![]()

1

Material backgrounds: print, dissent, and the social society

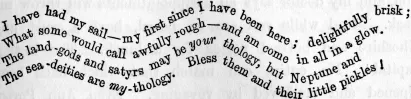

How did Hood become a writer and illustrator whose every utterance is liable to play? Answering this question means looking afresh at Hood's background and the route he followed into the literary profession. The first two chapters of this book are particularly concerned with three aspects of Hood's upbringing and apprenticeship: his early exposure to the burgeoning marketplace of printed products, the culture of dissent that shaped his family life and schooling, and the social and political community within which he produced his first works. Unusually amongst authors, Hood was born into the publishing industry. He grew up in the midst of typefaces, burins, books and broadsides, political cartoons and advertisements. Trained as an engraver, his intimate relationship with words as signs is distinctive. In a letter of May 18331 Hood writes to fellow-engraver John Wright about a seaside holiday that he is enjoying (Fig. 1.1).

Exuberantly breaking the formal rule of line, the sentences on the page have become the waves that they describe, an ideogram as well as a description. Individual words are also in flux: abstract mythology becomes personal my-thology, as Neptune materializes in Ramsgate. Hood's approach to writing is energized by constant awareness that language is a shifting assemblage of unreliable characters – as he puts it in his late poem, ‘A Tale of a Trumpet’, where a deaf old lady is seduced by the offer of a magical hearing aid: ‘Filthy conjunctions, and dissolute Nouns, / And Particles pick'd from the the Kennels of towns, / With Irregular Verbs for irregular jobs, / Chiefly active in rows and mobs, / Picking Possessive Pronouns' fobs’.2 To Hood, words are like people, with a lively tendency to mingle and misbehave, so that meaning is inherently multiple, constructed, an effect of social reading where intention and reception may be hilariously at odds. In the preface to his German travelogue Up the Rhine (1839) he tells the story of ‘a plain Manufacturer of Roman Cement, in the Greenwich road’, who ‘was once turned by a cramped showboard’ into a ‘MANUFACTURER of ROMANCEMENT’ and quips that ‘a Tour up the Rhine has generally been expected to convert an author into a dealer in the same commodity’, but his own account will be heretically prosaic.3 Roman cement is a type of cement made of lime, water, and sand, which was patented at the turn of the nineteenth century and was used chiefly as a render for the outside walls of buildings. Hood, with his quick eye for public signs and advertisements, instantly notes unintended coalescence between the most prosaic of building materials and the most ethereal of literary fabrics. His upbringing in a world of print makes Hood hyper-aware of the porousness of language and its susceptibility to plural readings within the marketplace of competing representations. This awareness informs a remarkably democratic view of literature as a commodity: purveyors of render and renderers of narrative turn out to be working the same stall; the ‘Literary and Literal’ (the title of one of Hood's poems) can never be kept apart, when a cramped showboard will always suggest their fundamental identity.

Hood's play with the idea of ‘Romancement’ as a commodity is also a direct consequence of the steam-driven literary landscape he inhabits. As the preface to Up the Rhine continues:

Since Byron and the Dampschiff, there has been quite enough of vapouring, in more senses that one, on the blue and castled river, and the echoing nymph of the Lurley must be quite weary of repeating such bouts rimés as – the Rhine and land of the vine – the Rhine and vastly fine – the Rhine and very divine. As for the romantic, The Age of Chivalry is Burked by Time, and as difficult of revival in Germany as in Scotland. A modern steamboat associates as awkwardly with a feudal ruin, as a mob of umbrellas with an Eglintoun ‘plump of spears.’4

