eBook - ePub

The post-crisis Irish voter

Voting behaviour in the Irish 2016 general election

This is a test

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The post-crisis Irish voter

Voting behaviour in the Irish 2016 general election

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Provides the definitive study of voting behaviour in the 2016 Irish election

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The post-crisis Irish voter by Michael Marsh, David M. Farrell, Theresa Reidy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Ireland’s post-crisis election

Michael Marsh, David M. Farrell and Theresa Reidy

The 2016 general election in the Republic of Ireland was dramatic. It delivered the worst electoral outcome for the established parties in the history of the state, the most fractionalized party system in the history of the state, the greatest number of Independent (non-party) TDs (MPs) elected to parliament in the history of the state, several new political parties and groups, and was one of the most volatile elections with among the lowest of election turnouts in the state’s history. These outcomes follow a pattern seen across a number of Western Europe’s established democracies in which the ‘deep crisis’ of the Great Recession has wreaked havoc on party systems (e.g. Hernández and Kriesi, 2015). The objective of this book is to assess this most extraordinary of Irish elections both in its Irish and wider cross-national context. With contributions from leading scholars on Irish elections and parties, and using a unique dataset – the Irish National Election Study (INES) 2016 – this volume explores voting patterns at Ireland’s first post-crisis election and considers the implications for the electoral landscape and politics in Ireland.

This chapter sets the scene for the chapters that follow. We start by presenting a short background to the 2016 election, before describing the features of the 2016 INES. We then outline the key themes addressed in the book. This is followed by an overview of each of the chapters.

Background to the 2016 election

The general election was held on 26 February 2016. There were a number of legislative and political developments during the 2011–2016 Dáil (Irish parliament) term which shaped the dynamics of competition at the election. The number of seats to be filled in the thirty-second Dáil was reduced to 158 following the passage of the Electoral (Amendment) (Dáil Constituencies) Act, 2013. A commitment to reduce the number of TDs had been included in the programme for government as part of the political reform plans of the government elected in 2011. The reduction in numbers contributed to an intensification of competition for the available seats and was generally viewed to have harmed the government more than other groups (Gallagher and Marsh, 2016).

Legislative gender quotas were introduced through the Electoral (Amendment) (Political Funding) Act, 2012. The new legislation made a large proportion of state funding for political parties contingent on their running a minimum of 30 per cent of candidates of both sexes. In practice, of course, this worked as a quota for female candidates, and Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael experienced some internal tensions in their efforts to meet this obligation. Finally, new party formation was a feature of the 2011–2016 Dáil with Renua emerging as a splinter group from Fine Gael, the Social Democrats forming out of a new alignment of Independent TDs and, similarly, Independents 4 Change emerging from an alignment of former party TDs and Independent TDs, although the latter would continue to organize as a loose coalition and did not adopt the features of a political party (for more on all this see Gallagher and Marsh, 2016; Marsh, Farrell and McElroy, 2017). Independents have long been a feature of the political system and in 2016 some of this group also adapted their operating principles, with several sitting TDs and senators forming loose alliances, most notably the Independent Alliance. In sum, the election, when it was announced, was for a smaller Dáil, with more women candidates contesting than ever before and with several new party entrants to electoral competition.

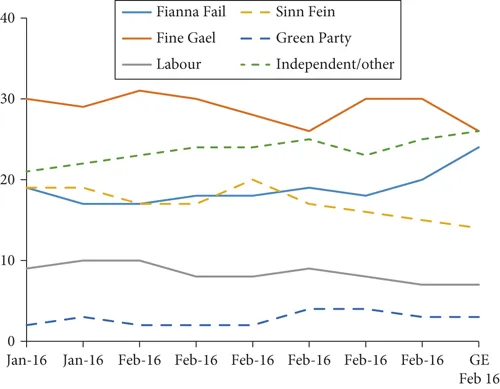

Despite speculation during the late summer of 2015 that an early election was imminent, the thirty-first Dáil saw out its full term. The Dáil was dissolved on 3 February 2016 by the Taoiseach (prime minister) Enda Kenny and the short campaign which followed was generally deemed dull and uninteresting by the attending media. Protestations of boredom aside, the campaign did matter and as can be seen from Figure 1.1, there were notable changes in the support levels for the main parties and groups during that time. Fianna Fáil and Independents trended up while Fine Gael and Sinn Féin trended down. The decline in support for Fine Gael ran contrary to a narrative in advance of the campaign that once voters engaged with important economic issues, the fortunes of the government parties would revive. The polls captured the fragmented landscape quite well and it was apparent from early in the campaign that the thirty-second Dáil would be more diverse and fragmented than ever before.

Figure 1.1 Party support levels during January and February 2016 and election result.

Source: RED C Marketing and Research (http://www.redcresearch.ie/).

Note: Dates used in Figure 1.1 do not relate to poll dates – they are time points for illustration.

The final outcome of the election is recorded in Table 1.1. Turnout was 64.5 per cent. There are a number of striking features which emerge, two of which in particular are worth noting. The combined vote share of the long-standing largest parties, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, dropped below 50 per cent for the first time. There was a sharp rise in the vote share for Independents and small parties, resulting in a fragmented electoral landscape. How and why voters delivered these outcomes is addressed throughout the chapters in this book.

