![]()

1

Learning the ropes

I became a documentary filmmaker by accident. Because of my guitar.

Some people dream of being filmmakers. You know their stories. ‘At the age of three I was making cinemascope films for my parents to show on my birthday. By the age of five I’d built a multiplex theatre out of cardboard, and was showing my epics to my kindergarten friends. By seven I was reprimanded for making my first sex film, etc. etc.’ Well not me. I wanted to go to university and be a lawyer. My parents liked this idea. Maybe I could keep them in their old age.

In due course I went to Oxford, and studied wonderfully useful courses such as Roman law. So I learned how to manumit (free) a slave, and what legal action to take when a table fell on you. You punished it by sawing off a leg. Eventually, trying to delay that fatal day when I would actually have to go out to work, I got accepted at Stanford Graduate Business School to study for an MBA. Then fate intervened.

In order to supplement a scholarship given to me by Stanford, I used to play the guitar and sing at local folk clubs, and at parties. Having been born in England and having a British accent was useful, especially when singing bawdy Elizabethan songs. However, the most popular songs, if there were a lot of married couples present, had verses like ‘When I was single, my pockets did jingle, and I wish I was single again, again … I wish I was single again.’ Of course, those were the days before political correctness became the rage.

Anyway, after one of these song sessions, someone asked me to come and sing at a small TV studio in San Francisco. Well, why not? The session went well, but one thing surprised me: the technicians handling the cameras were all students. This definitely needed investigating further, so I asked two of them out for coffee. Over a ghastly brew that in no way resembled coffee (those were the pre-Starbucks days) I asked Nancy and Dick what their appearance at the TV station was all about. The answer was simple. They were taking an MA in film at Stanford. Well, not actually in film; in theatre and communications, but film and TV studies were a major part of the curriculum.

Now, as I told you, I hadn’t been a film buff at the age of three, but I had wasted a lot of time during my law studies watching Bergman, and had at one time contemplated applying for a job at the BBC. If film was being taught at Stanford, maybe I could combine that with my business studies. It was an interesting thought, so I went off the next day to see the Stanford head of film studies. And did he sell me a bill of goods!

According to the good Prof., graduates of the Stanford program were working as directors at ABC and NBC head offices in New York, were tracking across Afghanistan with cameras as we spoke, were managing a few British studios, and were rising to the top in Warner Brothers and Paramount. Now I am as gullible and as starry-eyed as the next guy, so without more than five minutes thought I signed on to do a minor in film. Then came the surprises.

When I went to inspect matters more closely I found the film department consisted of about ten students, and was taught by two or three instructors who had probably worked in film before Methuselah’s time. As for film equipment, that was something else. The department had one wind-up Bolex camera that took 100 foot spools. It had three broken-down lamps, resting on battered stands, and an ancient splicer. As for sound, forget it. There was no proper sound recorder on which you could do sync, though there was a small tape recorder for wild sound.

In short, the situation was pretty awful, and I would have quit in a week except for one man. This was a young instructor called Henry Breitrose, who was an inspiration. He made you believe that in spite of the lousy equipment you too could become a Bergman or a Hitchcock. Or, more precisely you could become a Flaherty or a John Grierson, because, as I was to learn, the emphasis of the department was on documentary.

So, we had rotten equipment, but I loved it, and lapped up everything I could read and learn about filmmaking. I went out and learned how to handle the Bolex, and shot a film on dance. In the small department cellar I learned how to use the splicer and glue to make primitive cuts. I learned that when you lose the tapes with all the music you’ve selected, Vivaldi will always work instead. And I directed a film on three artists. Put simply, I was stupidly in heaven.

In reality, Stanford gave me a tremendous enthusiasm for documentary, but taught me little about technical matters.1 Most of my real film skills and know-how I picked up later, starting in New York.

In order to get a film degree at Stanford, one of the requirements was that you had to work for three to six months in a real professional situation. To satisfy this obligation I worked for a while as a general studio hand at KQED in San Francisco, then headed for New York to work with an experimental filmmaker called Shirley Clarke. This didn’t work out, but instead I met another director called George Stoney who took me on as a camera assistant to a man called Terry Macartney-Filgate.2

Though I didn’t realize it at the time, I was working with one of the great documentary cameramen of the sixties. A pioneer of cinéma vérité, Terry had shot some superb films for the National Film Board of Canada, including the two classics, Blood and Fire and The Backbreaking Leaf. He had also joined Ricky Leacock and Don Pennebaker in filming Primary, about John Kennedy. So I was learning from a true master.

Terry taught me two things: how to enjoy New York, and how to shoot. And maybe the first was most important. Together with Terry I roamed Manhattan from Riverside Drive down to Wall Street. Often, to my astonishment, he would turn his raincoat around and rush up Broadway pretending to be Batman. He knew all the bars, the best and cheapest restaurants, and what to see and where to go. Among other good treats he introduced me to McSorley’s Old Ale House. At the time no women were allowed, the floor was covered in sawdust, the standard meal was boiled beef and cabbage, and the waiter automatically brought you two beers. To have had only one would be to admit you weren’t a man.

