![]()

Introduction 1

Pedro Almodóvar’s 2011 film La piel que habito (The Skin I Live In) is about a person who does not live in their own skin. The title itself distances the ‘I’ from ‘the skin’ inhabited. It disconnects the metonymic association of a person’s skin with their life or identity made in many languages, for example in English when a person is called a ‘good skin’. Almodóvar’s film suggests a number of themes around skin that are pertinent to this book: skin and identity; the relations between inside and outside; the nude and its colour; artificial skin and fantasies of the human creation of life; skin, touch and the haptic potential of vision; finally, the relationship between skin’s role as a medium and the mediality of the image.

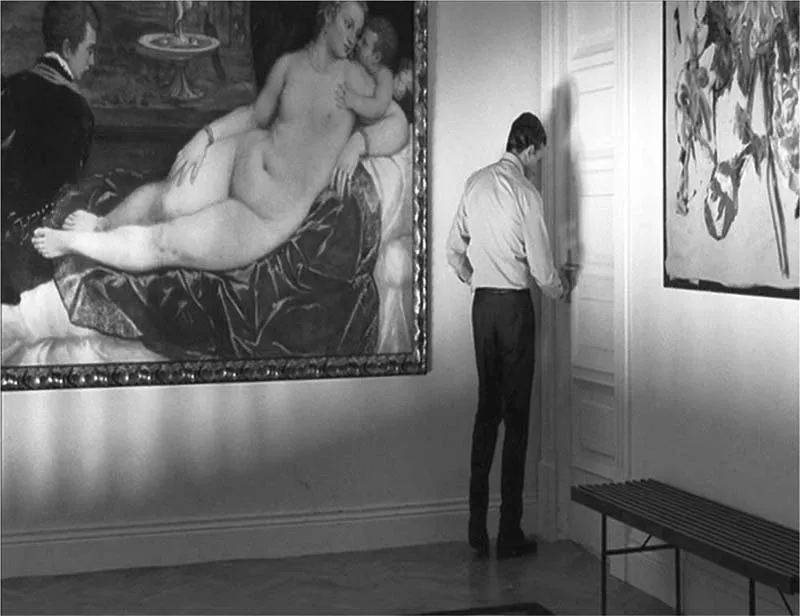

The film starts with views of a well-gated country estate near the town of Toledo in Spain, and quickly moves to images of incarceration and surveillance: walls, grids, modern home security technology and an electronic eye monitoring a woman doing yoga exercises in a beige body suit that fits like a second skin. In a second sequence skin is addressed from a different angle: a physician is lecturing on face transplantation, and Almodóvar announces the disturbing topic of his film by referencing George Franju’s 1960 classic Les yeux sans visage (Eyes Without a Face), a thriller about an obsessed surgeon who in order to reconstitute the disfigured features of his daughter’s face resorts to murder and the harvesting of faces. The two main characters of The Skin I Live In – the plastic surgeon Dr Ledgard (Antonio Banderas) and his involuntary subject named Vera (Elena Anaya) – are brought together just a few moments later, at first indirectly. On a life-size plasma screen the surgeon watches Vera in a pose of a reclining nude seen from the back. He sees her as an image and her immaculate skin as a surface to be slowly sampled with the eye. This mediated encounter has already been prepared by shots of a number of paintings featuring female nudes. As the surgeon climbs the staircase to access his living room, he passes full-size reproductions of two paintings by Titian: The Venus of Urbino (Uffizi) and Venus and Organ Player (Prado) (Figure 1.1). The choice is hardly accidental: Titian’s nudes are classic manifestations of the reclining female body in paint and were copied many times.1 Almodóvar’s film continues this chain of repetitions, as Dr Ledgard’s surgical subject will mimic and perform reclining nudes throughout the film as she lies on her couch reading, fully aware of being watched, and pretending to turn herself into the persona the surgeon desired to create and wishes to see in her (Figure 1.2). Moreover, Titian’s painting, celebrated for the soft and lifelike rendering of the body, is also pertinent to the overall theme of the film, the artificial making of skin. As Daniela Bohde elaborates, Titian was often praised for his quasi mystic ability to transform paint into flesh.2 Vera’s skin, the viewer will learn step by step, is as artificial as painted skin, fabricated by the surgeon and grafted on to the body of a young man.

