![]()

1

Introduction: the same-sex unions revolution in western democracies

On 1 October 1989 eleven gay male couples gathered in the registry office of Copenhagen’s city chambers to do what no other same-sex couples in modern history had done, namely take part in a civil ceremony to have their relationships recognised by a state. The civil institution these couples were entering was not officially marriage, but rather a newly established entity called a registered partnership (RP). The ceremony the state had created in order for them to enter this new institution, however, was almost identical to the one that heterosexual couples perform when getting married. The eleven couples did their best to reinforce this impression by dressing in traditional marriage attire and arriving in horse-drawn carriages. The first couple to register was the long-time gay activists Axel and Eigil Axgil, who had been together for over forty years and had foreshadowed their pioneering role in gay and lesbian history by adopting a common last name some thirty years before the Danish state officially recognised them as a couple. The event was carefully stage-managed by the Danish gay rights organisation, the National Organisation for Gays and Lesbians, and their meticulous planning paid off. The international media turned out in great numbers and sent photos of these first ‘gay weddings’ circulating throughout the western world (Rydstroem, 2011: 53–4). Without intending to do so, the Danish state sparked a revolution in how western democracies recognise and regulate the relationships of the same-sex couples who live within their borders.

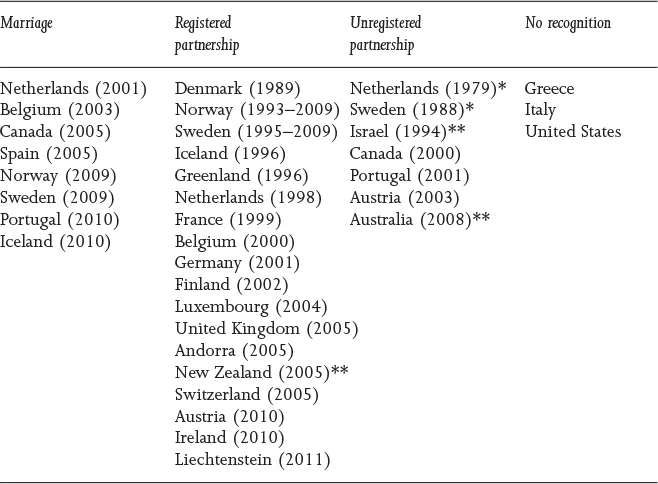

In the two decades that have passed since that October day, nineteen additional democracies in Western Europe and North America have implemented national same-sex unions (SSU) laws.1 Indeed the only western democracies that do not have such legislation in place at the national level are Greece, Italy and the United States.2 Although politics scholars have paid it relatively little attention, this wave of adoption of SSU legislation represents one of the most striking cases of convergent policy change in recent times. These broad processes of convergence, however, have not led to identical outcomes. A small minority of western democracies do not extend any form of recognition to same-sex couples. Further, the western countries that have adopted SSU policies have structured these laws in a variety of ways. An increasing number have opened civil marriage to same-sex couples, but most adopter countries have implemented RP schemes with varying levels of benefits and recognition. Still others have adopted unregistered cohabitation laws that generally bestow fewer rights and duties on gay and lesbian couples (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 National SSU policy in western democracies, 2011

Sources: Bruce-Jones and Itaborahy, 2011; Waaldijk, 2005.

* Both the Netherlands and Sweden adopted legislation before 1989 that recognised same-sex domestic cohabitants for certain legal purposes. This legislation was piecemeal and limited in nature until well into the 1990s.

** Australia, New Zealand and Israel have not been included in this study for largely practical reasons.

Given these dramatic policy developments this study seeks to address three related questions: (1) How can we explain the wave of SSU adoptions that has occurred across western democracies since 1989? (2) Why has a minority of western democracies failed to adopt such a law or been laggards in doing so? (3) Why have adopter countries implemented different models of SSU recognition? My central contention in this book is that processes of international norm diffusion and socialisation have been an important catalyst of SSU adoption in western democracies. More specifically, and in keeping with theories of international socialisation, I argue that the creation and dissemination of a norm for same-sex relationship recognition in the broader European polity in the mid 1990s have focused national lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT)3 movements on SSU policy, allowed these movements to frame state relationship recognition as a human right and helped activists to put SSUs on their country’s political agenda. Further, the dissemination of the norm has induced many national policy elites to internalise its core principle of equal treatment and has helped these elites to justify their own proposals to recognise gay and lesbian couples in national law. The fact that thirteen western democracies have adopted an SSU law since 2000 is not a mere coincidence; these are related events. How and to what extent they are related, however, are more complex questions. By examining the role that these international influences have played in the adoption of SSU laws, as well as why differences still exist across western democracies in terms of recognition and models of recognition, this study will unravel the complex ways in which international norms shape (or fail to shape) domestic policy outcomes.

