This is a test

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Performance and Spanish film

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Collection exploring in detail Spanish screen acting from the silent era to present.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Performance and Spanish film by Dean Allbritton, Alejandro Melero, Tom Whittaker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Acting for the camera in Spanish film magazines of the 1920s and 1930s

Eva Woods Peiró

Strolling through the pages of Spanish cinema magazines of the 1920s and 1930s, the reader tours endless photographic galleries of actors, stars and objects. Poised for consumption, these choreographed images kaleidoscopically transmit what seems to be the entirety of the cinematic apparatus (industry, image, content, stars, spectators). Portable and spreadable, film magazines succinctly rendered the act of wandering through the visual panorama of city streets lined by shop windows and signs, a practice Walter Benjamin defined as flânerie (2007: 36–7). Benjamin’s attempt to understand a new phenomenology of vision enabled by mass reproduction was premediated in the textual medium of film magazines, in particular those published after 1910 and the inception of full-length narrative film. Yet several years before Benjamin’s 1936 essay on mechanical reproduction, in magazines such as Cine Popular, Cinegramas, Fotogramas and La Pantalla, to name only a few, we find a running commentary on the same technological shifts that concerned Benjamin: the advancements of camera technology, the commodification of acting, the significance of the shift from stage to screen, the shift from recorded motion pictures as pure display to film narrative, and that from silent film technology to sound.

A survey of the content and full runs of forty film-fan magazines from 1917 to 1936 makes it evident that historicising or theorising film acting and performance by studying the film alone provides a wholly inadequate picture of the richness and diversity of the discourse that surrounded film acting. One aim of this chapter is thus to demonstrate that film magazines are essential for understanding film acting in the context of Spanish cinema. Cinema magazines provided a forum for conversation between critics, spectators and professionals about film acting. They also shaped the direction and development of acting as both industry professionals and actors themselves read these magazines and incorporated the ideas received from magazines into their works and performances. Despite their mass-culture sheen, this form of media housed some of the most avant-garde ideas about cinema. A second goal is to demonstrate, through citation of magazine text and image, how camera technology and the specific written or visual mention of the camera in discussions of acting – through photographs, advertisements and drawings – influenced how acting was discussed. Analysing discourse on acting in instances when the camera was explicitly invoked shows how subjectivity was increasingly determined by the object of the camera.

The application of systematic study of these publications reveals the extent to which awareness of the camera had already deeply penetrated how filmgoers thought and talked about acting, what they expected from it and what they projected onto it. As ‘El arte fotográfico en el cine’ notes, the camera was no longer an observer, ‘sino un intérprete más’ [but another actor] (Anon. 1934c: 25).1 Camera technology persistently appeared in advertisements, while Spanish film critics regularly mused about the secret of photogeneity, the need for actors to physically and psychologically adjust their performances to the requirements of the camera medium, or the difficulties faced by actors due to the material exigencies of the cinema studio and the rhythm of film production.

Two intercombined logics that aided in this entertaining, educative mission were the ‘magic’ of the science of the camera and the concept of fotogenia [photogénie, or the photogenic]. Magazines carried the reader beyond the immediate experience of watching a film to help spectators develop a consciousness about cinemagoing so as to mould her or him into a more discerning and active cinemagoer, one that might consider becoming a director, or even a star. Yet, as I discuss presently, many writers tried to caution star-struck fans from racing to Madrid or Barcelona’s studios. The intention of this rhetoric was to delimit the gender and racial boundaries of spectatorship. By instructing the reader how to think about acting and actors, magazine content surveilled the borders of star culture by defining who was either a floozy, an effeminate dandy, or a subject too racialised or downtrodden to be a star.

