This is a test

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The first monographic study of the painter Agostino Brunias, this book offers a compelling, original analysis of his representation of race in the British colonial West Indies, reconsidering the way in which the artist's oeuvre has previously been understood.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Colouring the Caribbean by Mia L. Bagneris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Brunias’s tarred brush, or painting Indians black: race-ing the Carib divide

In 2002 the government of St Vincent proclaimed the eighteenth-century Carib warrior Chatoyer a national hero. A chief among the so-called ‘Black’ Caribs, Chatoyer led valiant campaigns against British colonial forces during the two Carib Wars (1772–73 and 1794–98) that were the dramatic culmination of the Carib/British colonial contest. Recently, the hero’s bold image has emerged as an emblem of local pride – reproduced in promotional tourist literature, adorning the covers of recuperative histories of the Black Carib people,1 and even featured on the front of a popular phone card. Chatoyer has come to embody resistance against colonial oppression in the collective memory of the Vincentian people and among those who identify as Black Caribs in particular.2 Ironically, however, the artist who recorded the likeness by which modern-day Black Caribs venerate Chatoyer as a national hero was, in fact, employed by the very oppressors that the Carib leader and his people so fiercely resisted.

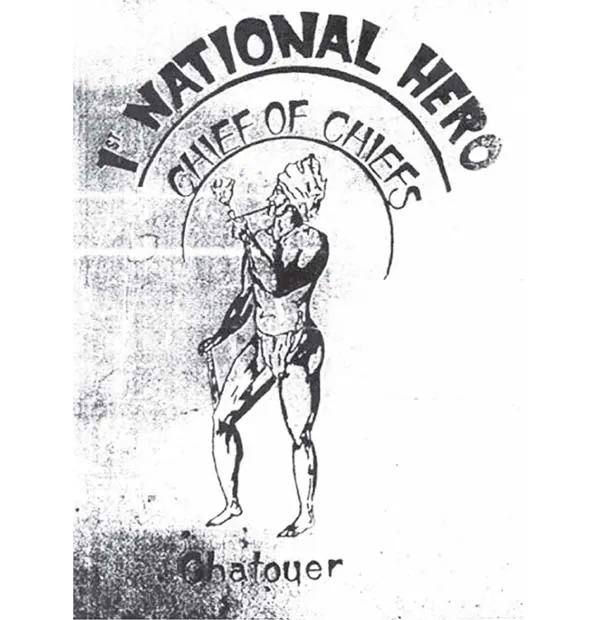

In a recent popular culture image (fig. 4) Chatoyer, clad in loincloth and headwrap, stands in heroic profile smoking a long pipe. Despite the absence of solid ground beneath him, his strong stance makes his muscular legs appear firmly rooted, rendering the stick upon which he rests his hand more a symbol of authority than a source of support. Declarations printed in underscored arcs radiate from the warrior’s head, proclaiming him the ‘Chief of Chiefs’ and St Vincent’s ‘1st National Hero’. This iconic depiction represents the hero remembered with pride by those who identify as Black Caribs today. However, cropped from the original context, the iconic Chatoyer tells only part of the story.

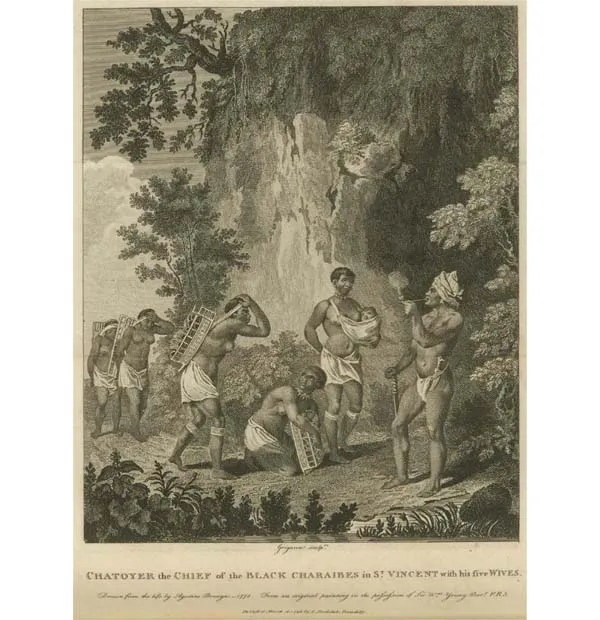

The original source of the figure, Agostino Brunias’s Chatoyer the Chief of the Black Charaibes in St. Vincent with his Five Wives (fig. 5; hereafter Chatoyer with his Five Wives), circulated widely through an engraving by Charles Grignon that appeared in Bryan Edwards’s epic colonialist tome The history, civil and commercial, of the British colonies in the West Indies.3 In this picture, the same pipe-smoking Chatoyer from the ‘Chief of Chiefs’ image supervises a procession of five female Black Caribs as they progress along a path amidst a densely wooded landscape. The three women at the rear of the line stoop under the weight of their heavy loads, carried in the traditional Carib manner in woven pegals.4 Paused in front of them, the second in the procession bends over the fallen load at her knees, repacking her carrier, while the leader of the female party, wearing a baby slung in a fabric carrier across her breast, stands at the front. She faces her husband, the bent knees of her pose echoing his own. Rather than portraying Chatoyer as the leader of an army of fearless Black Carib warriors, Brunias shows him as the tyrannical overseer of an army of ill-treated wives in an image that highlights the polygamy of the Black Caribs and the drudge-like treatment of their women that Britons, rather hypocritically given the rampant sexual abuse of enslaved women by British colonists, found abhorrent.5

