This is a test

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A collection of essays by established feminist and cultural critics interested in experimenting with new styles of expression.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Writing otherwise by Jackie Stacey, Janet Wolff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Russian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

II

Displacements

Atlantic moves

Janet Wolff

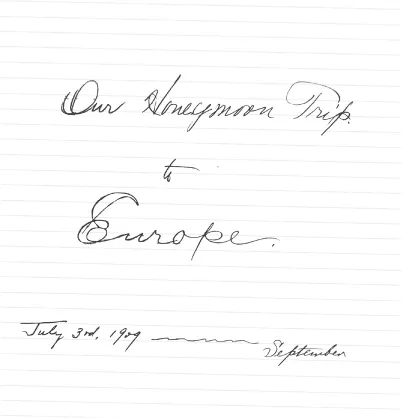

We have traveled quite a distance, but we never had so poor a day of it as to-day. It was the only day of our trip that we didn’t enjoy the traveling. We got on a train at 4 p.m. and were supposed to reach Manchester at 8. Twice we had to change trains and each time you got to go and look up your train and see that it’s taken out. It’s a nuisance. To make matters worse, we had nothing to eat all day but a couple of ham sandwiches and some cold chicken which though historic (for it was brought up probably in the time of Shakespeare), was not very digestible. Of course the train was late and we got into Manchester at 9.15. Luckily, Maurice, knowing how punctual English trains are, did not get discouraged, and waited for us. It was a relief to get settled down at last, and an indescribable pleasure to come amongst friends after six weeks of hotel life. And here we saw friends I hadn’t seen for nineteen years and most of whom I couldn’t even recall. It was a reunion indeed and everyone was happy that we were able to meet. We remained at the home of our cousin, Israel, and he and his wife were very nice to us and went out of the way to accom[m]odate us. It was a relief to feel among your own, with your own flesh and blood and to know that people were nice to you not because they hoped or worked for a tip, but because they loved you and were a part of you. We staid up late to-night till 1 a.m. and some of the other cousins came over, Ely and his wife and Dora and we talked of old times and present times and future times and when we retired, a sleep of rest and contentment enveloped us.

(Travel diary of Henry Norr, 1909)

Henry Norr, born in St Petersburg in 1880, moved to the United States with his family (parents and two sisters) in about 1891. His father, Jacob Norr, was a tailor, who also established himself in the real estate business in New York. His mother, Dina, was a wig-maker for orthodox Jewish women. Henry went to City College, became a secondary-school teacher and, in 1926, took the post of principal of Evander Childs High School in the Bronx. His obituary in The New York Times in 1934, on his early death of a heart attack at the age of 53, quotes the new City Superintendent of Schools, Harold G. Campbell, as saying that ‘Mr. Norr was one of the best high school principals in the City of New York. In spite of an innate modesty and a retiring disposition, he was one of the most forceful characters in secondary education… His going leaves a great void in our secondary schools which it will be difficult to fill’. (Mr Campbell also offers another compliment, which would today perhaps have been worded a little differently: ‘He had a genius for handling boys and girls’.)

In 1909, Henry married Minnie Gold. The travel diary is the detailed handwritten account of their honeymoon trip in Europe, in the course of which the couple visited the English branch of the Norr family (whose spelling of the name was ‘Noar’). Jacob’s oldest brother, Joseph, had emigrated to England in 1886, and worked as a tailor in Manchester. Israel, Eli, Dora and Maurice – mentioned in Henry’s diary – were four of Joseph’s seven children. Maurice Noar was my maternal grandfather. He came to England as an infant, and would have been about twenty-four when he met his American cousin at the railway station in 1909.

It was Henry’s son, David Norr, who showed me the diary in December 2003, at his house in Scarsdale, New York. I took the train from New York on a very snowy day, and he met me at the station to take me for lunch at home with his wife, Carol. It snowed all afternoon, so much that we weren’t sure if I would be able to get a taxi back to the station that day. I had never met David Norr before. In fact, I had never heard of him until a couple of months earlier, when a cousin of my mother’s in Manchester, who had kept in touch with the American relatives, urged me to see him while I was still living in New York. He was eighty years old at the time of my visit – still active as a financial analyst, and keen to discuss family history with me. Later he sent me photocopies of the ‘Manchester’ pages of his father’s diary.

August 17th

The day is a dull and threatening one and the atmosphere is murky. But here in Manchester it is considered a fair day indeed, for rain and fog is the average lot of Manchestrians.

The city’s main industry is cotton goods manufacturing and there are a great many mills here. The smoke of the chimneys together with the usual foggy atmosphere, casts a sort of mist about the city that blackens all the buildings, and the black and gray stone of London here become almost coal-black.

