eBook - ePub

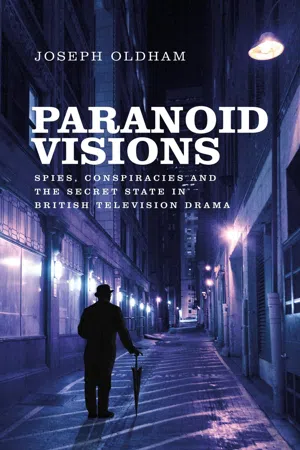

Paranoid visions

Spies, conspiracies and the secret state in British television drama

This is a test

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Paranoid visions explores the history of the spy and conspiracy genres on British television, from 1960s Cold War series through 1980s conspiracy dramas to contemporary 'war on terror' thrillers. It analyses classic dramas including Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, Edge of Darkness, A Very British Coup and Spooks. This book will be an invaluable resource for television scholars interested in a new perspective on the history of television drama and intelligence scholars seeking an analysis of the popular representation of espionage with a strong political focus, as well as fans of cult British television and general readers interested in British cultural history.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Paranoid visions by Joseph Oldham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

‘A balance of terror’: Callan (ITV, 1967–72) as an existential thriller for television

Introduction

The arrival of the spy genre on British television came initially in the form of a cycle of adventure series focused loosely on themes of international intrigue which occupied a prominent place in the schedules of the 1960s. For the most part, this strand was overwhelmingly associated with the commercial ITV as product of its popular appeal to the growing working-class viewership and embrace of a mass public beyond that of the more paternalistic BBC. Guided by trends on American television (which served as both a model and a crucial ancillary market) such series tended towards an up-beat and aspirational tone. Yet at the same time ITV’s engagement with the new mass public also instigated a tradition of ‘progressive realist’ drama associated in particular with the single play series Armchair Theatre (ITV, 1956–74). Seeking to provide a closer engagement with the realities of working-class life than had hitherto been provided by the BBC, this tradition contrasted strongly with the optimistic qualities of adventure series, instead focusing firmly on social problems and inequalities. Thus, although the introduction of ITV marked a key turning point for British television in terms of both genre programming and class representation, prior histories of British television drama have generally characterised these two sites of innovation as essentially unconnected.

This chapter, however, will trace how these two areas later converged into the cynical, anti-heroic spy series Callan (ITV, 1967–72). This reworked the existential spy thriller tradition associated with novelists such as John le Carré and Len Deighton into an ongoing television format, adopting their tone of institutional alienation and moral ambiguity in the face of the Cold War. As such, it was one of the first television spy series to extensively site its drama within the conspiratorial workings of the secret state, here used as an allegorical device to dramatise the class tensions of British society. On an aesthetic level, a style of studio-based recording derived from Armchair Theatre, in particular using mobile cameras and expressive close-ups, enabled the series to provide an unusually psychological focus for a spy drama of the period. Combined with the specifically televisual form of the ongoing series and early innovations in serialised storytelling, this allowed the existential subgenre to transcend its literary roots, with a growing audience becoming invested in the struggles of its titular protagonist as the cultural optimism of the 1960s gave way to the more anxious climate of the 1970s.

ITV, class and genre: Armchair Theatre and the adventure series

A foundational aim of ITV was to counter the perceived Londoncentric bias of the BBC, and as a result it was established with a regional structure, gradually rolled out from 1955 to 1962. Licences were issued by the regulatory Independent Television Authority (ITA) to 15 separate companies in order to run regional franchises and provide programming designed specifically for that locality. Yet with the prospect of producing their entire output independently proving a huge economic burden, the regional companies agreed to share programmes, forming what would transpire to be a more cohesive national network. The companies who were awarded the franchises for the most profitable metropolitan areas, Associated-Rediffusion, Associated Television (ATV), Associated British Corporation (ABC) and Granada Television, were able to establish an effective oligopoly on nationally networked programmes, particularly in costly areas such as drama production, becoming known as the network companies or ‘Big Four’.1

