This is a test

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

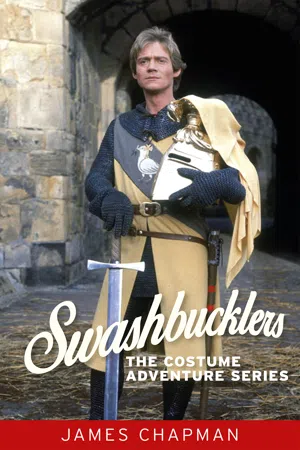

Swashbucklers is the first study of one of the most popular and enduring genres in television history – the costume adventure series. It maps the history of swashbuckling television from its origins in the 1950s to the present. It places the various series in their historical and institutional contexts and also analyses how the form and style of the genre has changed over time. And it includes case studies of major swashbuckling series including The Adventures of Robin Hood, The Buccaneers, Ivanhoe, William Tell, Zorro, Arthur of the Britons, Dick Turpin, Robin of Sherwood, Sharpe, Hornblower, The Count of Monte Cristo and the recent BBC co-production of The Three Musketeers.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Swashbucklers by James Chapman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism for Women Authors. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Exporting Englishness

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1955–60) marks the origin of the television swashbuckler. Its history is inextricably linked to the early history of the ITV network in Britain: its first episode, broadcast in the London region at 5.30 p.m. on Sunday 25 September 1955, was one of the highlights of ITV’s opening weekend. It was an immediate popular success, not only in Britain, where it regularly featured among the top-ten shows, but also in the United States where it was bought by the national CBS network. The Adventures of Robin Hood remained in production for four years and ran for 143 half-hour episodes. It was repeated with such frequency that in the late 1950s and early 1960s it was hardly ever off the airwaves in Britain. Now fondly remembered for its catchy theme song (which became a top-twenty hit for David James in 1956) and for its repertory company of stalwart British character actors in sackcloth costumes, sporting bad wigs and even worse ‘yokel’ accents, The Adventures of Robin Hood has recently attracted critical interest due to the involvement of a number of blacklisted American writers whose contributions had a significant bearing on the politics of the series.1 The semi-American parentage of The Adventures of Robin Hood, moreover, raises important questions about the economic and cultural capital of this representation of perhaps the most quintessentially English of all popular folk heroes.

The political economy of The Adventures of Robin Hood

Steve Neale has argued that The Adventures of Robin Hood ‘was transnational in origin and appeal and in financial and institutional terms from the very outset’.2 In order to contextualise the series it is necessary to consider it in relation to the production strategies of both British and American commercial television in the mid-1950s. The Adventures of Robin Hood was produced by Sapphire Films for the Incorporated Television Programme Company (ITP), a subsidiary of Associated Television (ATV), one of the regional franchise operators in the ITV network which broadcast in London on weekends and in the Midlands during the week. The advent of the ITV network as a commercial rival to the monopoly of the BBC had come about through a range of factors including, but not limited to, the election in 1951 of a Conservative government that supported the principle of competition, an orchestrated campaign by theatre managers and talent agencies who wanted more television exposure for their artistes, and the building of new television transmitters, which meant that by 1953 all but the remotest parts of the United Kingdom could receive television signals.3 ITV was derided by its critics as representing the worst kind of commercial enterprise and for pandering to the lowest common denominator in taste. For its supporters, however, ITV marked the triumph of populism and consumer choice. ‘So far,’ declared the first TV Times editorial, ‘television in this country has been a monopoly, restricted by limited finance, and often, or so it seems, restricted by a lofty attitude towards the wishes of viewers by those in control’. ITV, in contrast, aimed ‘at giving viewers what viewers want – at the times viewers want it’.4

The Adventures of Robin Hood exemplifies two separate, though related, processes in the television industry during the 1950s: the rise of international co-production-distribution arrangements and the move into telefilm series production. Most accounts of The Adventures of Robin Hood tend to see it as exceptional: the first British series sold to a US network.5 Lew Grade, the flamboyant, cigar-smoking theatrical agent, was one of the driving forces behind the formation of independent television in Britain: Grade was both managing-director of ITP and deputy managing-director of ATV (later becoming its managing-director in 1962). In his autobiography Grade claimed that he committed £390,000 of ITP’s original capital of £500,000 to the production of the first series of The Adventures of Robin Hood and that it ‘grossed millions of pounds’.6