The panorama of cinema magazines

Cinema magazines manifested the power of recording technology, photographic montage and motion picture editing, which, like the cinema, captured reality and reorganised it onto a two-dimensional rectangular surface. They were an everyday visual encounter at the Spanish kiosk’s expandable display boards. Their affordability guaranteed their abundance: by 1936, fifty-eight different cinema magazines were in circulation in Spain, and several magazines offered subscriptions.2 Magazines cost between 20 to 50 centavos [cents] during the 1920s and usually 10 cents more in the 1930s, while a subscription for Arte y cinematografía, for instance, cost 10 pesetas for a year. Spectators were familiar with magazine covers’ visual messages even if they couldn’t buy or read them. Magazine images occupied the peripheral vision of the citizen spectator who subliminally stored them, and inadvertently or consciously recalled these images while watching films or doing other cinema-related activities.

Cinema magazines both educated and entertained the reader-spectator. Magazines seduced readers through their sheer variety of content on every facet of the cinema industry and its dream-machine: overviews of national cinemas, genres, biographies, interviews and confessions of not only stars but also directors, cameramen, costume or make-up designers; opinion columns; fashion and make-up columns, debates about the direction of the Spanish cinema industry or the transition to sound; interactive content such as contests; and, of course, plenty of ads. Skilled male and female writers directly and affectionately addressed a male and female readership, pulling them into this dual-focused goal of leisure and learning, while serialisation lured readers into buying the next issue, and seduced them with promises of upcoming features and ‘to-be-continued’ cliffhangers.

Conveying such teeming diversity here is impossible given the limits of space, but even a sampling of the variety that foregrounds the camera reveals the importance of this technology to discourse on acting. For example, at some point during their run, several magazines featured a history of early cinema and moving camera technology spread out over several issues. Fotogramas offered the multi-page spread ‘Treinta años de cinematógrafo: Conmemoración de la primera representación pública’/‘Thirty Years of Film: Anniversary of the First Public Screening’, which discussed technologies such as the praxinoscope and the mutoscope accompanied by several photographs (Anon. 1926: 47–8).3 Many offered news about developments in camera technology such as an article in Cinegramas on the cámara tomavistas [cine camera], ‘El arte fotográfico en el cine: La Naturaleza, como escenario auxiliar incomparable de la cámara tomavistas’/‘Photographic Art in the Cinema: Nature as the Unparalleled Setting for the Cine Camera’ (Anon. 1934e: 5). Even the idea of ‘news’ was merged with that of the camera. A regular news column in Cinegramas, ‘Instantáneas’/‘Snapshot’, played on the instant snapshot and news ‘flashes’, but also included news pieces about anything remotely associated with photography. For instance, we learn from a 1934 issue that Claudette Colbert ‘jamás tuvo la intención de ser actriz … Como pasatiempo le gusta tomar instantáneas de gente desconocida, y a veces ella misma desarrolla los negativos’ [never had any intention of becoming an actress … [and that] for a hobby she likes to take instant snapshots of people she doesn’t know, and sometimes she develops the films herself] (Anon. 1934h: 40).

Through the camera, advertising occupied a fine line between educating and entertaining, or attracting product consumption. As a central feature of the magazine’s visual education, camera ads were not relegated to trade magazines but rather populated fan magazines as much as other products. Also frequently featured was equipment related to the camera: Erneman projectors, Ray studio lighting, Brifco film stock, film labs like Castelló y Donoso, and movie studios such as Estudios Ballesteros, CEA, Roptence or Silver Star Films, to name only a few. Doubling as ads and entertainment, sometimes articles featured ‘tours’ of Spanish movie studios.4 One possible explanation for this practice lies in what we could oftentimes call a dual-gender focus on advertising in Spanish cinema magazines. Differently from the US film magazines of the period, the magazines studied here interpellated both genders by including male and female cosmetic products (creams, girdles, hair removal products, soap), comestibles (biscuits, alcohol) and appliances (Edison and Philips radios, Citroen cars, tyres, sewing machines and refrigerators).5

