eBook - ePub

After 1851

The material and visual cultures of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham

This is a test

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

After 1851

The material and visual cultures of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Through addressing the history of Crystal Palace at Sydenham, this collection provides a valuable review of nineteenth-century visual and material culture. It broadens our understanding of how exhibitions were constructed, mediated and consumed and contributes to emerging critical debates about modernity and Modernism in the early twentieth century.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access After 1851 by Kate Nichols, Sarah Victoria Turner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Kunst & Kunstgeschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

‘What is to become of the Crystal Palace?’ The Crystal Palace after 1851

Kate Nichols and Sarah Victoria Turner

‘The 10th of June, 1854, promises to be a day scarcely less memorable in the social history of the present age than was the 1st of May, 1851’, boasted the Chronicle, comparing the opening of the Crystal Palace, newly installed on the crown of Sydenham Hill in South London, to that of the Great Exhibition (figure 1.1).1 Many contemporary commentators deemed the Sydenham Palace’s contents superior, the building more spectacular and its educative potential much greater than its predecessor.2 Yet their predictions proved to be a little wide of the mark, and for a long time, studies of the six-month long Great Exhibition of 1851 have marginalised the eighty-two-year presence of the Sydenham Palace.3 This volume looks beyond the chronological confines of 1851 to address the significance of the Sydenham Crystal Palace as a cultural site, image and structure well into the twentieth century, even after it was destroyed by fire in 1936.

The Crystal Palace at Sydenham, both as complete structure (1854–1936) and as ruin, does not belong exclusively to any one period. It was an icon of mid-Victorian Britain, but at the same time embodied from its inception architectural innovation and modernity – what Henry James described in 1893 as its ‘hard modern twinkle’.4 The chapters in this book provide close case studies of the courts, building, gardens, visitors and workers at the Sydenham site, spanning 1851 to the early twenty-first century. Examining a wealth of largely unpublished primary material, this collection brings together research on objects, materials and subjects as diverse as those represented under the glass roof of the Sydenham Palace itself; from the Venus de Milo to souvenir ‘peep eggs’, war memorials to children’s story books, portrait busts to imperial pageants, tropical plants to cartoons made by artists on the spot, copies of paintings from ancient caves in India to 1950s film. The chapters do not simply catalogue and collect this eclectic congregation, but provide new ways for assessing the significance of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham for both nineteenthand twentieth-century studies, questioning the caricature of a twentieth-century cultural revolt against the ‘Victorian’.

1.1 Postcard of the Crystal Palace, early twentieth century. Author’s collection.

The Sydenham site offers cultural and social historians a vast and largely unexplored archive showing the intersections of leisure, pleasure and education, articulated through the dazzling display of imperial, industrial and artistic material culture. The visitors were as diverse as the exhibits.5 Part of the Palace’s allure, especially for middle-class commentators, was the frisson of this social mix, which encompassed the British working, middle and upper classes, international tourists and diplomats, exhibited peoples from across the Empire, through to members of the Royal Family who were regular and avid attendees (figure 1.2). Chapters in this volume argue for the importance of the Palace in understanding early formations of mass culture in Britain. Echoing the question posed by Joseph Paxton, architect of the 1851 structure, at the close of the Great Exhibition, ‘What is to become of the Crystal Palace?’ this book argues that there is considerable potential in studying this unique architectural and art-historical document after 1851.6

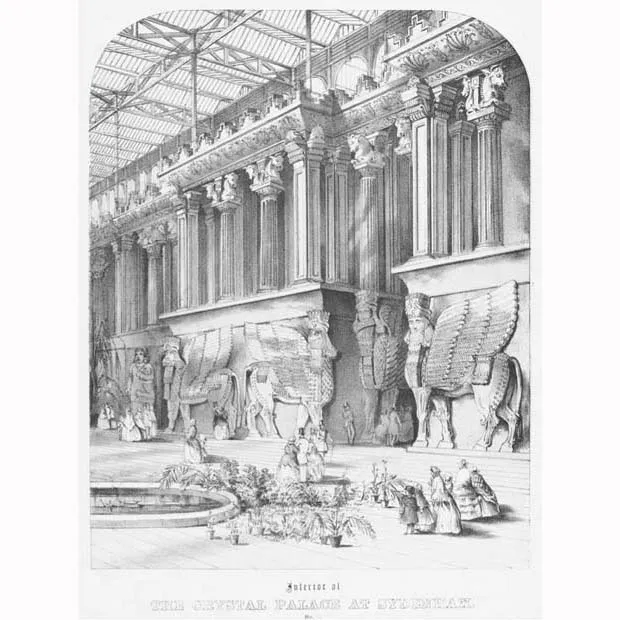

1.2 A mixed group of women, men and children in front of the Nineveh Court at Sydenham. Anonymous, ‘Interior of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, number 8’, lithograph, 1854. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Through a series of display rooms, clearly delineated on the ground plan, and described in the guidebook and much subsequent literature as ‘courts’, the directors of the Palace sought to present an ‘illustrated encyclopaedia of this great and varied universe’ (figure 1.3).7 In his widely reported opening speech, Palace company director Samuel Laing set out the mission of visual instruction combining what he claimed was ‘every art and every science’.8 The organisers hoped that visitors would not simply wander aimlessly (although many presumably did), but would participate and learn through a systematic encounter with a carefully selected display of objects in a curated and highly managed environment – what Jason Edwards describes in his chapter as ‘an eclectic, cosmopolitan world system’. This combination of a serious educative purpose with mass entertainment, designed with pleasure and crowd pleasing in mind, was something of a hallmark of the Sydenham Palace. As Matthew Digby Wyatt, one of the architects of the Fine Arts Courts, put it, the displays at Sydenham were designed to educate ‘by eye’, as well as to be a source of ‘stimulating pleasure’.9