Although it was undoubtedly the most successful example of its kind, The Adventures of Robin Hood was by no means unique. Sapphire Films was just one of several producers at the time making telefilm series for ITV but with a view also to international sales: others active in the mid- and late 1950s included Towers of London (whose managing-director, Harry Alan Towers, was a shareholder and board member of both ITP and ATV), Danziger Productions (run by American brothers Edward J. and Harry Lee Danziger) and George King Productions (King had been a prolific director of ‘quota quickies’ in the 1930s, who moved into television in the 1950s). Towers produced The Adventures of the Scarlet Pimpernel (1955), another costume adventure series that aired during ITV’s first week, while the Danzigers, specialists in low-budget crime films, turned their hands to television with Mark Saber (1954–55) and The Man from Interpol (1959–60).7 While the funding arrangements varied, the usual model was for a series to be made in association with an American partner who would provide ‘end money’ in return for the lucrative US distribution rights. The Adventures of Robin Hood was produced in association with Official Films: ITP distributed it in the western hemisphere and Official Films in the eastern hemisphere. Official Films was one of several companies specialising in selling telefilm series in the United States: others included National Telefilm Associates and Screen Gems (a television subsidiary of Columbia Pictures).

The involvement of American co-production partners in British television reflected a trend in the film industry during the 1950s. As part of the move towards so-called ‘runaway’ productions, Hollywood studios became increasingly involved in British-based production to the extent that some, such as MGM, even opened their own British production facilities. There were several reasons for this trend: cheaper production costs, especially following the devaluation of Sterling in 1949; the limitation on dollar remittances imposed by the Treasury which meant that US distributors had ‘frozen funds’ in Britain; and eligibility for a subsidy from the British Film Production Fund (commonly known as the Eady Levy, introduced in 1951), provided that the films were produced by a nominally British company using British studio facilities and with three-quarters of the labour costs paid to British workers.8 At this time Britain was still the most lucrative overseas market for American films and largely as a consequence of this a large proportion of ‘Hollywood British’ films were on British subjects, including costume films and swashbucklers. MGM, for example, produced a cycle of three chivalric epics – Ivanhoe (1952), Knights of the Round Table (1953) and The Adventures of Quentin Durward (1955) – while other studios producing swashbucklers were Warner Bros. (Captain Horatio Hornblower RN, 1950; The Master of Ballantrae, 1953; King Richard and the Crusaders, 1954), Columbia (The Black Knight, 1954), Twentieth Century-Fox (Prince Valiant, 1954), Universal-International (The Black Shield of Falworth, 1954) and Walt Disney (The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men, 1952; Rob Roy, the Highland Rogue, 1953; Kidnapped, 1959). Disney’s Robin Hood film, starring Richard Todd and directed by Ken Annakin, was to a large extent the template for The Adventures of Robin Hood.9

The reasons for US investment in telefilm production in Britain were very similar to those which attracted Hollywood to British shores. Variety observed that ‘sound and obvious economic reasons’ lay behind the growth of Anglo-American production partnerships.10 For the British producer a US partner significantly increased the likelihood of US sales, either to a network (which guaranteed a fast return on the initial investment) or through syndication (where, as Variety put it, the British partners ‘have to wait much longer before they can share in the American gravy’). The network sale of The Adventures of Robin Hood meant that ‘the British company not only acquired desperately needed product for its own use, but also hit the jackpot with their quick US return’.11 At the same time British production was attractive to American partners because costs were on average 20 per cent lower in Britain and because this British-made product gave them a foothold in the British television market. The British commercial companies, regulated by the Independent Television Authority (ITA), had agreed to impose a quota of imported television (no more than seven hours a week) in response to concerns over the ‘Americanisation’ of British airwaves. (This policy was similar to the film industry, where the Cinematograph Films Act of 1927 set a minimum quota of British films for distributors and exhibitors. The distributors’ quota was abolished in 1948.) A television series shot in Britain with a predominantly British cast and crew qualified, like its film counterparts, as a British production rather than an import.12

The Adventures of Robin Hood also exemplified the shift towards telefilm production in the 1950s. Until the advent of magnetic videotape and the introduction of Ampex video machines in the late 1950s, there were two options for television drama: live performance in the studio or shooting on film. The former was the preferred mode of production during the early years of television for a combination of economic and aesthetic reasons: it was cheaper than film and it led to the emergence of a distinctively televisual style that differentiated the new medium from cinema. Early live television drama was characterised by an aesthetic of intimacy and immediacy that privileged interiors and close ups and thus encouraged intense, character-focused psychologically oriented narratives. Thus it was that the ‘golden age’ of US television drama in the 1950s was notable for the production of social realist television plays by writers such as Paddy Chayefsky (Marty), Rod Serling (Requiem for a Heavyweight) and J. P. Miller (Days of Wine and Roses). Yet this golden age was short lived, as telefilm production was already on the increase by the mid-1950s. This process coincided with the relocation of US television production from New York to Hollywood and with the increase in the number of television stations in America after 1952 when the Federal Communications Commission lifted its freeze on the issue of new licences. The rapid rise in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Exporting Englishness

- 2 Fantasy factories

- 3 Revisionist revivals

- 4 Rebels with a cause

- 5 Heritage heroes

- 6 Millennial mavericks

- Conclusion

- Select bibliography

- Index