Though quite a prankster in his spare time, Terry was all concentration when we worked together on George’s film about New York problems. Much of the time he hefted an Arriflex 35mm on his shoulder as he shot with a long lens down Broadway to Times Square, or in reverse up to Columbus Circle. Always he would explain why he used a particular lens for a shot, and what its effect would be. He was a great enthusiast for back lighting, and introduced me to its charms, particularly if the picture was slightly under-exposed. He also taught me when and when not to use a tripod, what to look for in people, and how to interview and talk with the camera in your lap. But as much as all the technical lessons, I also absorbed a great deal from Terry about documentary in general, what to look for in any situation, and how to structure a film.

Unfortunately we only had three months together before I left for England to see my family. I had surprised them a bit with my turn towards film, but my father was always encouraging, and just told me to work hard and keep away from wild women. I’m not sure what he meant by the latter words, but I told him I’d keep that thought in mind.

To earn a bit of money I started writing feature articles for the newspapers, about odd aspects of life in the USA. These included articles on visits to huge American secondhand car sales parks; the performance of cheerleaders at football games; Beatnik San Francisco; modern hunters for gold in California who used scuba-diving equipment in their searches, and even how to buy a telephone in Chicago. If these subjects seem banal, one has to remember that to us Brits, the USA was another and very strange planet in those days.

The question of how to continue my film career after getting home was answered when I met a guy called Peter Cantor at a party in London. Peter worked as an editor for the BBC, and wanted to go to Israel and shoot a film about watering the desert and life on a kibbutz. He had an old Bolex camera and had collected about 5,000 feet of black and white film from his BBC cameraperson friends. Added together that amounted to about two hours of raw stock. This material was made up from odd snips of unused end film from the standard 400 foot reels everyone shot with. When Peter heard I had studied film at Stanford, he didn’t enquire what that meant, but just asked immediately ‘Do you want to come with me and shoot?’ Well we were both a bit sozzled, and I hadn’t found any of Dad’s wild women at the party to distract me, so immediately said yes.

Our first action was to print visiting cards that said ‘World Television Documentaries.’ We knew we would need them to make an impression in a strange land. The card was a bit over the top, but my father always said ‘If you’re going to go for it, go for it big!’ And the cards worked, at least at the Israeli Embassy, where we’d asked for a meeting with the cultural attaché. He listened with sympathy to our story about being BBC filmmakers (well at least Peter was), who wanted to make a film about water and kibbutz life, and promised us help. In the end, when we got to Tel Aviv that meant a government car to take us around, and even free air flights.

I enjoyed Israel, which was hot, dusty, and dirty, but which exhibited colours and a landscape straight out of Van Gogh. We shot everywhere, in the mountains of the north, and in the deserts of the south, in the kibbutzim, and in the towns. Occasionally I would shoot and Peter would direct, and then after a day or two we’d swap roles.

When we got back to England two-thirds of the footage was usable, and the rest was awful. Peter then edited the film in his spare time and we sold it to the BBC. It was my first successful sale, and I thought maybe there was a future to this craziness. Technically both Peter and I learned a lot from our mistakes, and especially from the badly shot and dumped footage. But the best thing we learned was that sometimes you had to take a gamble. So the making of our outrageous visiting cards had been a bit impetuous, but their use had got us into strange places, and certainly saved us a lot of money.

In spite of my hopes I found it difficult to get entry into the BBC, so decided to complete my legal training and qualify as a solicitor (the equivalent of the American attorney who pleads in the lower courts and handles business legal matters). I then went to work in a law office that dealt with a lot of film matters, mainly financing, but kept my producing film interests on a low burner.

To this end I taught evening courses for the British Film Institute (BFI), which included teaching the staff at the John Lewis store in Oxford Street how to make films. This was a strange but wonderful experience as everyone came in grey suits, and in class called each other by their surnames. I also journeyed for the BFI to Birmingham or Coventry to lecture on documentary and show clips from the films of Eisenstein or Humphrey Jennings. To complement all this I also made a few low-budget films on the side. This was all going well till I got a life-changing call asking me whether I wanted to go to Jerusalem and help set up a television station there. Again madness took hold and I decided to leave my law office and go, and have recorded the insanity but fun of my year and half with Israel TV in Jerusalem, Take One!3