1.1 Screen shot from Pedro Almodovar, The Skin I Live In, 2011, 1:38:00.

The film weaves a network of relations between skin, flesh and painted or screened images and, later on, analogies are drawn between skin and the medium of film itself. Most of the time, Vera is quite explicitly seen through the eye of a camera. Kept in a luxurious cage, she interacts with the external world only through architectural orifices and technological interfaces: a vacuum cleaner tube installed in a wall, a dumb waiter, an interphone and, most importantly, two surveillance cameras. One of the latter projects black and white images into the kitchen that are monitored by the housekeeper, the other projects high resolution colour images on to the large screen contemplated by the surgeon. This controlled life experiment is interrupted when another person in a different kind of artificial hide enters the scene: the housekeeper’s delinquent and violent, yet beloved, son Zeca who, taking advantage of the carnival season, hides from the police in a tiger costume. He smuggles himself into the secluded estate by sticking out his naked behind to the camera of an intercommunication system thus identifying himself to his mother via a birth mark. The skin underneath the fake fur seems still able to tell the truth, but ends up being the entry ticket for betrayal. Immediately upon entering the house, Zeca is attracted by the image on the monitor showing Vera doing her exercises, and asks ‘What’s that?’ Trying to hide the existence of the captive skin-patient the housekeeper just says ‘it’s a film’, thus suppressing the content by referring to the medium. But it proves an impossible elusion; in Spanish her words are ‘es una película’, employing an expression for film that, deriving from the Latin pelle, literally means little skin. In Roman languages, the thin celluloid membrane coated with photosensitive material and used since the late nineteenth century as a negative film in analogue photography and later for motion pictures took on the name of the organic skin. And though a video such as that produced by the surveillance camera or a digitally produced film like Almodóvar’s is not a film in this strict sense, the word – and with it the analogy with skin – is still present.

1.2 Screen shot from Pedro Almodovar, The Skin I Live In, 2011, 1:46:56.

This connection has already been made by psychoanalyst Didier Anzieu in his 1985 Skin Ego, which has been crucial to numerous subsequent studies on skin:

In its first sense, the French term ‘pellicule’ designates a fine membrane which protects and envelops certain parts of plant or animal organisms; by extension, the word denotes the layer, also fine, of a solid matter on the surface of a liquid or on the outer surface of another solid. In its second sense, ‘pellicule’ means the film used in photography, i.e. the thin layer serving as a base for the sensitive coating that is to receive the impression.3

The psychoanalyst continues that ‘a dream is a “pellicule” in both these senses. It constitutes a protective shield which envelops the sleeper’s psyche and protects it from the latent activity of the diurnal residues and … and from the excitation’ of sensations and physical processes active during sleep. But the película produced by the surveillance camera in Almodóvar’s film fails to serve as a protective shield, and the displacement only hints to what it seeks to conceal. Unwittingly the housekeeper conflates ‘the skin of the film’4 and the skin in the film: the carefully crafted and monitored skin that wraps Vera. The mother can’t stop ‘the tiger’s’ interest in his prey, since he soon sees Vera and thinks he recognises in her features the surgeon’s late wife whom the artificial body uncannily resembles. Driven by a wild attraction that befits his animal costume, he violates all boundaries, breaks into the barred room and rapes Vera. This incursion and multiple penetration of screen, doors and a body triggers a series of flashbacks through which the viewer learns about the history of Vera as well as the surgeon’s late wife and daughter. Gal, the wife, had an affair with Zeca; and, when trying to run away, the couple had a car accident that left Zeca unharmed but Gal barely alive with serious burns. Dr Ledgard – compensating, it seems, with obsessive care and fantasies of surgical omnipotence – makes every attempt to heal his wife. But having made a humble recovery, and unexpectedly seeing her own distorted features reflected in a glass pane, Gal kills herself by jumping out of a window. The suicide leaves its witness – the couple’s little daughter Norma – so traumatised that she needs to be hospitalised and undergo long-term psychiatric treatment. Grown to a pretty teenager and showing signs of improvement, the father takes the unworldly girl to a party where she is approached and raped by a young man himself spaced out by party drugs. The daughter – traumatised again – hides even from her father and returns to hospital. Seeking revenge, the surgeon kidnaps the culprit – Vicente (Jan Cornet) – and uses him for a gruesome experiment: he completely remodels his body, castrating him in a sex change surgery, and grafting an artificial skin made from a mixture of animal and human genes, thus effectively turning Vicente into an artificially engineered body. Ironically, Vicente is renamed Vera, the ‘true one’. From Dr Ledgard’s perspective the experiment is a stunning success: Vera is beautiful, resembles the late wife and has an immaculate skin that looks and feels soft while also being, after a series of improvements, flame proof and pain free. This is the skin the surgeon contemplates on the screen, while stretching on his couch mimicking Vera’s pose, watching her in empathy and admiration for his own work. But that is precisely the trap. Vera is not as docile as Pygmalion’s sculpture Galatea in the well-known story from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a myth of godlike artistic creation. The surgeon’s product – the person with Vera’s features and Vicente’s mind (who never gives up his will to return home) – uses the attraction of their body and the narcissistic pride of their creator to foster his desire. Dr Ledgard imprudently trusts Vera’s love and allows her to live with him, until s/he seizes the occasion to shoot those who held her/him captive.