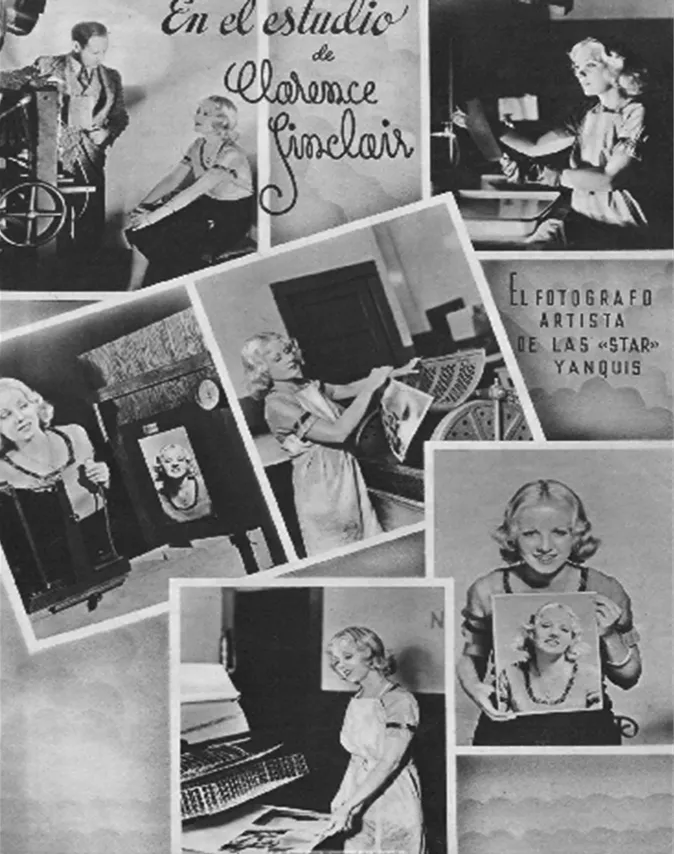

Stars and cameras: becoming and policing

The promotion of stars was enmeshed with visual and textual citations of the camera. The reliance on stars for attracting and sustaining spectatorship was clear: virtually all cinema magazines I surveyed featured a star or a popular actor on their cover.6 This dominance of star photography on the most prominent page reinforced the fusion of the star-actor with the camera object. Like Claudette Colbert in ‘Instantáneas’, stars were imagined in their interactions with cameras even when an article was not explicitly about stars. In the exposé ‘En el estudio de Clarence Sinclair: El fotógrafo artista de las “star” yanquis’/‘At Clarence Sinclair’s Studio: The Photographer of the American Stars’, we see a montage of six photos, most likely by Clarence Sinclair (Figure 1). Leaning against photo developing equipment, Sinclair stands over a pretty blonde model, as if giving her feedback before or after a pose. The remaining five photos show this same model-actress performing the steps involved in photochemical processing. In the last photo she holds up a photo of herself, in the pose she had just performed. The reader’s delight comes from the neatly portrayed ideas that the camera produces stars, but a star also gives rise to the machine, and that the innards of the industry might be run by workers who look as lovely as this gal. As photography had proved the presence of a real object, the beautiful woman was a fact, but the cleverness of it all was still magical. The technical process could therefore be exposed while piquing desire for the wondrous (Anon. 1934f: 42).

Figure 1En el estudio de Clarence Sinclair: El fotógrafo artista de las “star” yanquis’. Cinegramas, 4, 30 September 1942, p. 42.

