![]()

1

The preferred ordeal

On the morning of the 25th October 1977 I shall be incarcerated within the confines of a concrete cell and the entrance sealed behind me. [W]ith only the basic essentials for life support and limited external contact via a microphone, my task within the eight day duration of this work will be to attempt to free myself from the isolation of these chosen limits of time and space. This will necessitate the intense activity of creating a passage from the cell, beneath the foundations of the Gallery structure, which will demand both a physical and mental extension of my present state. A journey into the unknown. (Kerry Trengove, press release for An Eight Day Passage)

But the struggle to be more fully human has already begun in the authentic struggle to transform the situation. (Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed)

The half-imagined clank of a steel pickaxe on stone sets the scene for an encounter with extremity. The year is 1977. A tunnel takes its shape through human toil. It is autumn. The performance artist’s statement of intent marks out the extremity of his own action: he will enact a feat of physical and psychological endurance by digging through concrete, brick and mortar, with the bare provisions required to survive the ordeal, across an injurious duration. It seems a kind of crossing of the Rubicon, in the name of art or of its revived and newly politicised spirit, by way of eight days of muscular transit through time and space, with the privations of the flesh that will accompany the passage. The performance is a challenge – a journey into the unknown – that cannot be revoked once commenced. Yet, moreover, the artist’s discursive and formal frames for the performance signal its broader implications, its attack of sorts on the state of art and of the social, or upon the politics of life. How may a tunnel speak? What might be achieved by the action of tunnelling that enables one’s own safe passage? If endurance-based performance might suggest the triumph of masculine subjectivity over a formidable (and usually pointless) task, how else might we read such an action? I argue that the performance of extremity in question appropriates and recasts a kind of manual labour in order to elaborate the priority of experience – and one, at that, in service of social connection and commentary – over art as a process of aesthetic and commercial production, refashioning performance on the cusp of art and life. How, so doing, does the artist – or the action – occur at a limit? What is at risk in the struggle and in the attendant endeavour to transform the situation? According to what principle may one tell the digger from the dig?

An unrepeatable performance by the British artist Kerry Trengove, An Eight Day Passage (1977) took place at the Acme Gallery, London, at 43 Shelton Street, Covent Garden. From 25 October to 1 November 1977, the gallery remained open 24 hours a day for the uninterrupted eight-day action (Figure 1.1). In its pursuit of a task-based activity over an alien duration, the Passage is an exemplary performance art action of the 1970s. It captured the imagination of contemporary audiences, local and national broadcast media and typifies a certain strand of performance art in the decade. In its duration and the intensity of its task at hand, Trengove’s extremity belongs to a compelling context of classic endurance performances, such as: Kim Jones’s Wilshire Boulevard Walk (28 January and 4 February 1976), in which he walked as ‘Mudman’, caked in clay and cluttered with homemade sculptures, from sunrise to sunset across Los Angeles’ 25 km arterial highway and again from sunset to sunrise; or William Pope.L’s Times Square Crawl (1978), the first of thirty urban crawls he has performed to date, in which he seeks to ‘crawl to remember’ the experiences of those for whom horizontality is not a choice but a fact of their destitution, from poverty, penury and placelessness (English 2007: 266); or Linda Montano’s Handcuff (1973) with Tom Marioni, in which the two artists were handcuffed together for three days, perhaps to relearn how intimacy and interdependency work in extremis.

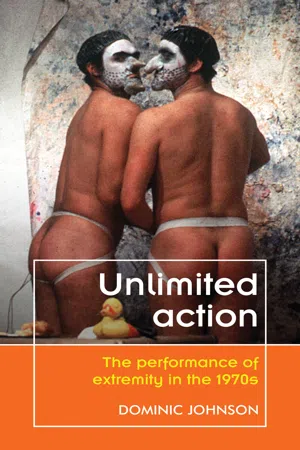

1.1 Kerry Trengove, An Eight Day Passage, photographs from a durational performance, The Acme Gallery, London, 25 October to 1 November 1977