To develop this argument and address the three questions outlined above I examine LGBT human rights policy since the 1980s at the international and European levels, as well as within eighteen western democracies.4 This broad-based examination reveals that processes of international socialisation and social learning have strongly influenced SSU adoption in most but not all the adopter countries. It also reveals that differences in culture – especially differences in religious values and perceived legitimacy of international norms – play an important role in determining how governments and publics have reacted to calls for relationship recognition and to a lesser degree which SSU model adopter states have chosen to implement. To tease out the precise mechanisms by which processes of international socialisation have shaped domestic SSU policy, I follow this broad-based analysis with in-depth case studies of four countries (Germany, the Netherlands, Canada and the US) in which national SSU policy outcomes have varied in terms of adoption and models adopted. These case studies also serve to better illuminate why countries have adopted different models of relationship recognition, and in particular why a growing minority of western democracies have opened marriage to same-sex couples.

In making these arguments the study contributes to a number of prominent contemporary debates in the discipline of politics. Perhaps most obviously the monograph’s findings add to an emerging literature on LGBT politics within political science. Although sociologists and sexuality scholars have written extensively about LGBT identities and movements, political scientists have been somewhat slow to add gay and lesbian politics to their research agendas. This story of relative neglect, however, has begun to change. Since the mid 2000s political scientists have published a growing number of studies on LGBT rights politics (Rayside, 2008; Smith, 2008; Badgett, 2009; Rydstroem, 2011; Tremblay, Paternotte and Johnson, 2011). These works elucidate the political processes that have led to the expansion of LGBT rights in certain western democracies, but most have concentrated on developments in just one or two countries. As a result much of this literature overlooks the broader international context in which SSU adoption and LGBT rights expansion has taken place. This study seeks to add to this literature the crucial insight that SSU policy in western democracies cannot be explained by domestic politics alone.

More broadly the monograph addresses a number of prominent debates in comparative politics and international relations (IR) about the power that international norms have in domestic settings. I draw on constructivist theories of international socialisation to describe the emergence, dissemination and internalisation – in certain western democracies – of the relationship recognition norm described above. Although the book’s findings largely confirm constructivists’ key claim that international socialisation can influence domestic policy outcomes, the study also refines and challenges some of the conventional wisdoms about how this process happens. First, the study adds to constructivist work on the international human rights regime, which has been a prominent focus of the literature.5 The SSU case demonstrates that human rights norms developed within international organisations and promoted by transnational advocacy networks can influence the internal policies of established democracies. Most scholarship on the topic has focused either on the human rights practices of authoritarian regimes or the foreign policies of western democracies towards human rights-violating states. Very little work examines the human rights policies of these democracies themselves. The book’s findings show that the human rights regime does not simply serve to spread well-established principles to an ever-increasing number of countries outside the western world. The regime evolves over time and incorporates new norms of proper state behaviour that have effects in established democracies. The processes by which human rights norms influence these liberal democracies, however, are often less instrumental than is portrayed in the literature on the international human rights regime (Risse and Sikkink, 1999). In cases where the target states are relatively rich in terms of power and international status, material threats or rewards are often not available as tools for ensuring norm compliance. Rather governments have to be persuaded of the legitimacy of the new norm.

Second, the study enhances our understanding of the precise mechanisms by which international norms catalyse domestic policy change as well as how domestic political systems translate this international normative pressure into specific national outcomes. These questions of domestic norm reception remain perennially under-developed in constructivist accounts of international socialisation in part because IR scholars are often ill-equipped to engage in the study of domestic politics. I utilise concepts developed by comparative politics and social movement scholars such as domestic policy discourse and discursive opportunities to flesh out the mechanisms by which international norms influence national policy debates. Finally, the SSU case demonstrates the importance that culture – both broad patterns of societal values and more narrow notions of political culture – plays in the domestic reception of norms and policy change. The institutional turn in political science has led to the domination of structural explanations in comparative politics and international relations. Studies of domestic norm reception by IR scholars have tended either to conflate structure and culture in their definitions of domestic traditions or have ignored values-based variables altogether. As the analysis in this study makes clear, SSU policy debates, in which concerns about economic interests have played second fiddle to the symbolism of state recognition of same-sex couples, are heavily influenced by prevailing cultural values.