4 Unknown artist, 1st National Hero, Chief of Chiefs, c. 2000

Despite the less-than-flattering light in which Chatoyer with his Five Wives depicts the ‘1st National Hero’, there can be little doubt as to why those seeking to recuperate Black Carib history and pride found it a more apt source than the alternative. The other visual work for which Chatoyer reputedly was an original model, Brunias’s Treaty between the British and the Black Caribs* (fig. 6), commemorates the adoption of the treaty that concluded the First Carib War.6 Showing a delegation of scantily clad Black Caribs who have cast their weapons on the ground at their feet, the scene specifically illustrates the provision of the treaty in which they agree to ‘acknowledge his Majesty [King George III] to be the rightful sovereign of the island … take an oath of fidelity to him as their King; promise absolute submission to his will, and lay down their arms’.7

5 Charles Grignon after Agostino Brunias, Chatoyer the Chief of the Black Caribs in St. Vincent with his Five Wives, 1801

Chatoyer, a few inches taller than his Black Carib brothers, stands chin in hand, attentively listening to the terms of the treaty as explained by another Black Carib who ostensibly acts as a translator. He leads the dark-skinned group, their nearly naked, muscled black bodies contrasting sharply with those of the British officials whose pale-faced, white-coiffed figures are outfitted from head to toe in pristine white uniforms topped by bright red coats with shiny gold buttons. Contemporary accounts describe Chatoyer and his brother du Vallé (also called Duvalle or Du Valle) as ‘well dressed’ and even refer to the latter as ‘the founder of civilization among’ his people.8 Therefore, the visual contrast achieved by the comparison of bare black bodies and clothed white ones must be regarded as a deliberate move by Brunias meant to highlight the Black Caribs as savages next to the refined image of the civilised British soldiers, one of whom is pictured conspicuously reading from the treaty document in an action that further underscores his civility.9 Brunias’s composition effects a similar contrast through the juxtaposition of the Black Caribs standing against a setting of uncultivated, undeveloped Vincentian wilderness with the placement of the British representatives against a background of finely constructed tents that portend the establishment of a colonial settlement. The sharp division of the canvas into two distinct sides – black and white, savage and civilised – when read from left to right, creates a narrative of colonial ‘progress’.

Brunias’s use of contrasts in this painting recalls Benjamin West’s famous work William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians (fig. 7), an image with which the artist might have been familiar.10 West’s painting employs similar compositional devices regarding the underscoring of contrasts and division of space, juxtaposing a gathering of gaily garbed and elaborately ornamented Delawares with a sober and drably dressed Quaker delegation led by Penn, and allocating two-thirds of the canvas to a clearly illuminated, burgeoning British colonial settlement, while relegating the Indian village to the shadowy margin of the picture. Moreover, like West, who fails to meaningfully distinguish the leader of the band of anonymous Delawares with whom Penn negotiates, Brunias does little to signify Chatoyer’s considerable status. His image of the leader certainly bears none of the hallmarks of a portrait, depicting the Black Carib hero as just another dark-skinned man in a loincloth. Stephanie Pratt astutely observes that, by the eighteenth century, British dealings with indigenous peoples had provided them with a knowledge of Indian culture that offered artists a number of modes of visual representation beyond the hackneyed ‘noble savage’ (or, in the case of the Black Caribs, ‘ignoble savage’). The fact that Brunias does so little to distinguish Chatoyer’s status among the Black Caribs is significant given the range of representations of indigenous leaders, particularly portraits, in eighteenth-century British art and visual culture. 11

6 Agostino Brunias, Treaty between the British and the Black Caribs, oil on canvas, 56 x 61 cm

Although some historians argue that the conclusion of the First Carib War actually amounted to a stalemate, Brunias clearly documents it as a moment of surrender, with Chatoyer considering the terms of his people’s submission. Interestingly, although Brunias’s painting almost certainly represents the Black Caribs, who were far from ‘pacified’ during the late 1700s, the image has conventionally been known as Pacification with the Maroon Negroes, the misleading title under which it appeared in the Edwards book, where it was ostensibly meant to represent a coming to terms between the British colonial government and the Jamaican maroons. As this chapter will illuminate, however, it is no coincidence that within a few years of this work’s creation, the so-called ‘Black’ Caribs of St Vincent, as rendered by Brunias, would be mistaken for Africans and Afro-Creoles eluding bondage.

