This is a test

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

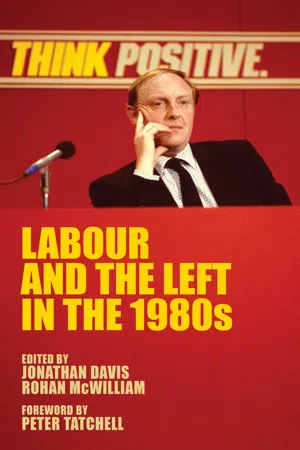

Labour and the left in the 1980s

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume, the first scholarly study of Labour and the left in the age of Michael Foot and Neil Kinnock, opens up a whole new area of historical inquiry, and demonstrates why the 1980s political inheritance has become timely once more.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Labour and the left in the 1980s by Jonathan Davis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia británica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The crisis of the Labour Party

1

Retrieving or re-imagining the past? The case of ‘Old Labour’, 1979–94

God doth know, so shall the world perceive,

That I have turned away from my former self.

(Henry 1V Part Two, Act 5, Scene 5)

Our fundamental tactic of self-protection, self-control, and self-definition is … telling stories, and more particularly concocting and controlling the story we tell others – and ourselves – about who we are.1

For Blair, ‘Old Labour’ was ‘like a restaurant that poisoned its guests … Think of that restaurant. If you had come home after what you thought was a good meal and had been violently ill for a week, what would make you return?’2

He who controls the past controls the future. He who controls the present controls the past.3

The origins and meaning of ‘Old Labour’

This chapter argues that the concept of ‘Old Labour’ was essentially a strategic device. Coined in the 1990s by a group within the party, known initially as ‘the modernisers’ and subsequently as ‘New Labour’, it was used to refer to the party as it existed prior to Tony Blair's assumption of the leadership in 1994.4 The concept was widely employed, both inside and outside Labour's ranks, and structured public discourse about the party to such a degree that, as the Independent put it, it became ‘an effortless part of our vocabulary’.5 As we shall see, it operated as the central organising concept of a larger, more encompassing narrative which creatively reimagined the party's past in a way that facilitated the New Labour ‘project’.

Eric Hobsbawm explains: ‘What is officially defined as the “past” clearly is and must be a particular selection from the infinity of what is remembered or capable of being remembered.’6 Not surprisingly, Labour's history has lent itself to a wide range of such definitions, but these represent scholarly divergences, grounded in evidence and logical reasoning and, hence, legitimately differing versions of the past.7 The view promulgated by the ‘modernisers’ amounted to something quite different: not a scholarly contribution but a strategic and rhetorical intervention designed to secure behavioural change by reshaping the popular image of the party.

The significance of the craft of persuasive communication is now widely recognised. Its point of departure is the gap between the social world as it objectively exists and as it is subjectively apprehended. Events in the wider world do not manifest themselves as ‘pre-existent entities’ whose meaning ‘can be read straight from reality’.8 In order for the raw material of existence to be transmuted into something intelligible, meaning has to be assigned. This applies, in particular, to the political world, where myriad events, mostly outside people's direct experience and frequently of little concern to them, swirl around in a kaleidoscope of bewildering patterns.

Inevitably, in a world of competitive politics, rival political camps seek to mobilise support by gaining assent for their slant on events. Blumler has described this as ‘the modern publicity process’; that is, the ‘competitive struggle to influence and control popular perceptions of key political events and issues through the mass media’. In this intensely fought struggle what counts is ‘getting the appearance of things right’.9 Two techniques increasingly deployed by party communicators to achieve this are the use of narratives and framing devices. A narrative ‘refers to the ways in which we construct disparate facts in our own worlds and weave them together cognitively in order to make sense of our reality’.10 It helps to organise and steer our understanding of the endless succession of events and messages that relentlessly bombard us. Those who devise and disseminate them have two main purposes: firstly, to supply a conceptual vocabulary to structure the target audience's understanding of the social world and, secondly, by helping to shape these understandings, to affect their behaviour in such a way as to serve the narrators’ purposes.11 This process of narrative dissemination we call framing. A frame highlights for public consumption the salient features from an otherwise baffling multitude of events, organising them in such a way that the frame offers both a diagnosis of what is wrong and a prescription of how this can be repaired.12 Framing lies at the core of persuasive communication, as it seeks to ‘assign meaning to and interpret relevant events and conditions in ways that are intended to mobilise potential adherents, to garner bystander support, and to demobilise antagonists’.13

The problem for Labour, as the modernising group which emerged in the late 1980s (for example, Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, Peter Mandelson, Philip Gould) understood, was that the frame of reference via which most voters viewed the Labour Party was unremittingly grim. Focus group research in the mid-1980s indicated that, for most voters, the party was identified with positions on such matters as welfare, gender and race that were (in Philip Gould's words) ‘beyond what ordinary, decent voters considered reasonable and sensible’.14 The party was seen as in thrall to trade union ‘barons’, riven by factionalism and prone to extremism. In the vivid words of the modernisers’ principal strategist, Philip Gould:

To millions of voters Labour became a shiver of fear in the night, something unsafe, buried deep in the psyche, not just for the 1983 election campaign or the period immediately after it but for years to come. Like a freeze-frame in a video, Labour's negative identity became locked in time.15

In Lewis Minkin's evocative phrase this constituted ‘the burden of history’.16 The proposition at the core of New Labour's strategic thinking was that Labour as a brand was so sullied that it was beyond redemption. As Philip Gould put it, ‘Labour had to modernize completely or eventually it would die’.17 The voters would regain trust in Labour's capacity to govern, and to govern in their interests, only if they were convinced that a surgical break with the past had occurred. The senior New Labour advisor, Matthew Taylor, recalled that, following the ‘gut wrenching defeat in 1992’, party modernisers ‘took it as read that Labour could not be elected unless they had completely eradicated any connection to the discredited party of the winter of discontent [of 1978–79] and the 1983 manifesto’.18

One response may have been to attempt to dislodge, or at least dilute these perceptions as unfair, inaccurate and one sided. But this was not the approach taken (or even seriously contemplated) by the modernisers after 1992, and for three main reasons. Firstly, they believed that these perceptions were, if perhaps a little exaggerated, largely correct. Secondly, they calculated that it would be conducive to the success of the ‘New Labour Project’ if party members could be induced to accept that they were indeed correct. Thirdly, they were convinced that popular attitudes were so...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Notes on contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction: new histories of Labour and the left in the 1980s

- Part I: The crisis of the Labour Party

- Part II: The British left in a global context

- Part III: Currents of the wider left

- Index