The rest of this introductory chapter unfolds as follows. The next section gives a brief overview of recent developments in LGBT politics as well as the academic literatures that seek to interpret and analyse these developments. Section three summarises the arguments I develop in the book to address the study’s three overarching research questions outlined above. Section four describes the methods and evidence used to make the study’s core claims and justifies the selection of the study’s country cases. The chapter ends with a brief description of the manuscript’s six remaining chapters and how the central argument is developed within them.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender politics: bringing the international dimension in

The nature and substance of LGBT politics in western societies have undergone dramatic change since the 1980s. In many countries these changes began with the rebranding of prominent western LGBT associations as explicit human rights organisations. Although rights rhetoric always has been part of twentieth-century gay and lesbian activism, the sexual liberation movements that burst onto the scene in many western countries in the 1970s often were as focused on broader cultural change as on legal reform. Many activists of the era, particularly those allied with the new left student protests, openly derided a civil rights framing of the gay and lesbian movement as being too assimilationist and rooted in bourgeois and patriarchal values. By the late 1980s, however, the rise of neoliberal norms, the sobering effects of the HIV-AIDS epidemic and the strengthening of the international human rights regime led many LGBT activists to adopt human rights as their central organising principle. Several rights-oriented LGBT organisations such as the Lesben- und Schwulen Verband in Deutschland (Lesbian and Gay Federation in Germany; LSVD) in Germany, the Human Rights Campaign Fund in the US and Stonewall in the UK were created during this period and became the motor of national movements in these countries (Adam, Duyvendak and Krouwel, 1999). Although increasingly dominant, these rights-based groups remain one strand of very diverse movements. The late 1980s, for example, also saw the rise of queer activism in some countries, which drew on the socio-cultural critiques and ambitions of the earlier liberation activists and has remained very critical of the conservatism of the human rights framing of sexuality movements.

The increased strength and visibility of national LGBT movements coincided with an expansion of the rights and legal protections enjoyed by gay men, lesbians and transgenders in almost all western democracies (see Table 1.2). By 1980 sexual relations between people of the same sex had been decriminalised in most western countries, although many governments maintained higher ages of consent for same-sex relations or anal sex well into the 2000s (Bruce-Jones and Itaborahy, 2011). In the late 1980s and early 1990s the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) compelled laggard states such as the UK (Northern Ireland), Austria, Ireland and Cyprus to decriminalise sex between consenting adult men (see Dudgeon v. United Kingdom; Norris v. Ireland). In later rulings the ECtHR further mandated that member states maintain equal ages of consent for same-sex and different-sex sexual activity (Sutherland v. UK). In the US, which is not subject to the rulings of the ECtHR, sex between two men was not decriminalised in all regions of the country until as late as 2003. Laws that allow for unequal ages of consent still exist in several US states, as, perhaps more surprisingly, is the case in certain Canadian provinces where sex between two men has been legal since 1969 (Bruce-Jones and Itaborahy, 2011).

In the 1990s and 2000s a number of western democracies for the first time also adopted anti-discrimination legislation that prohibits sexual-orientation discrimination in the workplace and in some countries in the provision of goods and services. Such legislation first appeared in the Netherlands and the Nordic countries, but soon spread to other European states. Since 1980 fifteen western democracies have enacted such legislation at the national level in part as a result of European Union (EU) legislation. Portugal, Switzerland and Sweden now also include sexual orientation as a protected category in their national constitutions (Bruce-Jones and Itaborahy, 2011). In Canada sexual orientation was ‘read into’ the Equal Protection clause of the national constitution in the late 1990s, which has led to a dramatic expansion of LGBT rights during the first decade of the twenty-first century. Several US states also have comprehensive anti-discrimination laws in place. The national constitution, however, has not yet been interpreted to afford strong protections against sexual-orientation discrimination, although there has been movement in that direction in case law since 2010. More recently, several European countries have extended these anti-discrimination protections to include gender identity for transgenders. At present seventeen European countries – both East and West – offer such protections in one form or another (Bruce-Jones and Itaborahy, 2011).

Perhaps the most remarkable development in LGBT rights politics in terms of scope, rapidity and profile has been the change in the legal recognition of same-sex couples. No fewer than twenty western democracies have created legal institutions to recognise same-sex couples since 1989. The Danish RP example quickly was copied by other Nordic countries: Norway in 1993, Sweden in 1995 and Iceland in 1996 (Rydstroem, 2011). Other West European countries followed suit at the end of that decade and throughout the 2000s, adopting similar but often less generous legal provisions: the Netherlands (1998), France (1999), Belgium (2000), Germany (2001), Portugal (2001), Finland (2002), Austria (2003), Luxembourg (2004), the UK (2004), Andorra (2005), Canada (2005), Switzerland (2005) and Ireland (2010). A new trend emerged in 2000, with the Dutch decision to open marriage to same-sex couples. The Netherlands was followed by Belgium in 2003, Spain in 2005, Norway and Sweden in 2009, and Iceland and Portugal in 2010. In eyes of many rights activists the recent campaign to gain legal relationship recognition represents the culmination of the LGBT movement (Waaldijk, 2000).

Table 1.2 LGBT rights by country 2011

Source: Table adapted from Bruce-Jones and Itaborahy, 2011.

* Countries that have higher legal ages of consent for same-sex sexual relations than for different-sex sexual relations....