7 Benjamin West, Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, 1771–72, oil on canvas, 191.8 x 273.7 cm

Setting the stage for a drama of division: a brief history of colonial St Vincent

A complicated and contentious history, particularly centred on the beginning of the British settlement of St Vincent in 1765 and the subsequent wars between the Caribs and the British that followed, informs an understanding of Agostino Brunias’s paintings of Carib groups.12 According to popular mythology, Columbus landed at St Vincent on 22 January 1498 and named the island in honour of the feast day of Saint Vincent of Saragossa; however, the explorer is known to have been in Spain at that time, and, in fact, no evidence exists to suggest that he ever visited the island.13 Before the eighteenth century, St Vincent was primarily occupied by a series of indigenous American groups including the Ciboney and, later, the Carib, who migrated from South America and also intermarried with Africans who, whether by providential shipwreck or self-determined escape, had eluded the yoke of European enslavement.

The Caribs generally resisted European attempts to settle the island – which they called Hairouna, or ‘home of the blessed’ – and consistently thwarted the colonisation efforts of the British, Dutch, and French. However, they eventually allowed limited settlement of the western part of the island by the French, probably as a defensive move against more aggressive British attempts at colonisation, and by 1719 some French settlers had begun small-scale cultivation of crops such as coffee, indigo, tobacco, and sugar.14 In 1748 Britain and France agreed to consider St Vincent as outside the reach of either nation’s imperial aspirations, excluding the island from the list of potential spoils in their colonial contest.15 The territory was thus regarded as neutral and ‘effectively in the possession of the Caribs’.16 Upon the conclusion of the Seven Years War, however, the British, empowered by their victory, abandoned this policy. Turning an imperial eye towards the island, they saw new possibilities for colonial expansion in St Vincent and dispatched commissioners to survey the area and divide it into plantations for sale.

However, the British colonial project in St Vincent encountered a substantial obstacle to its success: the Carib people in general and the so-called Black Caribs in particular. As early as 1730, census reports recorded the population regarded as ‘Negro’ as around 6,000 while the Carib population was said to number 4,000 (no estimates were given for the white or mixed-race population), data that indicates both the significant presence of people of African descent on the island and a tendency to regard them as separate from the Carib population in the European mind.17 According to Peter Hulme, from 1770 onwards British planters’ accounts consistently divided the Carib population into two supposedly discrete groups, Red and Black.18 Colonial settlers and officials described the western half of the island as inhabited by a small population of Red Caribs who enjoyed the protection of French colonists, while the eastward part of St Vincent, containing the most fertile lands coveted by the British, was reportedly occupied by a considerably larger number of Black Caribs.19 While different sources offered slightly varying accounts of the so-called Black Caribs’ origins, the consensus held that during the midseventeenth century a ship carrying Africans bound for New World slavery had been wrecked near the coast of St Vincent and its human cargo was taken in – and, in some accounts, temporarily enslaved – by the Red Caribs with whom they subsequently mixed.20 The merger of this group with existing colonies of maroons who sought refuge from enslavement in St Vincent’s mountainous terrain is also a standard part of this narrative.21

Relying particularly on the views expressed by Brunias’s principal patron, Sir William Young, as recorded in An Account of the Black Charaibs in the Island of St. Vincent’s (1795), this chapter considers the extent to which Brunias’s Carib pictures provided a visual narrative to reinforce the insistent – and, I argue, largely artificial – distinction between Red and Black Caribs made by British colonialists in the Lesser Antilles.22 This is not to deny the existence of significant phenotypic diversity among individuals or various groups that identified as Carib, but to suggest that, to the extent that these differences may have existed, in constructing the Red and Black Caribs as unequivocally separate and distinct groups, the British imagined or, at least, exaggerated the substance and significance of those differences in ways that supported their colonial interests. In this regard, I echo and extrapolate from Peter Hulme’s contention that ‘Black’ and ‘Red’, as ‘applied to Caribs are colonizers’ terms, ideological fictions built around the unmarked centrality of imperial whiteness’.23 Specifically, I assert that by constructing them not as free and legitimate indigenes but as African imposters originally destined for Caribbean slavery, the British colonial regime marked the Black Caribs as rebels, no better than fugitive slaves, who needed to be brought back under British control.

This chapter offers a focused study of Brunias’s Carib pictures within the political and cultural context of their creation. In order to provide this crucial context, the chapter begins with an extensive discussion of the uni...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Brunias’s tarred brush, or painting Indians black: race-ing the Carib divide

- 2 Merry and contented slaves and other island myths: representing Africans and Afro-Creoles in the Anglo-American world

- 3 Brown-skinned booty, or colonising Diana: mixed-race Venuses and Vixens as the fruits of imperial enterprise

- 4 Can you find the white woman in this picture? Brunias’s ‘ladies’ of ambiguous race

- Coda – Pushing Brunias’s buttons, or rebranding the plantocracy’s painter: the afterlife of Brunias’s imagery

- Index