The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes

In 1661, the twenty-three-year-old Louis XIV (1638–1715) took full command of his country, which he was to rule for over half a century.2 The new King was no diplomat and devoted most of his reign to fighting neighbouring nations. As a staunch Catholic seeking to reinforce France’s independence, Louis decided to sever his kingdom from foreign influences and unify it around a single religion, his own.3 Whilst his grandfather Henry IV’s Edict of Nantes had granted toleration to French Protestants in 1598, Louis presumptuously believed he could achieve a stronger unity by eradicating them: ‘Mon grand-père aimait les Huguenots et ne les craignait pas; mon père ne les aimait point, et les craignait; moi je ne les aime, ni ne les crains.’4 Of his twenty million subjects, fewer than a million were Protestants; they formed a declining minority, mostly concentrated in Normandy and the south, with one-quarter of them – 200,000 according to contemporary accounts – in Languedoc.5 Except for Rohan’s wars (1620–29) and the Siege of la Rochelle (1628), the Edict of Nantes had somewhat tamed the dispersed Huguenot nobility, who no longer represented a cohesive force by the mid-seventeenth century.6 The recent agitation of the Fronde still prompted Louis to tighten his grip on the Huguenots despite their loyalty toward the new King. He increased the fiscal exploitation of Languedoc’s booming economy, based on a solid textile industry, and on maize and wine production, to fulfil his absolutist aspirations.7 Such brutal bias fuelled tensions between obedient Calvinists and ruling papists, who respectively understood Catholicism as a synonym for tyranny and Protestantism as another word for sedition.

The coercion of the Huguenots unfolded progressively over a quarter of a century. Between 1661 and 1679, a strict reading of the Edict of Nantes combined with fiscal and financial incentives first sought to make Catholicism a more advantageous religion.8 This led to the destruction of thirty-five temples in Languedoc, where the authorities concentrated their efforts. From 1679 onward, decrees were issued further revoking the guarantees that Protestants had obtained in 1598.9 For example, they could no longer work in the civil service, occupy a position of power, or practise medicine.10 Mixed courts, composed of an equal number of Catholic and Protestant jurors, were also banned. Children had to convert from the age of seven, which in practice meant that any child found playing on the street or in an open garden could be taken by force to be raised in a Catholic institution at his parents’ expense, a practice that was far from exceptional:11 ‘The Clergy shut up in Convents and Seminaries all their Children of both Sexes, in order to instruct them in their Religion; hoping by that Means, that when the Old People were dead, the Protestant Religion in France would be at an End.’12 The year 1681 marked the beginning of the notorious dragonnades, decentralised military campaigns instigated by provincial intendants to crush civil resistance throughout southern France. Dragoons were billeted in Protestant homes, their costs to be covered by the occupied families.13 Facing death threats, the Huguenots’ conversion followed the dragoons from west to east, from the Béarn area to the safe Protestant haven of Montauban and finally Languedoc. Montpellier converted on 29 September 1685, followed by neighbouring towns and villages of the Cévennes: Anduze (7 October); Saint-Jean-du-Gard (8 October); Sauve, Saint-Hyppolyte-du-Fort and Ganges (11 October); and Barre (12 October).14 Restrictions multiplied to such an extent that Louis no longer saw any point in protecting a minority now numerically insignificant. On 18 October 1685, he signed the Edict of Fontainebleau to repeal that of Nantes, ostensibly because so many of his subjects had abjured their ‘so-called Reformed religion’ to embrace Catholicism.15

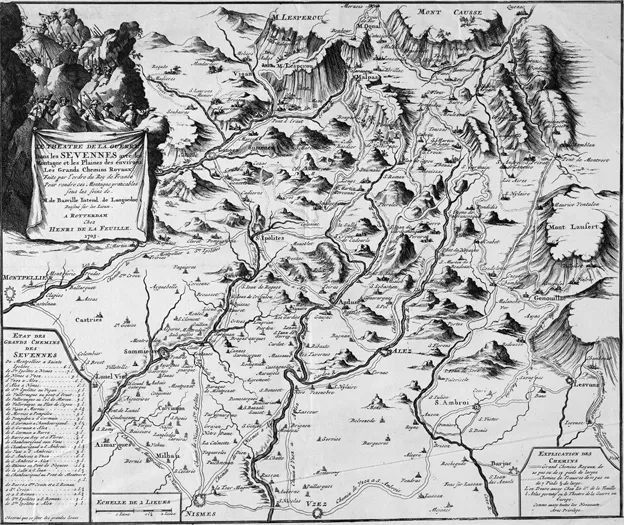

The intensity of the dragonnades in Languedoc was anything but incidental, for this province occupied a peculiar place in France, both geographically and historically. Under Louis XIV, it was the largest in the kingdom, considerably larger than it is today: from west to east it spanned from its Catholic capital Toulouse to the Rhône River, and north to south from the Massif Central down to Narbonne, on the Mediterranean coast (see Figure 1). It consisted of the County of Toulouse and the provinces of Quercy, Rouergue, Gévaudan, Vivarais and Velay. This large territory had for a long time enjoyed political autonomy and was strategically important, as it offered access to the sea and the Pyrenees to secure French borders from Spain.

The Cévennes mountains, north of Montpellier, stood out for their distinctive topography and identity. This rugged area abounded with forests, caves, gullies and remote villages, and was regularly cut off from the outside world by cold winters and snows between October and March. Villagers often had two occupations to cope with the seasons; shepherds and peasants in springtime and summertime; and carders and weavers for the rest of the year. They sold their wool down in the valley, in Mende, to be exported to Germany, Italy, Spain and Turkey, although bed-linen and silk were the most important manufactures of the area.16 Communication with the outside world depended heavily on trade, but both were limited by seasonal conditions. The lack of roads connecting the villages of the Cévennes to the surrounding towns of Montpellier, Nîmes or Mende meant that people simply relied on goat paths and a thorough knowledge of the terrain.

Unlike mainstream Huguenots – a disproportionately urban population of artisans, merchants, soldiers and bankers with a higher literacy rate – the Cévenols were a distinctively poorer, rural population and lived in a particularly austere environment.17 This partly secluded rural population was also confronted with a language barrier. Seventeenth-century France remained linguistically divided: although French had become the official language in 1539 under Francis I (1494–1547), it was mostly spoken north of the Loire Valley and in southern towns, whilst rural areas kept their dialects.18 Beside hindering the spread of popular literacy, since books and official records were published in French, this also meant in practice that the authorities in Montpellier still ...