We are barely into the Manchester visit, and I am already getting defensive, and a bit irritated with the tone. Of course he is right, both about the weather and about the colour of Manchester buildings (though not about the inhabitants, who are of course Mancunians). Before the Clean Air Act of 1956, and the decline of industry, the pale stone was usually black with soot, and the air was often filthy. We sometimes had to walk home from school wearing smog masks. Still, the tone seems, to me, a bit condescending. It continues:

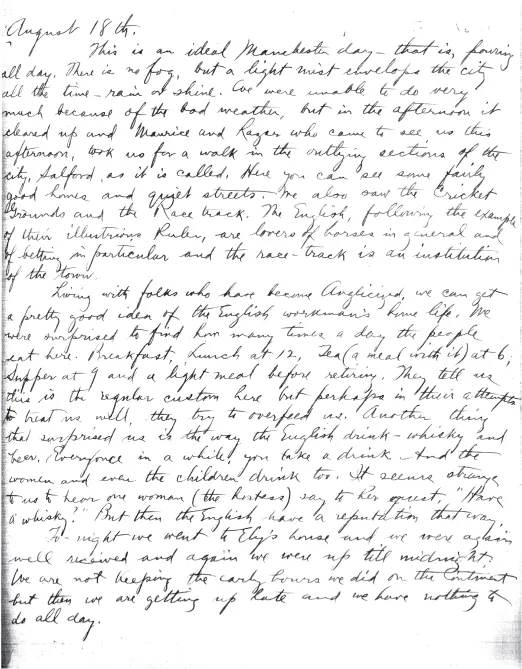

August 18th

This is an ideal Manchester day – that is, pouring all day.

Then there are the English eating – and drinking – habits to comment on, only partly affectionately:

Living with folks who have become Anglicized, we can get a pretty good idea of the English workman’s home life. We were surprised to find how many times a day the people eat here. Breakfast, Lunch at 12, Tea (a meal with it) at 6, Supper at 9 and a light meal before retiring. They tell us this is the regular custom here but perhaps in their attempts to treat us well, they try to overfeed us. Another thing that surprised me is the way the English drink – whisky and beer. Every once in a while, you take a drink. And the women and even the children drink too. It seems strange to hear one woman (the hostess) say to her guest, ‘Have a whisky?’. But then the English have a reputation that way.

There is a rather poignant counter to this expression of American puritanism. Here is the point of view of the English Noars, from a family history compiled in 1998, recalling Henry Norr’s honeymoon trip:

He got the English cousins quite wrong as a bunch of drunkards, because wherever he visited, out came the Whisky bottle: little did he realize that it took a visit such as theirs before strong drink was taken.

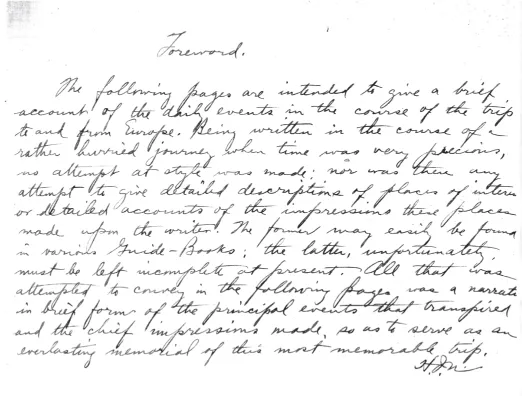

Still, apart from a few more such asides, this is a wonderful document, with descriptions of family members, accounts of walks round the city, a trip to the Manchester Hippodrome, a visit to Bolton to see another cousin. The handwriting is beautiful, and the thoughts of a young visitor to Europe just over a hundred years ago never less than fascinating to read. In particular, it seemed important for once to be somehow in touch with my mother’s family history. For a number of years it had been my father’s life, in Germany in the 1930s and as a refugee in England, interned for a year in the Isle of Man, that had preoccupied me. On my mother’s side, the dramas of persecution and flight were less immediate, a pre-history to her own life and experience. Even her parents were small children when anti-semitic pogroms in eastern Europe obliged the families to travel west. Now I began to see both how interesting these lives had been and how the memory of forced exile persists through the generations. Although I have some resistance to the notion of ‘second generation’ Holocaust survivors (that is their children, assumed to inherit their trauma at one remove), I am entirely persuaded by Marianne Hirsch’s notion of ‘postmemory’.

Postmemory characterizes the experience of those who grow up dominated by narratives that preceded their birth, whose own belated stories are evacuated by the stories of the previous generation shaped by traumatic events that can be neither understood nor recreated.1

I have come to understand that this inheritance can have a longer trajectory, across more than one generation. Mary Cappello has written movingly about the ‘ways that we inherit the pain or deformation caused by the material or laboring conditions of our forbears’, linking her own chest pains to those of both her father and her grandfather.2 In her case, the inherited injury – actual and psychic – related to the poverty and shame of earlier generations. As I read about Ashkenazi Jews in north Manchester in the twentieth century, and recalled visiting my own relatives as a child, I began to grasp the idea of the transmission of fear, caution and suspicion, even decades after the event. The children of those immigrants from eastern Europe retained, and in turn passed on to their own children, the unarticulated but painful recollection of persecution. What Anne Karpf has referred to as ‘the war after’ is one fought by Jews of east European origins as well as refugees from Nazism.3 My mother as well as my father.