Although the continuing series had already been established as a form for popular drama when ITV commenced broadcasting, during this period the single play with an entirely self-contained narrative was widely considered to be the vehicle for television’s most prestigious dramatic production, connecting most directly with the cultural-enrichment ideals of public service culture. Of the ‘Big Four’, ABC, the franchise-holder for weekend broadcasting in the Midlands and the North, emerged at the forefront of such programming with its Armchair Theatre strand which, over the late 1950s, came to focus on original, contemporary drama and develop the first school of television writers, including Alun Owen, Clive Exton and Ray Rigby. Despite producing plays in many genres, Armchair Theatre became best known for providing television drama’s first substantial engagement with the concurrent New Wave (or ‘kitchen sink realism’) in British literature, theatre and film. Introducing a new focus on working-class life, John Caughie describes how the strand shook loose ‘the metropolitan, theatrical, and patrician codes which had defined the role of television drama in a public service system’.2

During this time most British television drama was still broadcast live from studios that had been specially constructed or converted for electronic transmission, and Caughie argues that this established ‘the assertion of immediacy, liveness and the direct transmission of live action as both an opportunity and an aesthetic virtue of the medium rather than as a mere technological constraint’.3 Even within the limitations of live broadcasting, Armchair Theatre was also aesthetically innovative, developing a ‘house style’ based on shooting in depth with highly mobile cameras and the use of highly expressive lighting, creating drama that was more dynamic and three-dimensional than concurrent BBC productions.4 These innovations placed ABC at the cutting-edge of original, contemporary television drama.

By the turn of the 1960s there was a growing interest in pre-recording such productions on Ampex videotape. This offered the obvious advantages of removing mistakes and creating greater flexibility with scheduling, whilst enabling television companies to retain the same studios and equipment as live television. More fundamentally, as Caughie writes, it brought to an end television’s ‘essential ephemerality, and transformed immediacy and liveness from technological necessities into residual aesthetic aims’.5 Yet videotape was lacking in versatility, with no process for physical editing invented until 1959, and even then this was strongly discouraged as it prevented the widely adopted practice of reusing the expensive tapes. As a result, the practice of as-if-live recording continued, retaining from live drama the multi-camera set-up, live vision mixing and largely studio-bound style. Thus the practice developed over the 1960s was to record largely in order in a stop/ start manner with only the most serious mistakes removed. Yet it also became increasingly common to provide an expanded canvas through the use of pre-filmed telecine inserts on 35mm film for location sequences, which would be played in during the main studio recording.

ABC’s drama output was, however, more diverse than its success with Armchair Theatre and the single play. In the early 1960s, responding to the popular re-emergence of the spy thriller, it developed The Avengers (ITV, 1961–69), a series which centred on the gentleman spy John Steed (Patrick MacNee) and his associates. This progressed through various styles of production; for some of its earliest episodes in 1961 it was broadcast live to only selected regions, and only later did it graduate to being a videotaped production networked to the entire country. When Catherine Gale (Honor Blackman) joined as Steed’s partner for the second series in 1962, The Avengers grew to become a popular national hit. During this phase it worked to overcome its production limitations through an increasing self-awareness in the scripts, which would often adopt outlandish and fantastical premises and parody the conventions of more conventional spy series and other genres. In 1965, with the arrival of Emma Peel (Diana Rigg) as replacement co-lead, ABC took advantage of The Avengers’ growing popularity and redeveloped it into a much more polished production based at Elstree Studios.

By this point Elstree, a long-standing production base for the British film industry, had become the home of a mini-industry of adventure series generally located in the vague terrain of international intrigue and espionage, including Danger Man (ITV, 1960–66), The Saint (ITV, 1962–69), Man of the World (ITV, 1962–63), and The Baron (ITV, 1965–66), building upon the international success of the James Bond film series beginning with Dr. No (Terence Young, 1962). The production of such programmes was dominated by the Incorporated Television Company (ITC), a fully-owned subsidiary company of ATV, the ITV franchise-holder for the Midlands weekday and London weekend services. ITC’s adventure series occupy an awkward place in British television history, sitting anomalously in accounts that otherwise typically emphasise progress through live broadcasting and videotaping. Instead, this was essentially a bubble in the British television industry that functioned more in accordance with American aesthetic and commercial practices.