There are a small number of critical writings on Trengove’s work from the 1970s, though he otherwise seems mostly forgotten. His work is largely not exhibited, with the exception of the inclusion of two images from the Passage in Paul Schimmel’s landmark exhibition Out of Actions: Between Performance and the Object, 1949–1979 (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1998). Published writings include a few detailed obituaries and essays published after his death on 4 September 1991, aged 45, from cancer of the tongue and throat. In an obituary, the art historian Michael Archer confirmed the significance of Trengove’s work, writing that in the context of performance art in London in the 1970s, the extremity of the Passage ‘epitomised that period’ (Archer 1991: 25). Returning the Passage to the light of day revives Trengove in his prescience, to foreground the relevance of his call to actualise, as he put it, ‘[t]hat moment in art when one is beyond reason, when instinct liberates from puritan suspicion, when vision and velocity are one’ (Trengove 1985). This work of recovery also re-establishes what Moss Madden called Trengove’s ‘reputation as an artistic brinksman’ (Madden 1991: 12), which has since been undermined or neglected. Referring to the mid-1960s, Madden writes that Trengove’s brinksmanship was inaugurated in his ‘first attempt at performance art . . . during his early days at Falmouth Art School’: in an action for which he was convicted of vandalism, Trengove ‘took a diamond ring and walked through Falmouth’s main street, scoring a line on the windows of the shops as he passed’ (ibid.). Yet he was celebrated best for a series of long durational performances in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Passage being the most iconic; after turning to sculpture and drawing around 1983, he fell into obscurity, devoting most of his energies to teaching, as well as fighting to survive several years of debilitating terminal illness.

Trengove published a series of statements to accompany the Passage, which were reproduced in a press release and advertisements for the performance and invoked in some of its extensive press coverage. A short statement by the artist is set out in broken lines like a poem:

The act, time, or right of passing.

Movement from one place to another.

A journey, a voyage, entrance or exit,

a corridor, an encounter,

an incident.1

The action of digging a hole for eight days – and his means of accounting for his project in verse – recalls both formally and politically Bertolt Brecht’s socialist redefinition of enduring acts of work as critical gestures:

Canalising a river

Grafting a fruit tree

Educating a person

Transforming a state

These are instances of fruitful criticism

And at the same time

Instances of Art. (Brecht 1987: 308–9)

Trengove liked to recite this passage: an obituary by John Roberts notes as much and reproduces the lines (Roberts 1991: 24). The poem was read in full at Trengove’s funeral in Sheffield in 1991 (alongside readings from Apollinaire, Van Gogh, Lao Tzu and Trengove’s own writings) and published in the accompanying Order of Service.2 The lines are the second and final stanza from On the Critical Attitude, Brecht’s poetic statement on the necessary rearming of criticism so as to entertain a more strident approach towards the dominant social order. As his first stanza concludes, ‘Give criticism arms / And states can be demolished by it’ (1987: 309).

Written around 1938, Brecht’s verse was published in 1963 (and translated into English in 1965) as one of The Messingkauf Poems (or Buying Brass Poems), a sequence of 38 texts that reflected on his aesthetic theories concerning the theatre. In an appendix, Brecht summarised his overarching imperative: ‘the question is whether it is at all possible to make the representation of real-life incidents the task of art, and thereby to make the spectator’s critical attitude towards those real-life incidents compatible with art’ – a challenge, he adds, that depends upon a transformation of ‘the nature of the interaction between stage and auditorium’ (Brecht 2014: 122). For Trengove, the questioning imperative holds, although he approaches the problem of a critically invested spectatorship from outside the theatrical apparatus, replacing the stage with the problem of the gallery and substituting the phenomenon of the individual spectator with dialogic environments in situ. Through Brecht – and more profoundly through the then-emergent writings of the Brazilian decolonial activist Paulo Freire – Trengove would create politically insightful performances that twinned ordeal or endurance with a new dialogical aesthetic, by prioritising, framing or extending ‘real-life incidents’ (such as digging, surviving and conversing). As such he also opposed the incipient market for the commodities that had begun to accompany performance art in the decade.

