the theory proposed by James Hutton, which understood it to have an ‘igneous’ origin, to be formed by the earth’s internal heat, for example through volcanic action. According to Hutton’s theory, which gained increasing ground in the nineteenth century, granite could erupt or ‘intrude’ into previously formed sedimentary rocks, and was not therefore in all cases the most primitive formation. But at this stage granite was still widely thought to be the oldest of rocks, and geologists including Davy, as well as poets including Wordsworth and Goethe, used the aesthetics of sublimity in their descriptions of geological formations and landscapes – especially those formed of primitive rocks – which were thus apprehended as vast, potentially infinite and incomprehensibly ancient.16

Marjorie Hope Nicolson discusses how natural philosophers among others developed the concept of ‘geological time’ as indefinite in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which helped to generate the Romantics’ interest in mountains in general as sublime, while they were previously considered ugly disfigurations of nature, the result of God’s wrath.17 Poets including Wordsworth were also well acquainted with contemporary geological theories such as Werner’s, building on the sense of primitive rocks in particular as ancient or even eternal, and thus sublime.18 Wordsworth’s travel narratives contain many geological observations. His An Unpublished Tour (1811–12), for instance, describes his impressions when looking down into the depth of a chasm in the Lake District, cut through by a brook over ages, and contrasts the fragile slate rocks and earth, which are here on the verge of collapse against the sublimity of the ‘ever-lasting granite’ and ‘basaltic columns’ belonging to another scene: ‘Among sensations of sublimity, there is one class produced by images of duration, [or] impassiveness, by the sight of rocks of ever-lasting granite, or basaltic columns, a barrier upon which the furious winds or the devouring sea are without injury resisted.’19 This sense of sublimity is characteristic of Wordsworth’s wider treatment of the sublime as involving great temporal durability or even eternity along with great spatial depths or heights. In ‘The Prelude’ the ‘disappearing line’ of a road is perceived as extending into infinite space, or into eternity, across a hilly landscape with its rocky, ‘bare steep’:

a disappearing line

Seen daily afar off, on one bare steep

Beyond the limits which my feet had trod

Was like a guide into eternity,

At least to things unknown and without bound.

(Book 12, 148–52)20

Despite the usual focus on the sublime as a psychological category, we can identify a ‘natural sublime’ – to refer to sublime objects rather than subjective experiences of the sublime – considering its manifestations in scientific as well as aesthetic contexts. As Noah Heringman comments, ‘Outside aesthetic theory, the word “sublime” is generally used in eighteenth-century Britain to describe physical objects’ such as rocks and land forms, a usage that continues in the early nineteenth century.21 Employing this sense of the natural sublime, in his public lectures on geology delivered in 1805, Davy referred to granite as one of the commonest types of ‘primitive’ rock and described its landforms as having special qualities of sublimity both in its spatial ‘magnitude’ and, he implied, in its temporal continuity, its ability to survive, to endure, to withstand the waves. Like Wordsworth, with whom he exchanged ideas about poetry and science, Davy describes how granite is able to ‘resist’ the waves of the sea. It is found, he goes on to observe, at the ‘extremity of...