Hood's attraction to the prosaic, the material, and the humorous, and his frequent exposure of the tension between them and ‘poetic’ sensibility, reflect his consciousness of the irony that, as the ‘romantic’ has become widely prized and imitated, it has contributed to fuelling commercial developments at odds with its ostensible vision. There is a direct connection between lyrical vapouring and the tourist steamboat retracing the journey described in the third canto of Childe Harold's Pilgrimage. Industrialization and poetry, apparent enemies, are actually sleeping partners. The years following the Napoleonic wars saw a marked rise in the number of works being published.5 New technologies brought larger print runs and a wider range of publications with new kinds of format, illustration, binding. The status of literature as an industrial product had never been so obvious. The commercial reach of the print trade and of the literary lion were greater than ever before. Yet the growing ubiquity of the printed word and of authorship created a situation where different kinds, forms, and genres of text were no longer securely separable and the increasing prominence of competing indexes whereby a text might hold value (as autograph, as advertisement, as gift, as aesthetic object) threatened literary hierarchies. In one sense Hood is a typical writer of the 1820s and 1830s. As Richard Cronin remarks in Romantic Victorians, these decades are marked by authors' increasingly open engagement with the commodified status of their own writing: in Silver Fork novels, in Newgate novels, in journalism.6 But Hood is atypical in that as a poet, raised and supremely at home in the new print culture, he brings its fortuitous mixing and creative exploitation of textual materiality into poetry itself. His play revels in the susceptibility of words to be recomposed, as they might be by a proofreader or a typesetter, but also in shop fronts, newspapers, letters, as sites of competition and conversation between the ‘literary’ and the ‘literal’.

A world of print

Hood was born the second son of Thomas Hood, a partner in the bookselling and publishing firm Vernor and Hood (later Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe). As he joked in his ‘Reminiscences’, he had ‘ink in his blood’. His maternal grandfather, James Sands, was an engraver, as was his uncle Robert Sands, and Hood would as a teenager go through the apprenticeship that permitted him to work as an engraver within the print industry. This training enabled him to illustrate his writing with comic woodcuts, making his Comic Annuals, like Edward Lear's later books of nonsense, wonderfully composite texts in which word and image have an unusually fluid relationship. Hood learned, minutely, to copy backwards, in a format where letters are just one form of malleable sign: skills that underwrite his gift for parody and his sensitivity to the ‘doodle’ and ‘babble’ qualities of words, their susceptibility to morph into visual and aural relations. The premises of Vernor and Hood at 31 The Poultry were centrally located in the heart of the City, amidst a panoply of trade, close by the Guildhall and the Exchange. They published poetry, most notably the works of the shoemaker-poet Robert Bloomfield, but also plays, some fiction, travelogues, atlases, a variety of religious, educational, and discursive works, and periodicals – the Ladies Monthly Museum and the Monthly Mirror – a multiplicity of textual forms mirrored in Hood's own writing. Moreover, Hood and one of the new technologies that would transform the print industry arrived almost simultaneously: Vernor and Hood were reputedly responsible in 1804 for the second book ever stereotyped in England.7 His quotidian experience of the practical logistics of book and periodical manufacture infuses Hood's understanding of the page as a microcosm of the marketplace.

From the beginning of his career Hood's eye is joyfully alive to the variety of forms that print can take. In his 1825 engraving The Progress of Cant, Hood depicts the London street as a crowded mêlée of competing texts. There are sixty people in this imaginative scene, but they are far outnumbered by the printed materials that surround them, primarily the banners individuals carry to indicate their partisanship of particular causes, but also the books, pamphlets, and other papers they trample underfoot; the boards and flags that identify the buildings underneath which they are passing; and the multiple layers of posters and bills attached to walls and fences. Hood does not allow any conventional hierarchy or fundamental distinction between these different kinds of text. Indeed the books scattered on the ground are lowest in the visual field, whereas the signs that hang from the walls and buildings are highest. A Meeting of Operatives, an entertainment at Drury Lane, Patent Pumps and a Prayer Meeting compete equally on a wall for the attention of passers-by, much as people in the crowd compete for an audience on an equal footing. The purveyor of concrete goods and services (a bank) and of spiritual salvation (Whitfield and Wesley) promote their goods in a proximity that generates a pun on ‘saving’. Everyone is advertising something, and the effect is not only to erode difference between different textual media, but also between material and abstract commodities. People and signs are identified with one another, as almost all persons bear a legend, the text carried on a banner or an apron, ...