On the same press release as his staggered poem of intent, Trengove published a more substantial discursive commentary (under the heading ‘The Activity’):

Passage is essentially about the necessity and methodology of the act of creativity. [It asks] how a series of individuals, mostly unknown to each other, have each perceived, imagined, and believed in creating, an alternative future, committing their lives to making that future occur. This shared belief in the conscious extension of their own limits has been strengthened by persisting situations of extreme personal or social duress, which also divides them into two groups, those whose beliefs lead them to undertake severe experiences of their own free will, and those whose beliefs have had to be maintained through periods of excessive involuntary constraint. (Trengove, Press release; emphasis added)

Trengove is referring to a specific series of individuals, namely, former political detainees (contacted through Amnesty International) and professional athletes, whom he interviewed towards the action. He inserts his own labour into this series, by playing extracts from taped interviews with 30 detainees and 30 sportsmen, on a loop throughout the eight days of the Passage, to provide a discrete context for the activities in the upper and lower galleries (Pooley 1977). The artist Rose Garrard (his wife at the time of the action) recalls that she edited the tapes into the performance loop as ‘Kerry found it too upsetting to listen to [the recordings] again’ (Garrard 2010), suggesting the gravitas of the content of the memories recounted by the detainees. The tapes are no longer extant, but a reporter noted that one interview narrated an Argentinian political prisoner’s ordeal of being ‘kept for 40 days with his head in a canvas sack’; another speaker, a South African detainee, told of the horror of being held in solitary confinement for three years (Pooley 1977). The subjective difficulty of listening to the detainees’ stories of war, atrocity and torture would have framed, complemented and exacerbated the physical exertion and personal privation required by Trengove in the eight-day action – and arguably, though differently, for his audience. The interviews with sportspeople introduced the issue of consent, reminding audiences of the constitutive difference in Trengove’s relation to the detainees’ harrowing accounts of suffering, namely, the fact of the artist’s agency in contriving and undertaking the scene of endurance.

Trengove refers directly to the experiences of a promiscuous selection of categories of persons who undergo what he calls ‘the conscious extension of their own limits’, including both physical and psychological, self-determined and causal limits, in the course of their durational subjection to ‘severe experiences’ (Trengove, Press release). He might as well, though, be writing directly about artists such as himself, as suggested by the introductory statement concerning ‘the necessity and methodology of the act of creativity’ (ibid.). He implies the labour of voluntary training and involuntary detainment and connects this (at least implicitly) to the voluntary privations experienced in durational performance.

Despite – or precisely on account of – their palpable strangeness, difficulty and self-directed violence, Trengove’s signature actions investigated his own profound concerns about how art might enact a politics of the self or otherwise inform the central ethical and existential questions of how to live and how to act. As the art historian John Roberts writes, ‘[w]hat concerned [Trengove] was “what was it to be fully human?” given the limits currently set on human emancipation. The pursuit of extreme or constraining experiences was therefore what had to be passed through to deny these limits’ (Roberts 1992, emphasis in original), suggesting an immanent relation between intuitive difficulty – what Trengove calls the ‘moment’ (of action or location) ‘beyond reason’ – and the rupture of oppressive limits, be they political, ethical or aesthetic (Trengove 1985).

Approaching the Passage

Relics of the Passage exist today in the form of a number of photographs, short videos and archival documents. A more substantial archive for the performance – and, more emphatically, for the rest of Trengove’s work – is missing, because Trengove instructed that his archive be destroyed after his death (his first wife, Rose Garrard confirms he was ‘self-destructive to the end’); Trengove’s wish was carried out by his widow, Alison McLeod (now Radovanović), who burnt the work and scattered its ashes alongside those of her late husband in Falmouth Bay in 1992 (Garrard 2010). Radovanović confirms that the archive was destroyed in its entirety with the exception of a small number of sketchbooks or ‘highly cryptic aides de memoires rather than pictorial, analytical and/or descriptive’ (email to the author, 12 September 2015). Fortunately, a further cache of images and videos of two of Trengove’s key actions of the 1970s survive in the Acme Gallery archive.

An Eight Day Passage began at 9 a.m. on 25 October 1977, with Trengove being bricked into a section of the lower gallery. A number of printed images show the cell behind which he was imprisoned: a neat, secure structure of breezeblock and mortar, creating a cavity of around 10 × 15 ft in size, enclosed from floor to ceiling. The walls are solid, apart from a hole the size of one missing block, which acts as a viewing (and documentation) portal to the action inside it (Figure 1.2). The aperture afforded a view of Trengove’s working progress during the day or the artist resting or sleeping on his bunk if gallery-goers visited late at night. The walls are those of a prison cell, tomb or ziggurat. The tunnel is a catafalque. Inside the walled structure, Trengove lived among basic provisions, including rations of meal replacements and water, an extractor fan and a chemical toilet; and his building materials: a stack of timber boards for lining and supporting the passage, a ladder and a system with a pulley, ropes and a canvas bag for moving soil a...