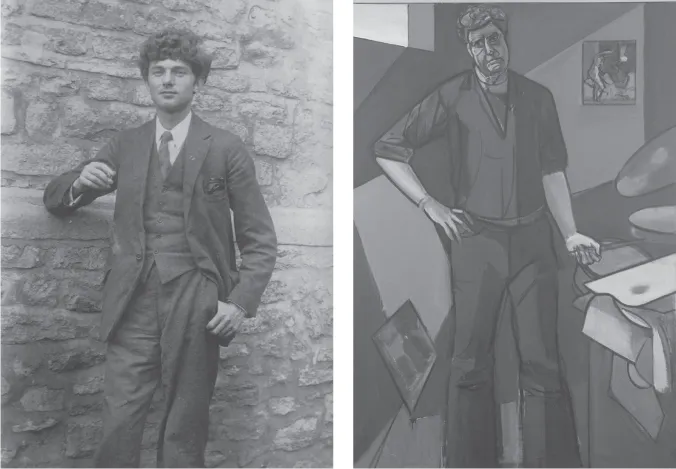

Left: Mark Gertler, photographed by Lady Ottoline Morrell

Right: Leland Bell: Standing self portrait

Right: Leland Bell: Standing self portrait

It was also from David Norr that I learned that one of the American cousins – Harris Norr, also known as Swifty Morgan – who made a living as a professional card player on transatlantic liners, may have been the model for Damon Runyon’s character, the ‘lemon drop kid’. Also cause for reflection was the fact that, while I had been developing my personal and academic interest in the English-Jewish artist Mark Gertler, largely on the grounds that he may have been a distant relative of my maternal grandmother – Rebecca Gertler, wife of Maurice Noar – I now discovered I had a bona fide, rather famous artist cousin in the United States. This was Leland Bell, nephew of Harris Norr and second cousin of Henry Norr. All of this has been especially interesting to me recently, since my return to England after eighteen years in the United States, and as I continue to rethink (and rewrite) my own stories about the two countries.

It seems to me now to be so transparent, the rewriting of narratives at different stages of life. Today, I seem inclined to take England’s side against any criticism (especially, perhaps, by an American). But not so long ago I put quite a bit of energy into my own demonising of England – the other side of my idealising of ‘America’, perhaps. In 1976, my father wrote a short memoir of his own, reflecting on his experiences in Germany in the 1930s, recording the increasing processes of Aryanisation that he confronted in his work as a chemist, and the growing isolation in his everyday life. Towards the end, he expresses his gratitude to Britain:

It is too often forgotten, how much we owe the British Government of the day, who, with the help of Jewish and other British organisations, in which people like Eleanor Rathbone played a leading part, saved tens of thousands of Nazi victims, when all the other countries refused to do anything.

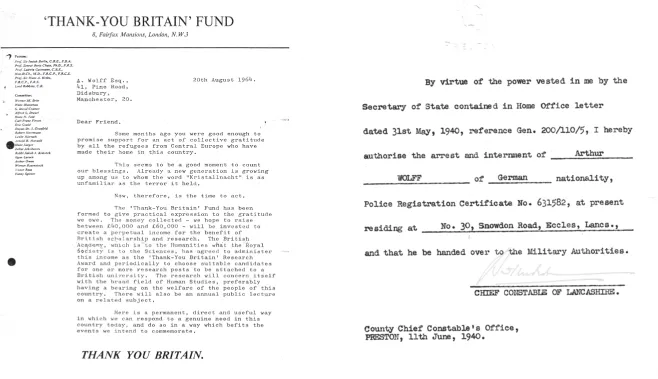

I was glad, therefore, when a few years ago some of those who managed to start a new and successful life here launched a ‘Thank-You-Britain Fund’, which soon raised about fifty thousand pounds for a scholarship now administered by the British Academy. Its income is used to finance University scholarships in the field of Human Studies, particularly the welfare of people of this country.

Ten years later, though I don’t think I ever discussed this with him, I was immersing myself in another point of view, reading the growing literature on England’s own history of anti-semitism and following David Cesarani’s account of Britain’s rather more compromised activities in the mid-twentieth century (including the post-war acceptance of Nazi war criminals into the country).4 I learned that the internment of aliens in 1940 (about which my father, who spent over a year in an internment camp, had nothing critical to say) was in fact an outrage.5

I read (and also wrote) about the earlier resistance to Jewish immigration to Bri...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Writing otherwise

- Affects

- Displacements

- Poetics

- Image credits