![]()

1

The early ‘Miss Jamaica’ competition: cultural revolution and feminist voices, 1929–50

Introduction

The first ‘Miss Jamaica’ beauty competition took place in 1929 and was sponsored by the national newspaper the Daily Gleaner, then closely aligned with planter-merchant interests. The Gleaner’s editor was Herbert G. de Lisser, the most dominant figure in Jamaican literature and publishing, whose reign at the paper extended from 1904 to 1944. ‘Miss Jamaica’ represented an attempt to mark the cultural and racial supremacy of the white-creole planter-merchant class over the rest of Jamaica. This campaign was shaped by de Lisser and sustained through his literary and journalistic publications.

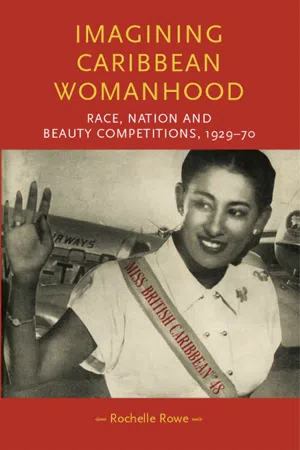

The ‘Miss Jamaica’ beauty contest developed in the 1930s, a decade that witnessed a surge in anticolonial activity: popular uprisings, feminist development, the formation of political parties, and an artistic and literary cultural awakening. However, the ‘Miss Jamaica’ beauty competition did not emerge as part of this cultural revolution, but in resistance to it. The competition became the pre-eminent social gathering among the elite, even as the tumultuous 1930s unfolded around them. However, it also aroused the contempt of middle-class nationalists, including taboo-breaking feminist, poet and playwright Una Marson. Marson attacked the beauty competition and, as her anticolonial position developed, began to interrogate the politics of feminine beauty brought to light by the mood of resistance to British colonialism and the advance of American consumerism in the island. Through an analysis of de Lisser’s dedicated construction of idealised white femininity and Marson’s and her contemporary Amy Bailey’s feminist-nationalist critique of Jamaican national identity, this chapter establishes the context for the origins of a Caribbean beauty competition before the Second World War. Finally it considers the new beauty competitions which emerged immediately after the war and only for a short time: ‘Miss British Caribbean’, and ‘Miss Kingston’. These new competitions projected modified formulations of femininity, through the performance of cultured, modern beauty by women of colour that would signal the islands’ emergence from colonialism.

The Jamaican labour uprisings and political formation

The British civilising mission that sought to mollify the lower classes in post-emancipation Jamaica was only partially successful and the lower classes continued to organise and resist the colonial regime as the twentieth century dawned. However, attempts to organise labour were most successful in the decades between the wars. This period saw the return of ex-servicemen to the island, disillusioned with the black experience at home and abroad, the onset of global economic depression that forced the return of thousands of migrant labourers, and still other migrants leaving rural areas for Kingston in search of work. The unemployed and underemployed converged on the capital’s slums and shanty towns. The city rapidly doubled in size, growing from 117,000 to 237,000 between 1921 and 1943.1

Radical black leader Marcus Garvey, having formed the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in Kingston in 1914, and seen it grow throughout the region and in the United States, returned to Kingston from the US in 1927 as a deportee. The UNIA spread rapidly amongst working people, and became a catalyst for their politicisation and organisation. Garvey won a seat on the Kingston and St Andrew Council, a public representative body, and formed the People’s Political Party, but was unable to breach the Legislative Council in the elections of the following year.2 In addition to Garveyism, other forms of race-conscious nationalism were growing among middle and lower-class blacks. Ethiopianism was an international anticolonial movement, also present in the US and South Africa, which saw free-governed Ethiopia as an affirmative vision of black Africa. Ethiopianism in Jamaica emerged from the anticolonialism of the black churches in the nineteenth century, formerly the basis for missionaries’ model societies.3 Also present in interwar Jamaica was Rastafarianism, formed after the coronation of Ras Tafari as Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia in 1930. The Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 became an important element in anticolonial protest in both Jamaica and Trinidad.4

Jamaican labour protests began on the north coast in 1935 with striking banana workers in St Mary and dockers at the port of Falmouth, protesting against low wages. In the following year the Jamaica Workers and Tradesmen Union (JWTU) was formed among rural peasants and catalysed protests in the countryside. Its leaders were Allan Coombs and Hugh Buchanan, both the sons of rural peasants. Coombs was a former policeman and had served in the West Indian Regiment during the First World War. Buchanan had likely been radicalised in the UNIA.5 By 1937 workers were in open and spontaneous rebellion, with major riots and strikes in Kingston and ‘rolling’ strikes throughout the country.6 This rebellion, reported in the British press, was a major embarrassment to the colonial government, who were increasingly in competition in the region with American imperial interests and sought to appear as benevolent rulers.7 The rebellion provoked a Royal Commission, headed by Lord Moyne, into the causes of poverty and underdevelopment in Jamaica and the wider British West Indies. However, with the outbreak of war, the publication of the report of the Moyne Commission was postponed to 1945.

Coloured middle-class men sought a role in the labour rebellion and by 1937 had emerged as labour leaders, although they were sometimes mistrusted by the lower-classes who had succeeded in organising themselves in much of the action. Alexander Bustamante, for instance, began his involvement as a money-lender to the JWTU, and went on to become a charismatic leader and founded his own eponymous union, the Bustamante Industrial Trade Union. This became the largest trade union and the basis for the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP), which Bustamante also led. His cousin Norman Manley, an Oxford educated lawyer, enjoyed a favourable reputation among the nationalist activists of the Jamaica Progressive League, formed in New York City in 1936, and was committed to British Fabianism, that is to say he favoured a programme for evolutionary rather than revolutionary change, in Jamaica. Manley became leader of the People’s National Party (PNP) when it was formed in 1938. The JLP pursued a populist agenda, and was less disconcerting to the elite, because unlike the PNP it did not pursue the socialist reorganisation of society, only better wages and living conditions for the poor. In contrast, the PNP wanted to stimulate nationalism and socialism in the island and initially appeared the more intellectual party. It attracted middle-class activists in greater numbers than the JLP, which lacked an internal structure for many years, but struggled to persuade its labour following of the need for a unified national identity.8

As both parties grew they lacked meaningful participation from the mass of working people who, though they had provided the initial mandate for the parties’ existence, were denied leadership roles. Instead middle-class proprietorship of the transition to self-government on behalf of a supposedly immature majority black population emerged. This order ignored the rise of race-conscious politics amongst blacks and preferred instead to engender a harmonious national unity. However, though it would be erased in the march towards nationhood, black nationalism had nonetheless provided the impetus for much of the social and cultural activism that thrived during this period.9

Herbert de Lisser, Planters’ Punch and the origins of ‘Miss Jamaica’

Drawing a veil over the social upheaval and cultural awakening that rocked Jamaica during the interwar years, Herbert de Lisser’s ‘Miss Jamaica’ competition instead espoused a narrow nationalism that affirmed the white-identified creole elites. De Lisser’s ideologica...