This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Victorian soldier in Africa

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book re-examines the campaign experience of British soldiers in Africa during the period 1874-1902. It uses using a range of sources, such as letters and diaries, to allow soldiers to 'speak form themselves' about their experience of colonial warfare

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Victorian soldier in Africa by Edward Spiers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Fighting the Asante

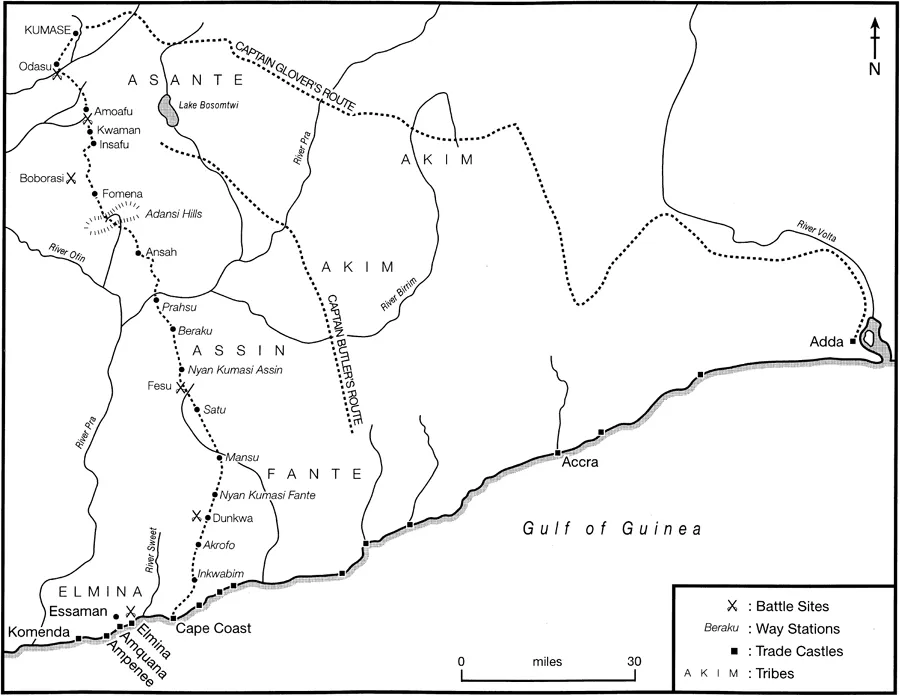

‘Wolseley’s march to Kumasi’ has been described as ‘one of the military dramas of the Victorian age’.1 Britain exercised an informal protectorate over parts of the Gold Coast from the early 1830s, the fever-ridden region traditionally known as ‘a white man’s grave’. As two previous British expeditions in 1823 and 1863–64 had suffered serious losses, the Colonial Office resolved not to send another British force to the Gold Coast, even after the Asante (pronounced Ashanti) invaded the protectorate in 1873. Although a composite force headed by a detachment of Marines under Colonel Festing thwarted the invasion at Elmina (13 June 1873), panic gripped the authorities at Cape Coast Castle.2 On 13 August the British Government appointed Sir Garnet Wolseley as administrator and commander-in-chief on the Gold Coast and despatched him, with twenty-seven special-service officers, to work with the local Fante tribesmen to resist the Asante. Following his arrival in September, Wolseley promptly requested British reinforcements, planned a short campaign over the less hazardous months of December, January and February, and then decisively defeated the Asante in battle before sacking their capital, Kumase (6 February 1874). He earned enormous plaudits for this campaign, which cost under £800,000 and involved minimal casualties.3 Yet the campaign aroused its share of controversy, both at the time and subsequently. While special correspondents, such as Henry M. Stanley and Winwoode Reade, berated the failure of his transport arrangements and the risks involved in a prompt evacuation of Kumase,4 some modern commentators argue that Wolseley discounted the military worth of the Fante precipitately.5 Few deny that Wolseley and his forces conducted a remarkable campaign, overcoming formidable natural obstacles while incurring relatively few casualties, and several commentators, taking their cue from Cardwell, regard this campaign as a vindication of his reforms.6 In reviewing the experiences of some thirty-five officers and men from all the British infantry units and support arms, it will be possible to gauge whether they had any insights on these and other aspects of the campaign.

Wolseley’s scepticism about the resolve, reliability and martial prowess of the coastal tribes, particularly if required to fight in the bush, was widely shared by British officers and men. Prior to Wolseley’s arrival in September, Colonel Festing (Royal Marine Artillery) had already engaged the Asante near the town of Elmina. With only 300 men, including light infantry, artillery, sailors and some soldiers from the 2nd West India Regiment, he had first suppressed local disaffection in the town and then repulsed an attack by some 3,000 Asantes. Having routed the Asante in about two hours, killing King Kofi Karikari’s nephew and four of his six chiefs, Festing lacked the men to mount a counter-offensive. As he said after the battle, ‘get me 5,000 native allies at Abbaye, I will undertake to engage the enemy. The native allies were promised me, but they were never forthcoming.’7 Like Festing, Wolseley quickly concluded that the Fante tribes could not protect themselves: they had become preoccupied with trading, ‘grown less warlike and more peaceful than formerly’, and their kings could not raise the men required.8 Hausas were employed in the punitive raids upon the disaffected villages of Essaman, Amquana and Ampenee, but in the raid on Essaman (14 October 1873) they were criticised for a lack of discipline and reckless firing. ‘They are plucky fellows’, wrote Lieutenant Edward Woodgate, ‘probably the best native Auxiliaries we shall get, and it is a pity there are so few of them, their great fault seems to be shyness of bush fighting, and in the difficulty of restraining them in the open when their blood is up.’9