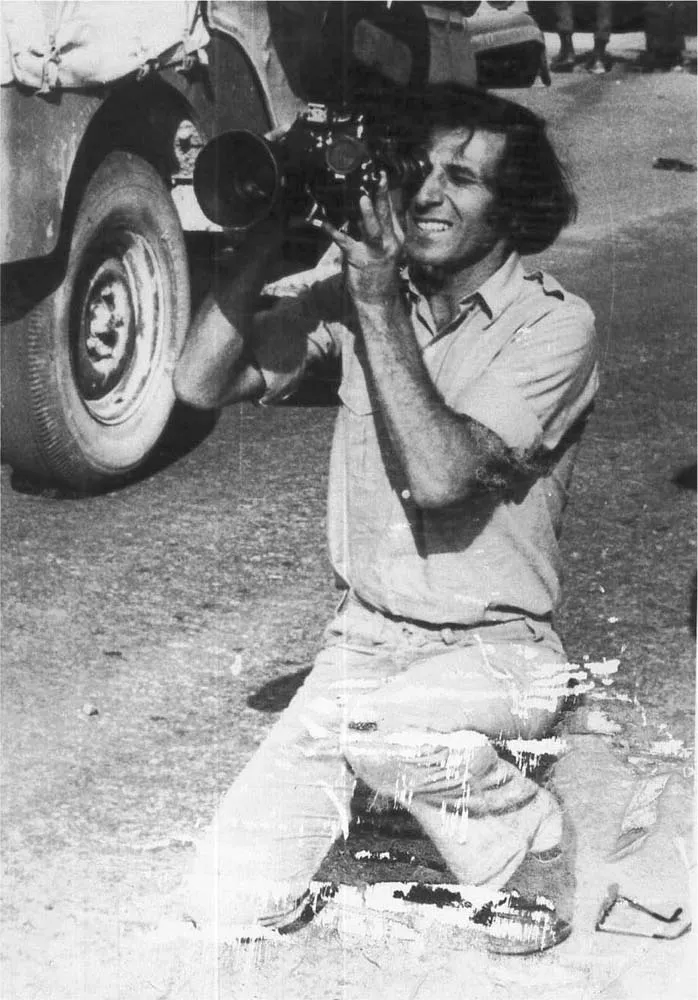

2 The author filming at the Suez Canal during the Yom Kippur War.

After life in Jerusalem I took a job for two years teaching documentary film at York University in Toronto. This was because I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to return to law, or go on with serious filmmaking. Israel had been fun, but the situation at the TV station had been totally chaotic, and didn’t promise well for the future. Toronto gave me time out to think.

While reviewing my own background and film education I realized that, apart from working with Terry and George Stoney, I hadn’t seen much of other filmmakers at work. That was obviously a grave omission, but also gave me an idea for my first book. Why not talk to fifteen to twenty filmmakers and simply interview them as to how they made their films, and ask them about the problems they encountered? Such books are common these days, but they weren’t then, and I thought if I could write a good outline a publisher might take it. I also thought I would learn a tremendous amount in the process, which turned out to be true.

Having come to the conclusion that such a book might work, I sat down to consider whom I could approach. Cinéma vérité had become very popular which argued for talking to Fred Wiseman, Don Pennebaker and Albert Maysles. These were the new observational filmmakers who were turning conventional documentary on its head. There were also a few good people at NET New York, the educational broadcaster, to whom I thought might be worthwhile speaking, such as Mort Silverstein, and Arthur Barron. Then there were the Brits, who were totally unknown in the States, but had done some incredible documentary work. Here I was thinking of people like Jack Gold and Peter Watkins, who had made a great film about an atom bomb falling on England. Peter’s film, The War Game, had caused a major controversy, and had basically been banned by the BBC even though they had commissioned it. If I could get Peter to speak to me about his problems I thought it would be a major contribution to the book.

The War Game also came under the genre of docudrama, a kind of hybrid between documentary and pre-scripted dramas with actors. I knew little about the genre and thought its techniques well worth exploring. To this end I added another great British docudrama film to my list, Cathy Come Home, which was a fiction film about the homeless, based on true life incidents. The film was written by Jeremy Sandford and directed by Ken Loach. Loach I never met, but I became quite friendly with Jeremy who taught me a great deal about dramatizing reality.

One of the subjects I really wanted to explore further in the book, was the relationship between members of the documentary film team. Most articles I’d read concentrated on the director’s view, but now I wanted to go a bit deeper, and see how the director related to the rest of his crew. With this in mind I did a number of multiple interviews discussing the same film. The most interesting experience here was discussing the Canadian film A Married Couple with the film’s director Alan King, and his photographer and editor. A Married Couple can be considered the inspiration for series like An American Family, but has never been given its due. I also looked at the director–editor relationship in two other films, Salesman and What Harvest for the Reaper. Gradually it became clear to me that, at least in cinéma vérité films, which were then the rage, the director often had only a vague idea of the film’s backbone, and many a time had to leave it to the editor to find the central theme and story of the film. The lesson here for me, which has continued to this day, is that the main work in documentary is thinking about where you’re going and what you want to do before you ever start shooting.

Two other key lessons emerged for me from the interviews, the first of which actually follows on from what I wrote in the last paragraph. This was an approach, taught to me by Arthur Barron, which came out of our discussion of his film The Berkeley Rebels. Arthur insisted on the necessity for deep research and really getting to know your subject, and then writing a detailed note on the form and shape...