![]()

1

The will of the universe

The cosmic voyage

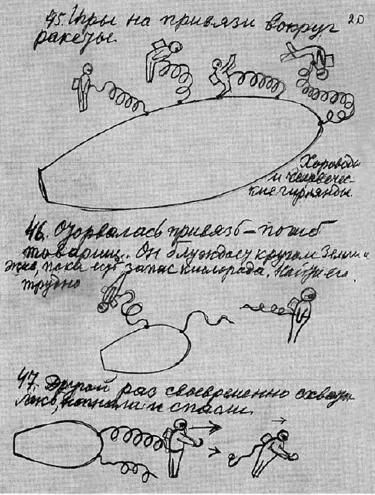

A group of cosmonauts float in outer space, tethered to their spaceship, in a series of crudely rendered sketches. The handwriting accompanying the sketch, the first of three on a page (Figure 1.1), explains that life in space involves “playing games around the spaceship,” and forming “human garlands.” In the two sketches beneath the garland, play is replaced by celestial drama. The hose connecting one cosmonaut breaks and his body drifts away from the ship. He is dead, the note explains. But in the third scene, an arrow points from the eyes and hands of a tethered cosmonaut toward the one floating in space. In an alternative scenario, the explanation tells us, a fellow cosmonaut reacts in a timely manner to the mishap and manages to save his “comrade.”

These numbered sketches are part of a series of drawings from the notebook of the scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, prepared for the film Cosmic Voyage. In addition to presenting in his drawings cosmic pleasures, perils, and camaraderie, Tsiolkovsky also laid the foundations for Russian space travel. At least half a century before the Soviet Union launched its cosmonauts, he produced technical inventions that made Russian victories in the Space Race possible. Over the course of fifty years, from the end of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth, Tsiolkovsky developed visions of life in the universe and calculated ways to attain that life. He had survived the tsarist regime, witnessed the Revolution of 1917, lived during the era of Lenin's New Economic Policy of the 1920s, and finally seen the beginning of Stalin's Five-Year Plans, all the while spending most of his time in the little village of Kaluga, 200 kilometres from Moscow. In his teens, during a three-year stay in Moscow, he learned mathematics, physics, astronomy, and chemistry from books borrowed from public libraries.1 The other source of his self-education was the work of Jules Verne. Relying on textbooks and Verne, this visionary created a mathematical model of liquid-propelled rockets, without which the Soviet space programme of the 1960s would have been impossible. Tsiolkovsky, a scientific amateur by common standards, operated from a homemade lab, and during the tsarist era supported himself by writing popular science for members of amateur space travel societies. During the Stalinist period, several years before his death, he finally received official recognition as a national hero.

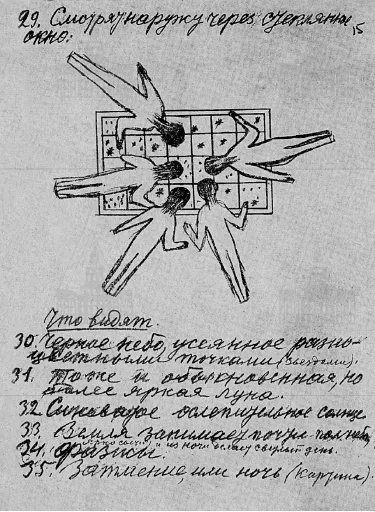

Tsiolkovsky wanted to provide a comprehensive design for the space mission. He designed the first working rockets, but also items such as picture windows through which, as one of his sketches shows, naked women floating in space could look at the stars (Figure 1.2). He provided not just the know-how for launching a rocket into space, but also a body of metaphysical thought to accompany it. For Tsiolkovsky, everything that exists is driven by an entity he calls “the will of the universe.” In a book with this phrase as its title, he explains the purpose of his life's work.2 Human history, he proposes, is part of a trans-human evolution of the cosmos, driven by a transcendental power that is not absolute and immutable but evolves as it drives history. Today, this power, “the will of the universe,” reveals itself “as the will of an unreasonable being.”3 Since the transcendental power in the world is still irrational, Tsiolkovsky writes,

we see the mixture of sensible and stupid, kind and cruel in the affairs of the earth and mankind. What is the sense of poverty, diseases, prisons, malice, wars, death, stupidity, ignorance, narrow-mindedness of science, earthquakes, hurricanes, bad harvests, droughts, floods, vermin, ferocious animals, bad climate, etc?.4