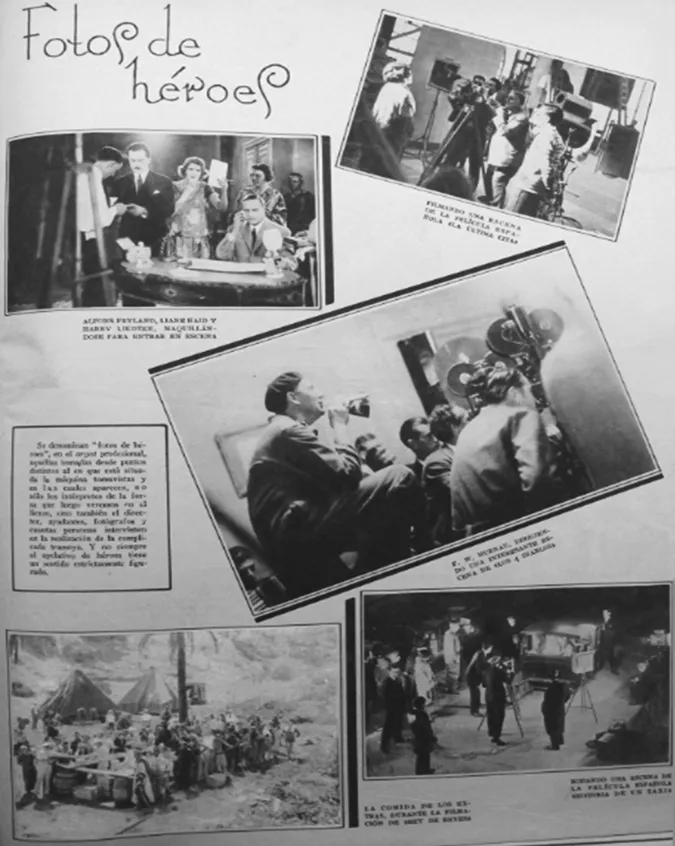

Although a reader had never been in a film studio or seen a movie camera up close, an ad or an article and its photos could help her or him imagine these spaces and objects. Photographs of rehearsals and shoots were the essence of the ‘behind-the-scenes’ view. These shots were so popular in magazines that they became self-referential, a genre in their own right: ‘fotos de héroes’ [hero photos] (Figure 2). According to a photo caption of a montage of five such photos in La Pantalla,

Se denominan ‘fotos de heroes,’ en el argot professional, aquéllas tomadas desde puntos distintos en que está situada la máquina tomavistas y en las cuales aparecen, no solo los intérpretes de la farsa que luego veremos en el lienzo, sino también el director, ayudantes, fotógrafos y cuantas personas intervienen en la realización de la complicada tramoya’. [Hero photos, denominated as such in professional argot, are those shots taken from different points in which the cine camera is situated and in which there not only appear the actors of the farce that we will later see on the screen, but also the director, the assistants, cameramen and all those who intervene in the realisation of the complicated stage machinery.] (Anon. 1928: 924)

Figure 2‘Fotos de héroes’, La Pantalla, 55, 1929, p. 924.

Fotos de héroes summarised in one image the inside scoop. At the same time that they ‘scientifically’ dissected cinema, they indulged readers’ imagination in the magical feats of the camera. As Alice Maurice argues, in the context of many US silent films, the scientific prowess of ‘the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: approaching performance in Spanish film

- 1 Acting for the camera in Spanish film magazines of the 1920s and 1930s

- 2 Performance and gesture as crisis in La aldea maldita/The Cursed Village (Florián Rey, 1930)

- 3 Exaggeration and nation: the politics of performance in the Spanish sophisticated comedy of the 1940s

- 4 The voice of comedy: Gracita Morales

- 5 The sounds of José Luis López Vázquez: vocal performance, gesture and technology in Spanish film

- 6 The influence of Argentinian acting schools in Spain from the 1980s

- 7 Askance, athwart, aside: the queer plays of actors, auteurs and machines

- 8 The future of nostalgia: revindicating Spanish actors and acting in and through Cine de barrio

- 9 Performing the nation: mannerism and mourning in Spanish heritage cinema

- 10 Performing sex in Spanish erotic films of the 1980s

- 11 Becoming Mario: performance and persona adaptation in Mario Casas’s career

- 12 Performing fatness: oversized male bodies in recent Spanish cinema

- 13 Disabling Bardem’s body: the performance of disability and illness

- 14 Body doubles: the performance of Basqueness by Carmelo Gómez and Silvia Munt

- 15 Los amantes pasajeros/I’m So Excited! (2013): ‘performing’ la crisis

- Index