Table 1.1 Results of the 2016 general election

| Party | % Vote Share | Dáil Seats |

| Fine Gael | 25.5 | 50 |

| Fianna Fáil | 24.3 | 44 |

| Sinn Féin | 13.8 | 23 |

| Labour | 6.6 | 7 |

| AAA-PBP | 3.9 | 6 |

| Social Democrats | 3.0 | 3 |

| Greens | 2.7 | 2 |

| Other | 20.2 | 23 |

Source: Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government.

AAA-PBP = Anti-Austerity Alliance – People Before Profit.

The 2016 INES

All of the analyses in this volume make extensive use of the 2016 INES. This is the fourth such study (the output of the earlier studies is presented in Marsh et al., 2008; Marsh, Farrell and McElroy, 2017). Budget limitations required a somewhat different approach to the earlier studies; accordingly, on this occasion, the INES consisted of three discrete surveys (full details of these are provided in the appendix to this volume).1 First, there was a nationwide exit poll of 4,283 voters as they left the polling station (done in conjunction with the national broadcaster, RTÉ, it was implemented by the Behaviour & Attitudes market research company). Because the exit poll was face to face, it facilitated the inclusion of a mock ballot, a crucial element in the study of voting behaviour in this most ‘candidate-centred’ of electoral systems: the single transferable vote (Farrell and McAllister, 2006). Respondents were provided with a facsimile of the ballot they had just completed moments earlier and asked to mark it as they had done. This provides us with information on the voter’s ranking of both candidates and parties. It was supplemented by questions asking voters to rate the parties, such as the standard items tapping affective orientations to parties, and questions asking respondents to rate the candidates. This provides a dataset, as with previous waves of INES, that is unusually (perhaps uniquely so) rich in terms of tapping respondents’ rating and ranking of the elements of electoral choice.

By its nature, an exit poll is time delimited to no more than about 10 minutes, which restricts how many questions can be asked. To maximize the number of questions we could ask, the respondents – all of whom had first completed the mock ballot and answered a series of core questions – were divided into three subsamples, each of which were given a different set of questions.

In order to broaden our analysis of voting behaviour in this election, we also commissioned two separate telephone polls of representative samples of Irish voters. These surveys were implemented by RED C. One of the polls applied a battery of questions from the latest wave of the influential Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) project (www.cses.org), which in this election round was focused on the theme of populism – a prominent theme in much of the analysis in this book.

In the next section, we set out the key themes of this election (some of which are particular to this election, others the culmination of tendencies that started earlier) that guide the analysis to follow in the remaining chapters.

Key themes

The objective of the book is to provide a comprehensive understanding of voter decision making in Ireland while also assessing some of the theoretical propositions that currently dominate debates on elections in established democracies. From an Irish perspective, six propositions drawn from the international literature are particularly pertinent: changing partisan identities, issue mobilization, new ideological dimensions of politics, party system change, populism and generational effects. Structuring the analysis along these lines facilitates both a deep analysis of the 2016 election and the location of the Irish experience in a cross-national perspective.

Changing partisan identities: Partisanship has long been low in Ireland by international standards, yet elections have tended to produce relatively stable outcomes over many decades. The year 2016 was an especially volatile election and the final result raises interesting questions about party attachment. As we have noted, several new parties emerged between 2011 and 2016; their capacity to establish enduring partisan ties will be important for their long-term prospects. The reversal of Fianna Fáil’s decline and the consolidation of Sinn Féin support hint at changing partisan identities, certainly in the latter case. The relationship between voters and parties is addressed across chapters 2, 5, 7, 9 and 10.

Issue mobilization: A number of controversial policies were introduced during the 2011–2016 parliamentary term, most notably water charges, which prompted huge protests across the state and a widespread refusal to pay (leading to a decision by the government elected in 2016 to abolish the charges). The high-profile marriage equality referendum in 2015 led to a surge in voter registration and turnout jumped sharply from previous referendums (Elkink et al., 2017). Taken in the round, it is clear that issues have the capacity to mobilize voters, and how these types of issues manifested at the 2016 election will be considered across chapters 3, 5, 7, 8 and 10.

Ideological dimensions: Voters in many established democracies are increasingly distrustful of, and indeed angry at, politicians and political parties. This situation is sometimes attributed to economic uncertainty and vulnerability caused by hyper-globalization, the idea being that globalization has created a different set of economic winners and losers and so has activated a new and enduring political cleavage. A social dimension has also been mooted, one that suggests voter attitudes can increas...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures and tables

- Notes on contributors

- Editors’ preface

- 1 Ireland’s post-crisis election

- 2 Mining the ballot: Preferences and transfers in the 2016 election

- 3 Ideological dimensions in the 2016 elections

- 4 Social and ideological bases of voting

- 5 Party identification in the wake of the crisis: A nascent realignment?

- 6 Why did the ‘recovery’ fail to return the government?

- 7 Party or candidate?

- 8 Political fragmentation on the march: Campaign effects in 2016

- 9 The impact of gender quotas on voting behaviour in 2016

- 10 What do Irish voters want from and think of their politicians?

- 11 Popularity and performance? Leader effects in the 2016 election

- Appendix

- Index