The Crystal Palaces

The memory of what art historian Lady Elizabeth Eastlake described as that ‘old friend’ the Great Exhibition lived on in visitors’ recollections, contributing towards the horizon of expectations that many brought to a visit to Sydenham.10 The Palace of 1854 certainly had an umbilical connection to 1851. The design-reforming zeal of the Great Exhibition continued at Sydenham with a crossover of personnel. Matthew Digby Wyatt and his fellow Fine Arts Court architect Owen Jones, had also decorated the interior of the 1851 building, and theorised the connections between objects of art and industry that both palaces contained.11 Scholarship has frequently conflated (and sometimes mistaken) the Sydenham Palace with the Great Exhibition, despite the fact that the Sydenham Palace displayed entirely different material on different organising principles, was larger, and had additional architectural features such as the highly visible water towers. The chapters in this collection attest that the Crystal Palace post-1854 needs to be understood as an enterprise quite distinct, with very different aims, and different adaptations during its long lifespan across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The Sydenham Palace was built in an 1850s design-reforming moment, but it formed as much a part of the later Victorian and Edwardian cultures of museum visiting, archaeological reconstruction, sports participation and spectatorship, amusement parks, shopping centres and pet shows.

1.3 Ground plan of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham in 1854, Illustrated London News (17 June 1854), p. 581. Author’s collection.

The ever-developing and extensive nature of the Sydenham Palace poses problems of how to study, describe and assess the contents within the interior courts, as well its vast grounds. As Verity Hunt explores in Chapter 2 of this book, since its inception in the nineteenth century, authors have frequently commented on the challenges of describing the Palace, due to a combination of its physical size, its architectural novelty and the diversity of its displays and exhibits. The record and recollections of the Palace’s high turnover of participants, viewers and performers is now scattered across collections of ephemera, in personal archives, published letters and diaries, in the local history libraries of South London and in a handful of official documents in the London Metropolitan Archives and at the Guildhall.12 Even its very building fabric, glass, as Isobel Armstrong has explored, is contradictory and many-faceted, claiming transparency and industrial modernity, but riddled with the ‘scratches, fingerprints … impurities and bubbles of air’ that testify to its production by human breath.13 Jan Piggott’s The Crystal Palace at Sydenham 1854–1936 (2004) was the first publication to offer a comprehensive history of the multifaceted life of the Palace, inside and out, to accompany an exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, and is an essential point of departure for all chapters here. This collection aims to evoke the eclecticism of the Palace on Sydenham Hill in bringing together the research of scholars from the disciplines of art history, English literature, classics, digital humanities, film studies and the history of science.14 The chapters in this volume consider parts of the Palace less well explored; not just specific courts but the relationships among permanent Fine Arts Courts and shifting displays, representations and responses to the Palace, both inside and outside.

Visiting fairyland

‘What it will be when the sound of the workman’s hammer has ceased, and the decorative artist has put his last touches to its ornaments, and it is filled with “gems rich and rare” from the four quarters of the world, one can only imagine: we must wait to see’, wrote a commentator in the Art Journal.15 Anticipation ran high in the lead-up to the Palace’s opening, and the press presented it as a site worthy of pilgrimage. Alighting at the newly completed Low Level railway station, the Crystal Palace experience began before entering the building. Eager visitors peering through the train windows for a glimpse of the Palace might have caught sight of one of the ‘monsters’ that formed part of the display of geology on the lower lake even before the train pulled into the station. Railway enthusiast and imperial electrical engineer, Alfred Rosling Bennett, recounting in 1924 his first visit to the Palace at the age of eight, noted the mounting excitement he felt on disembarking the train in 1858:

The platforms were at a considerable distance from the Palace proper, but, being joined to it by long glass corridors embellished with flowers and climbing plants and affording views of the beautiful grounds, the hiatus was not much felt; indeed, it served to heighten expectation by avoiding a too rapid transition between the prosaic puffer and fairyland.16

Bennett suggests that the glass corridor linking the station and the Palace prepared the visitor for the otherworldly environment of the Sydenham site. Climbing the 700 stairs of the corridor, visitors would pop up, no doubt short of breath, into the Natural History Department in the south nave, with its tableaux of brightly painted plaster casts of non-European peoples. These had been arranged by Vice-President of the Ethnological Society, Robert Gordon Latham and were displayed alongside stuffed exo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of contributors

- Foreword by Isobel Armstrong

- Acknowledgements

- 1 ‘What is to become of the Crystal Palace?’ The Crystal Palace after 1851: Kate Nichols and Sarah Victoria Turner

- 2 ‘A present from the Crystal Palace’: souvenirs of Sydenham, miniature views and material memory: Verity Hunt

- 3 The cosmopolitan world of Victorian portraiture: the Crystal Palace portrait gallery, c.1854: Jason Edwards

- 4 The armless artist and the lightning cartoonist: performing popular culture at the Crystal Palace c.1900: Ann Roberts

- 5 ‘[M]anly beauty and muscular strength’: sculpture, sport and the nation at the Crystal Palace, 1854–1918: Kate Nichols

- 6 From Ajanta to Sydenham: ‘Indian’ art at the Sydenham Palace: Sarah Victoria Turner

- 7 Peculiar pleasure in the ruined Crystal Palace: James Boaden

- 8 Dinosaurs Don’t Die: the Crystal Palace monsters in children’s literature, 1854–2001: Melanie Keene

- 9 ‘A copy – or rather a translation … with numerous sparkling emendations.’ Re-rebuilding the Pompeian Court of the Crystal Palace: Shelley Hales and Nic Earle

- Index