Even when the Asantes, suffering losses from smallpox and dysentery, began their retreat to the River Pra, native forces under British command struggled to harass them effectively. Whenever the Fantes gained sight of the enemy or heard their war-drums or even a rumour of their presence, they either broke ranks and ran or cowered at the rear. Officers lamented the fate of ‘poor’ Lieutenant Eardley Wilmot, RA, who was left at the head of his column when the vast majority of native levies deserted during an action north of Dunkwa (3 November 1873). Severely wounded, he kept fighting with a small group of soldiers from the 2nd West India Regiment until shot through the heart.10 At least his courageous resistance prevented a rout, but one briefly occurred at Fesu (27 November 1873) when an advance party of Hausas, followed by the company of Kossus, broke under Asante fire and stampeded to the rear for 200 yards, carrying a naval officer ‘along in the crowd’ unable to feel his feet ‘for a long way’. ‘That affair’, he reckoned, ‘will make the Ashantees [sic] very plucky . . . they are no mean enemies in the bush. Had we had English troops it would have been different; we could have followed them into the bush, and bayoneted them, as it is not so thick here.’11 These preliminary engagements, if not tactically decisive, gave an early insight into the fighting methods of the Asante. The latter’s penchant for decapitating captured enemies prompted one ‘bluejacket’ from HMS Decoy to describe them as ‘barbarous wretches’, adding: ‘but we will give them a lesson they will not forget in a hurry. They are afraid of a white man; one is equal to four of these black fellows.’12

1 Asante War, 1873–74

Although Wolseley continued to employ native auxiliaries (two native regiments under Major Baker Russell and Colonel H. E. Wood, VC, would accompany his expedition and several others were supposed to be raised by Captains Dalrymple, Butler and Glover in diversionary columns – only one of which materialised), he requested the dispatch of British soldiers. In doing so, he accepted Cardwell’s instructions that ‘every preparation should be made in advance’, that these forces should not be disembarked until the decisive moment occurred, and that they should operate only in the most favourable climatic conditions, namely the four months from December to March.13 Originally Wolseley hoped to land these forces by mid-December, but delays created by the dilatory retreat of the Asantes, and the problems of securing and retaining the services of native labourers, delayed his plans. As the troop-ships arrived in mid-December, he sent the Himalaya carrying the 2nd Battalion, Rifle Brigade, the Tamar with the 23rd Fusiliers (Royal Welch Fusiliers) and the Sarmatian with the 42nd Highlanders (The Black Watch) back to sea until the end of the year.14

Soldiers were bitterly frustrated by the delay in disembarkation irrespective of whether they had endured a miserable journey, like Rifleman George H. Gilham, confined to his bunk for seven days, or had experienced, as Private Robert Ferguson (Black Watch) recalled, ‘a grand voyage to the Gold Coast’. Many officers and non-commissioned officers of the Black Watch were so eager to land that they offered to undertake any kind of duties ashore, but in each case they were refused.15 As in all expeditionary campaigns, the journeys from home had done much more than transport men and equipment. In the case of the Black Watch, soldiers fondly recalled the enthusiastic scenes when the Sarmatian left Portsmouth, with Prince Arthur gracing the occasion, and another salute from the Channel Squadron off Gibraltar. They forged cordial relations with the 135 volunteers from the 79th (Cameron) Highlanders, who had brought the battalion up to strength. The Camerons, who served as a distinct company, were regarded as a ‘very nice body of men . . . anxious to fall into our way of doing things’. During the voyage all soldiers were vaccinated, and they were able to prepare their equipment, attend lectures on the Gold Coast and try out their ‘drab’ Gold Coast clothing. The men were ‘rather proud’ that they were allowed to wear ‘a small red buckle fixed on their helmet’ in place of the regiment’s traditional red hackel. Although discipline had to be enforced at times (Private E. Black received twenty-five lashes for threatening to throw a sergeant overboard16), the men were in good heart when they arrived off Cape Coast, and so spending another fortnight aboard ship was remembered by Ferguson as ‘the weariest and dullest days of it’.17

Meanwhile the Royal Engineers pressed on with their labours, constructing a path along the 74 miles from Cape Coast to Prahsu, with eight camp sites, two hospitals and 237 bridges. Major Robert Home, RE, who was in charge of the task, recalled that it had to be undertaken despite recurrent tropical thunderstorms. Every day he was wet to the skin and he was eventually hospitalised with ‘a frightful attack of fever’.18 On 12 December another officer evaluated these efforts:

The engineers have pioneered the road to the Prah, hacking and hewing it through forests of teak and mahogany and across streams and swamps and over hills and valleys. Their advance will get to the Prah the day after tomorrow . . . The permanent stations for the European troops – nine [sic] in number – are nearly completed, with huts for from 400 to 2,000 men each, with officers’ quarters, hospitals, stores, magazines, and defence works. The work has never stopped, and gang after gang of labourers have been worked off their legs. This is a most exhausting service – everything to be done on foot, and I have been moving sometimes twenty to thirty miles in a day, feeling utterly done up at night, not to mention two attacks of fever, during one of which I was delirious for two days.19

The Naval Brigade, marching ahead of the main body of infantry, provided invaluable assistance. They helped t...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of maps

- General editor’s introduction

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Glossary

- Introduction

- 1 Fighting the Asante

- 2 Campaigning in southern Africa

- 3 Battling the Boers

- 4 Intervention in Egypt

- 5 Engaging the Mahdists

- 6 The Gordon relief expedition

- 7 Trekking through Bechuanaland

- 8 Reconquering the Sudan

- 9 Re-engaging the Boers

- Epilogue

- Select bibliography

- Index