Skin and identity are explicitly addressed in an early sequence of the film in which Dr Ledgard lectures on new possibilities of face grafts for victims of disfiguring accidents. The surgeon stresses the significance of this kind of surgery because of the crucial role face and facial skin play to a person’s identity. Skin, forming the body’s envelope, demarcation and visible aspect, has indeed often been understood as a safeguard of identity. However, any essentialist notion of identity is undermined in the film, as the surgical proposition is to restore identity via a transplant, with someone else’s face. Still, Dr Ledgard insists on identity in pointing out that the face is a major means of human non-verbal communication and that skin is attached to the muscles that are responsible for facial expression. He thus addresses the function of skin as an interface for transmitting muscular activity and by extension emotions. The ways in which the face can express feelings, or what early modern writers call passions, through movement and colour change (as in blushing or blanching) have also been a major concern for artists aiming to convey psychological motion through outer appearance. The face’s potential to signify has often led to the metaphoric association with canvas and paintings – both face and canvas are surfaces on which colour and line work and produce meaning. Beginning with the French seventeenth-century painter Charles le Brun, artists and physiologists have attempted to codify the passions by aligning specific muscular movements with particular emotions. However, these efforts to manage expression and its pictorial representation could not do away with the challenge that the mobility and transformative character of skin and face brought to artists.

Whether it is about the relatively fixed or rather volatile aspects of the body’s surface, skin serves as a mediator between interior and exterior, as a membrane that communicates and filters physiological and psychological processes located inside. It provides, as Elizabeth Harvey suggests, a ‘complex border between inside and outside, one that emphasises the shifting, dynamic relation between the two’.5 Skin’s role in negotiating the relation between the physical interior and exterior is particularly pertinent in the context of anatomy, where skin has to be literally removed or at least cut open to grant access to the body’s physical interior. In both anatomical texts and images, the skin often becomes a symbol for the practice of anatomy and its way of gaining knowledge through dissection; indirectly however skin also points to anatomy’s conundrum of understanding the living body by studying the corpse. In the practices of artistic anatomy, the skin’s role remains especially ambivalent, as it hides immediate access to the interior while being the medium and instrument of its revelation.

Skin, the body’s tegument, is often conceived as a veil (and vice versa), the physical or symbolic removal of which results in the revelation of an ‘inner truth’ or essence. The removal of the veil stands in for an act of knowledge production that tends to establish what is often a gendered hierarchy between inside and outside that values interiority at the cost of outer appearance. But, as Jacques Derrida reminds us, it is impossible to do away with the veil, especially through an act of revealing: ‘finishing with the veil will always have been the very movement of the veil: un-veiling oneself, reaffirming the veil is unveiling’.6 In his essay ‘A silkworm of one’s own’, Derrida engages instead with the textility of the veil, and any other wrap or woof. In a similar vein, most recent studies of the cultural history of skin have challenged a hermeneutics that seeks to find hidden meanings, and have resisted the assumption that surfaces are invariably superficial.7 From an art historical perspective, looking at skin means looking at surfaces of images, and keeping the materiality of skin as surface and part of the body in play. And it also entails factoring in the materiality of the fabricated surfaces of images.

In Almodóvar’s film the viewers’ customary attempts to read faces and surfaces are frustrated. Vera’s exterior is no faithful expression of the inside. As the story of a person who couldn’t save their own skin, the film can be interpreted as raising the question of what happens when the mind and inner body inhabit a remodelled envelope. The smooth and even skin most people desire to watch and have for themselves turns out to be monstrous. But rather than reiterating the platonic model of the soul trapped in a body, The Skin I Live In leaves its viewers puzzled and even disturbed as to what has become of the I that inhabits the immaculate skin and constitutes its interiority.

Whether the artificial skin still enables Vera/Vincente to have sensory feelings is a question the film leaves, somewhat frustratingly, open. It is the perfect protective barrier, but does it serve as the sense of touch, as is usually the case? Be that as it may, the film certainly activates the sense of touch through the cinematic images of the skin. In one of the scenes in which Dr Ledgard watches Vera on the screen, the camera takes the position of his eyes, and moves towards and across the reclining body. A soft light bathes the skin, and as the film turns more grainy it emphasises the curves and eroticises the body...