But humankind evolves together with the cosmic will, toward greater perfection, toward self-empowerment, toward a “glorious state.”5 It will reach this state when it starts exploring the solar system or moves to some other system in the Milky Way and finds that single planet in which are “more favorable conditions for the development of higher intelligence.” As the “will” evolves, humankind conquers the “Ether” and “liquidates painlessly everything imperfect, populating planets with a perfect generation.”6

In 1928, the year The Will of the Universe was published, the era of Stalin's Five-Year Plans began. In this context, Tsiolkovsky's reasoning about the nature of human progress and the celestial destination of the human race fits into the communist master narrative. It matches the teaching that first there is socialism, an evolutionary stage on the path toward the end of history, and communism is this history's end, a perfect classless and stateless society in which the imperfections of the human race and the “mixture of sensible and stupid, kind and cruel” will finally vanish. Tsiolkovsky's work on situating communism in outer space and presenting the path toward life in it as the manifestation of a cosmic will in many ways lends the communist master-narrative a transcendental dimension, and presents the course of Soviet history as part of cosmic evolution.

Tsiolkovsky's celestial utopia is situated in outer space – the metaphysical milieu of the cosmic void. To picture this void, to invent the means for reaching it, means not only to design an alternative reality, but also to speculate about the ends of human existence and the meaning of history. What does this mean in the context of socialist speculation? What form does a celestial utopia take when a religious interpretation of the heavens is replaced with a socialist one? How did projects such as Tsiolkovsky's, or, as later chapters explore, projects which pair the realistic with the fantastic, the far-reaching vision with the ridiculous, articulate the metaphysics of communism? How do the instigators of such projects speak about history or about the ends of communism as the radical modernist effort to transform the world? A good way to begin considering answers to these questions is to look precisely at the tradition of cosmic and celestial utopias – the most literal version of communist metaphysics – from their origins in pre-Revolutionary science and fiction and up to their concluding chapter at the end of Soviet history.

Communism and the Martians

The work of the rocket engineer and designer of “human garlands” belongs to the cosmist movement, which emerged in the decades before the October Revolution and was based on the work of late nineteenth-century theologian Nikolay Fedorov. Fedorov promoted the idea that the “common mission” of mankind was eternal life and the conquest of space. People inspired by Fedorov claimed that fundamental human rights included the right to eternal life and the right to interplanetary travel, both of which demanded liberation from capitalism. In addition to Tsiolkovsky, members of this group included such influential figures as Leonid Krasin, the designer of the Lenin Mausoleum, and Valerian Muravev, a writer and philosopher, one of the managers of the Central Institute of Labour founded to improve production efficiency. Writing about training factory workers in the Central Institute of Labour, Muravev combined ideas about efficient production with ideas about immortality. Like the director of the Institute, Aleksey Gastev, whose work will be discussed in Chapter 2, Muravev believed that the rhythm of factory work has to be synchronized with that of the cosmos; at that point the proletariat will eliminate the earthly notion of time and begin to live in the celestial eternal present.

The most popular pre-Revolutionary book that presents revolutionary life as celestial life is Alexander Bogdanov's Red Star, published in 1908. Bogdanov, one of the founders of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party from which the Bolsheviks and the Soviet Communist Party descended, decided to popularize the proletarian struggle. So he wrote an adventure story in which the protagonist travels to the ideal communist society in space. Martians, led by an undercover agent named Menni, select the hero of the story, Leonid, a member of the Russian Socialist Democratic Party, to visit Mars so he can report back to the humans about what he learns. He travels via an “etheroneph” powered by “antimatter” and observes daily life on the Red Planet. He sees factories in which workers indulge in fulfilling labour and are free to change professions; fantastic glass-clad domestic architecture; progressive ways of childrearing; free love; and art museums transformed from sites for collection and accumulation into places for study. By experiencing everyday life in a Martian society, Leonid gets a picture of what his political struggle on Earth will bring about.

In one scene in the n...