Like American genre series such as Westerns and cop shows, these were glossy productions shot on expensive 35mm film and in studios designed for feature film production rather than live television. In contrast to the multi-camera shooting of live and videotaped drama, these series used the single-camera set-up that had been the default mode of feature film production since the 1910s, with one camera used to individually record all of the shots required for a different scene from all required angles, which were then assembled through post-production editing. This enabled more control over individual shots and a greater focus on exterior locations, elaborate action sequences and tight editing. However, it was a costly mode of production which could only be made economically viable through ITC’s entrepreneurial pursuit of international sales, particularly to the American networks. In adapting The Avengers to this model, ABC therefore also targeted it at the international market, embracing a further drift from the ephemerality inherent in live television towards a notion of television programmes as an enduring and marketable product.

Whilst many Armchair Theatre plays had strongly emphasised class divides and social inequalities as part of their claim to realism, the adventure series worked to eliminate such concerns. A key factor was the prevailing conditions in the more commercial American television landscape, where networks sought to maximise audiences with programmes that offended the lowest number of people and advertising pressure encouraged a more up-beat and aspirational tone. Many ITC series, including Man of the World, The Baron and the first series of Danger Man, even adopted American protagonists in order to appeal to this market, sidestepping class divides in favour of a more exotic sense of classless modernity.

Yet as the 1960s progressed, such aspirational qualities increasingly corresponded with shifts in British culture. In 1964 the Labour Party won its first General Election in 13 years under the leadership of Harold Wilson, who had styled himself as a moderniser in tune with meritocratic and scientific ideas for managing British society in contrast to perceptions of the Conservative Party as class-bound and anachronistic. Significantly, the following year Danger Man revamped its protagonist John Drake (Patrick McGoohan) into a British agent of ambiguous class, demonstrating his modern sensibility through designer clothes and sleek gadgets. As David Buxton writes, the emergence of pop culture ‘seemed to confirm the utopian possibility of a transcendence of social class in a new society in which relations of consumption were replacing relations of production as the centre of existence’.6 Elsewhere the long-standing tradition of the British gentleman hero was retained with some knowing irony, as in The Saint. The Avengers was able to merge both traditions through its central alliance between the gentlemanly Steed and the modern, liberated Mrs Peel, providing ‘the proof that traditional and modern values can coexist in pure complicity’.7 In the context of the mid-1960s British invasion of the US through popular culture, this combination proved potent, securing The Avengers a prime-time slot with the American Broadcasting Company (ABC-US) and enabling it to become the most popular British drama export of the decade.

During this period filmed series generally adopted a strictly formulaic model with a near-total lack of narrative continuity, ongoing storylines or character development across episodes. In part, this was due to the expense of 35mm film and the wide circulation of such programmes, with a limited number of prints being swapped between different territories, functioning, as critic David Bianculli later wrote, ‘like cards in a deck that could be shuffled and dealt in any order’.8 This is nonetheless indicative of commercial television’s Fordist philosophy towards television series at the time. For the increasingly parodic Avengers, however, this effectively became part of the joke, and Bux...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 ‘A balance of terror’: Callan (ITV, 1967–72) as an existential thriller for television

- 2 ‘A professional’s contest’: procedure and bureaucracy in Special Branch (ITV, 1969–74) and The Sandbaggers (ITV, 1978–80)

- 3 ‘Who killed Great Britain?’: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (BBC 2, 1979) as a modern classic serial

- 4 Conspiracy as a crisis of procedure in Bird of Prey (BBC 1, 1982) and Edge of Darkness (BBC 2, 1985)

- 5 Death of a master narrative: the battle for consensus in A Very British Coup (Channel 4, 1988)

- 6 The precinct is political: espionage as a public service in Spooks (BBC 1, 2002–11)

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index